– by Albert Lowe, Archivist for CHSSC’s Duty and Honor Collection

Dr. Julius Sue (center with tie) with medical group in China. Julius Sue received his MD from the University of Oregon in 1941. He was a major with the 14th Air Service Group in India and China. Later, Sue was nicknamed “Godfather of Chinatown” for his leadership at the Chinatown French Hospital. Sue also served as vice president of C.A.C.A. and commander of American Legion Post 628.

Photo courtesy of Duty and Honor.

Bottom right is Dr. Tim K. Siu, who was a pharmacist mate for the “USNH” – United States Navy Hospital. Tim was an anesthesiologist and professor emeritus of the USC Medical School. Some of his volunteer activities included Rotary International, American Red Cross, CSULA Advisory Board, and West San Gabriel Valley YMCA. He received CHSSC’s Golden Spike Award in 2012 for his community leadership.

Photo courtesy of Duty and Honor.

Surprisingly, I had never set foot in the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California (CHSSC) Bernard Street houses until they interviewed me for the Duty and Honor Collection archivist position in August of 2018. I’m not sure why it took me so long to ever visit. I studied Asian American studies at Cal. I was a member of San Francisco’s Chinese Historical Society in the mid-1990s. In my spare time, I visit Chinese American sites in the state—from Locke to Coloma. When I was a Master of Library and Information Science (MLIS) student, I already knew of Marjorie Lee whom I interviewed for a paper in 2010. Marji was the principal investigator of CHSSC’s Duty and Honor project in the 1990s. She led a team of dedicated volunteers that eventually published the Duty and Honor book (CHSSC, 1998). Yet, for some reason, I never visited the CHSSC until this job interview.

The CHSSC archivist job posting’s journey from CHSSC Vice President Linda Bentz to my inbox via five forwards was only about seventeen hours. The Society had received a generous donation from Friends of the Chinatown Library to properly organize the Duty and Honor Collection. This Gum Saan Journal is a resulting tribute to our World War II heroes from this digitizing project.

On my second time ever at the CHSSC and first day as the project archivist, I eagerly reviewed the Duty and Honor Collection contents. I looked over the collection and found a plethora of Chinese American historical documents in 13 banker boxes—photos, slides, audio interviews, military records and other associated materials.

My interest in Duty and Honor was fated as my family has a close relationship with World War II. My third generation father, Wayman Lowe; his twin brother, Stanley Lowe; and his older sister, Gracina Lowe, were all in the armed forces during WWII. Many of their cousins also served during the war. When I reached the sixth or seventh box of the collection, I found five binders with Polaroid pictures taken of the veterans in 1995–97. While flipping through the pages, there was Uncle Raymond’s photo on the first page of the third binder. Raymond Lee was my dad’s first cousin and served in the navy.

World War II changed the lives of many individual Chinese Americans, and it was a watershed moment for our community. For a racial group struggling for American inclusion and burdened with the sojourner thesis, participation in WWII was an opportunity to demonstrate American identity. My dad’s WWII storytelling was focused on how he and his twin played practical jokes on his sergeant by pulling the “switch-a-roo” for extended leave, but the war had a huge impact as the G.I. Bill allowed my dad and uncle to attend U.C. Berkeley. Aunt Gracina attended a conservatory school after being part of the Coast Guard. However, my dad never took advantage of the War Brides Act of 1946. He did not marry my mother until 1965.

Seventy-five years after WWII, Chinese Americans and other Asian Americans, regardless of how long we have lived in the United States, still live with the racial ascription of perpetual foreigner. Comments like, “Wow, you speak English well,” “Where are you really from?” or my favorite, “I met a Chinese guy in Seattle; do you know him?” are all too familiar to me from forty years ago to today. At the very least, the U.S. Congress recognized

our role in WWII and signed into law The Chinese American World War II Veteran Congressional Gold Medal Act in 2018. The Act honors 20,000 Chinese Americans for their military participation in World War II. The long campaign for the passage of this act was led by the Chinese American Citizens Alliance (C.A.C.A.); it calls for the striking of one gold medal to be displayed at the Smithsonian Institute, and duplicate bronze medals for veterans or their families. After reviewing military separation papers for weeks, I easily found my father’s Army documents and applied to receive such a medal on behalf of my family.

National C.A.C.A. Advocacy Team in 2018 with 115th Congress’ S. 1050 sponsor, Senator Tammy Duckworth (D, Ill). Duckworth’s mother is a Thai-Chinese. Lt. Col. Duckworth served in the U.S. Army from 1992–2014.

Photo by C.A.C.A. Boston Lodge’s Esther Lee.

Congressional Gold Medal for Chinese Americans WWII Veterans design. Senator Tammy Duckworth (D, IL) sponsored Public Law 115-337.

Quite honestly, the six hundred or so military records of Chinese Americans in the Duty and Honor Collection are not that interesting. If you see one, there’s not that much difference from any other honorable discharge paper. After reviewing the Duty and Honor contents, I could immediately assess that the interviews and photos were the jewels of the collection. Strangely, of the forty-four interviews, one was with a fourth generation Chinese American also named Albert Lowe.

Besides both of us being fourth generation, the other Albert was born in San Diego, where my great grandfather once worked as an asparagus farmer. The veteran Albert Lowe’s parents were named Albert and Ann Lowe. I am also married, and my partner’s name is An. What type of coincidence is that? I was also happy to know that my same name comrade was a Pasadena School Board member in the 1970s, and he supported public school racial integration amidst protest. I would like to think that the Albert Lowes of the world could unite for civil rights and desegregation. My full-time day job is with the United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA)—the union representing teachers in the Los Angeles United School District (LAUSD)— and some of my primary roles are promoting workers’ rights and student justice, which includes dismantling racial segregation.

Who else was I going to unearth in this collection? Midway through finishing the discarding and rearranging, I finally decided to process the slide photos and photo reproductions. One reason why I waited to process the slides is because I needed a projector to have a better view of the one- by-one inch photos. Astoundingly, I found two slides of my aunt, Gracina Lowe, who never lived in Southern California. One of the slides show

Aunt Gracina in uniform at Golden Gate Park. I never knew Aunt Gracina because she passed away when I was two years old, but photos of her graced a number of rooms in my grandma’s house in Oakland. I knew the woman in the slide was my aunt, and sure enough, the photo registry listed my aunt’s name right there in print.

As exciting as it was to find my aunt’s photo and hypothesize how it reached the Duty and Honor Collection, the random unknown reproductions were the most fun to figure out. With a combination of the named photos from the text, the Polaroid photos of the “fifty years later,” and other known photos, I embarked on the laborious project to determine who were the younger version of the veterans in these unlabeled photos.

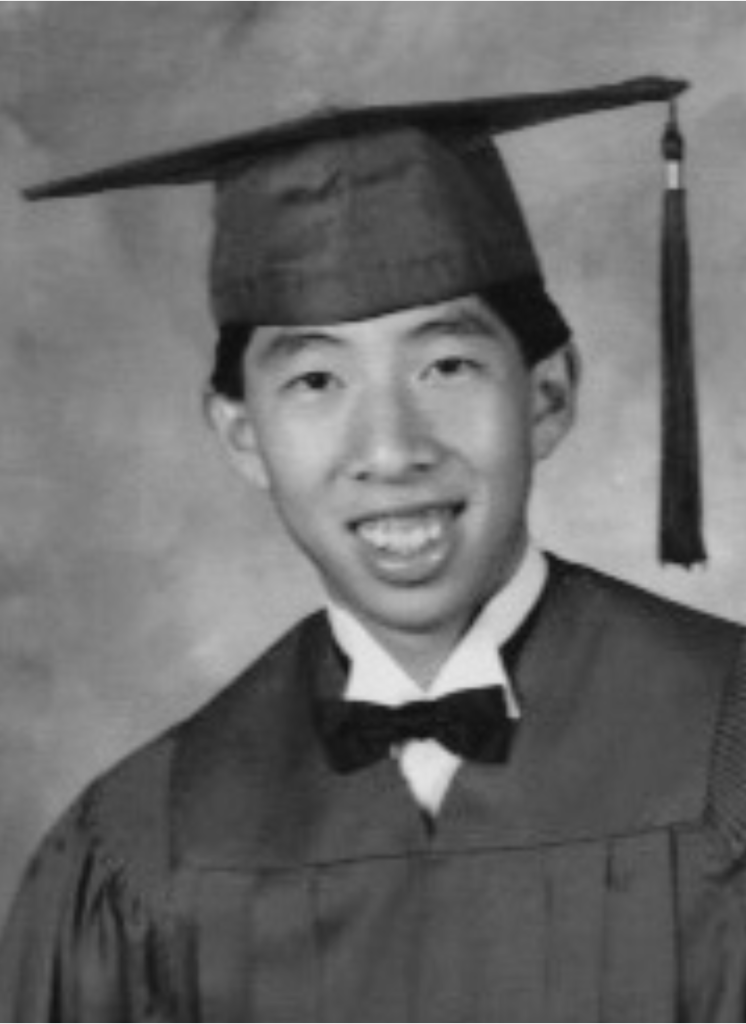

I, along with a California State University Northridge intern, Joslynn Cruz, figured out 80% of whom was in the photos, but we have a folder with the remaining 20% of “unknown veterans.” One of these “unknowns” looks like me!

Left: Albert Lowe at age 18.

Right: Photo of unidentified soldier who looks like Albert Lowe.

Photo courtesy of Duty and Honor.