– Fred Gong, Jr. (1923-2017)

Fred Gong Jr. was a recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross. He served his country in World War II with the 82nd Fighter Group, 483rd Bombardment Group, 15th Air Force between 1942 and 1945. The 483rd was stationed at Sterparone, Italy. Gong was a First Lieutenant in the Army Air Force where he served as a bombardier and a fighter-bomber. Fred had a career as a commercial artist. “Grandpa Fred” was the youth counselor at the Chinese United Methodist Church for about twenty years, and volunteered his time with the Chinatown Library and the Los Angeles City Public Library. This is from an interview with Marji Lee on 5 April 1997.

When I was a kid,1 these young Chinese American men would come visit us. Some of these young men came from California or the Midwest. A lot of these men were university students and learning to be flyers. In the city of Portland where we lived, there was a flying school on Swan Island. They advertised for young Chinese men who wanted to be part of the Chinese Air Force.2 My parents were community-involved; my father ran a grocery store, and my mother was a teacher. They were wonderful young men. I thought that when I grew up, I wanted to be one of them.

15th Air Force’s Fred Gong.

Photo courtesy of Duty and Honor

When I was a freshman at the University of Oregon, Pearl Harbor happened, and I wanted to join the military right away. My professor said, “No, go ahead and finish the year.” In those days, the War Department was slow moving. I took the examinations for the Air Force in the fall and by December, I still had not heard if I had passed. I went to my high school teacher who advised me to write to the senior senator of Oregon, Senator Charles McNary. I did write to him. Within a couple of days, I got a telegram from the senator that read, “I have phoned the War Department in Washington, and you are qualified.” Before I took the examinations, I was afraid they would find some excuse to not let me go because I’m Chinese American. After I knew I had qualified, I knew there would be no trouble after that. The next day, on 1 January 1943, I got a letter from the President of the United States that read “Greetings. You are to report to Fort Lewis.” So, I was drafted while I had Senator McNary’s telegram in my pocket.

My sergeant said I had to go through procedure. I was a draftee for several weeks at Fort Lewis in Tacoma, Washington. But then the sergeant called me in. When Fort Lewis heard from the War Department, I left immediately as the Army Air Corps needed fliers so badly. History shows that in the spring of 1943, we were losing on all fronts. I was sent to Santa Ana, California3 that night for training. I got in very late, and they gave me my cadet clothing.

In Santa Ana, I would not be called “Gong,” but referred to as “Mr. Gong.” As a cadet, we were fed well (laughs). I had three months of ground crew training. It was tough and included crawling under machine gun fire (laughs). The training included higher mathematics, rules of war, physics, weather. There were three months of pre-flight training and examinations. We had no social life; the Army was in a hurry.

Then, you had to choose between pilot training, navigation training, or bombardment. I chose bombardment because since I was a little kid, I wanted to fly the biggest bombers and drop the biggest bombs. I’m a little guy, but I wanted to do big things. Navigators spend a lot of time with maps. As a pilot, I could be assigned to Transport Command where I would just be moving freight from one place to another. It’s like being a truck driver. So I chose bombardment, and I got my wish.

Then I got transferred to Deming, New Mexico for advanced training. And if you don’t mind my saying so, I must have made good grades all throughout. Upon graduation at the end of July, I was appointed instructor in bombardment—which amazed me.

Bombers training is in two parts. The first part is focused on physics and math. It really wasn’t too useful. Training was six days a week. After three months, I had six cadets sent to me so that I could mentor them. I would fly with two cadets at a time in the day, and in the evening were these larger classes. We taught what makes an airplane fly and what makes a bomb work. We also taught larger classes about mechanics, the chemistry of the bombs, and things like that. We had to rush these guys along. My class was something like “Bomb Shackles and Fuses”—the real nitty gritty detail of the science of bombardment (laughs).

I was in Training Command for about five months in Deming, New Mexico. Then I requested a transfer to combat duty. That was common place in those days. We had joined the Air Force to fight for our country. Now we were stuck in the desert training cadets. We had to write a letter to the base commander to be transferred. He had to wait for orders from headquarters.

I didn’t want to spend the entire war in Training Command out in the desert. When you are nineteen or twenty years old, you don’t think of the danger. When I got transferred to combat duty, it was the happiest day of my life. That was my original intention.

Gong is lead bombardier on a B-17 Flying Fortress.

Photo courtesy of CHSSC

We reported to the adjutant who gave us orders to go to Rapid City. It took a couple of months before we went to Overseas Training (OT) in South Dakota. We got to fly four-engine bombers. In training, we flew twin-engine planes. I found out that I was very good at it. There were six of us on a team. They were all proud of me when I reached five miles up in the air. In training, we only go 10,000 feet up. In Overseas Training, we fly 30,000 feet up. When I hit the target squarely in the middle, a cheer went out through our plane.

My friend was also in the Air Force, but he doesn’t want to talk about his military experience; his brother was killed as a flier. He got to Europe about six months to a year before I did. At that time, the bombers did not have fighter support.4 They had to fight their way in and fight their way out. When I got there, we had fighter support. We had enough fighter planes who had the range to accompany us to the target and back. For my friend, it was a terrible experience. His older brother was a navigator.

As a soldier in combat, you learn not to make friends. They tell you that quite early. You may be having breakfast with somebody, and by noon, he may be dead. Of course, this is emotionally hard on young soldiers. We only became friends and buddies after the war was over. When my pilot called me from Pennsylvania after the war, I almost fell over. I said to him, “You made a hero out of me.” He flew the plane so steady that I couldn’t miss. A bomber is only as good as his pilot is. Imagine shooting from a moving car. You can only hit your target if your pilot or driver holds things steady. I didn’t know until our reunions after the war that my pilot had flown navigation students and also flew bombers before he was transferred to fighters. I’m a member of the 483rd Association and the 82nd Fighter Association. Most pilots wanted to be fighter pilots. It’s just sort of more fun. So he had the training and experience to hold the plane so steady. We got to fly B-17s; they are called “the Flying Fortress.”

When we were sent overseas, we didn’t know where we were going. Some people thought we’d be sent to China. That’s okay with me. We got these secret orders. The pilot was not supposed to open the secret orders until we were half way across the Atlantic Ocean. That way our families wouldn’t know. We flew at night to Algiers in North Africa to receive our next set of orders. The Germans had already been driven out of North Africa, but the community there was very poor. We were then sent to southern Italy. The African American Tuskegee Airmen were also in Italy nearby. They were not allowed to mix with us. We were racially segregated, but we knew they were very good. They were the Red Tails, and Black and Yellow Checkerboard Tails. The Germans were afraid of them. I was not segregated, and I could tell that the world was changing.

For the first few missions, I was deputy leader. Our squadron in combat had eight or nine planes. By the third or fourth mission, I was moved up to squadron leader. I was the lead bombardier. But the most important thing is that I got not a word of complaint from the other fliers. Four squadrons make a bombardment group. Later, I was leader of the entire bombardment group. It was an honor. Later, when I was transferred to fighters, I was immediately the leader of the fighter group—which was sixteen planes. We had sixteen planes stacked in formation.

I was afraid only on the first mission. You see planes in front of you exploding and going down in flames. And you see enemy fighters coming. On the second mission, I knew what to expect. Our job was to see how many chutes there were. When you get back, you knew how many fighter planes went down. We knew that in the 99th Bombardment Group, there were two planes that went down and nine parachutes. Our job was to put away the fear and see what is going on. Not all missions were that bad. But on almost every mission, we got waves of flak. Flak is anti-aircraft fire. You know how important your mission is by how heavy the Germans would protect the target with a barrage of exploding shells. We wore protective gear with metal suits and metal helmets during the bomb runs. Sometimes pieces of flak would cut through the glass and penetrate our armor. But my job is to concentrate on my crossers and targets. That’s the job.

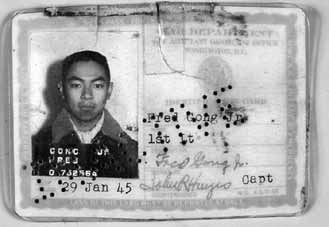

First Lieutenant’s 1945 identification card.

Photo courtesy of Duty and Honor.

A bombardier uses statistics, and you have a book almost as thick as a telephone book. I was setting up for a bombardment. But air was leaking through my plane. So I put my foot on my book to prevent it from flapping around. I felt a jump. I looked, and my foot was still there. So I go back to concentrating on my bombs. Then I picked up the telephone book, and a piece of flax had gotten halfway through. That was the closest I got to being wounded. The next day, there is another job.

You had to be young to survive in that environment. In the Battle of Britain, Churchill said the young fliers that saved England were teenagers who thought it was a game. That was part of our feeling too. There were ten of us in my plane—four officers and six enlisted men. It was our first time away from home. We officers were all about twenty or twenty-one years old. The head pilot or crew captain was about twenty-four. He’d been a sergeant in infantry. We called him “Old Man”. The youngest gunner was seventeen years old who had lied about his age to get in. After about five or six missions, he said, “I can’t fly anymore; I can’t sleep.” No one said anything because we all understood. It could be so scary.

One time, we almost collided with a German fighter plane. I was looking in front of me and a voice called out, “One at 9 o’clock.” I turned and swung my guns around. He dived under my nose. I could see him. What a gutsy guy trying to ram us. But then I saw one of our fighter planes was right on his tail.

My proudest moment was getting the Flying Cross. The 15th Air Force got a direct order from London that our allies in Yugoslavia were planning a drive offensive to push the Germans out. They had trapped the German infantry battalion in a town next to a river. There were two bridges across that river: a railroad bridge and a road bridge. Our spies knew that German reinforcements were coming so it was urgent. London Supreme Headquarters told the 15th to blow up these two bridges before reinforcements could get there, and it would be a three-squadron attack. I knew it would take three squadrons to blow up those two bridges. It was important to overload, to send more than necessary so those bridges would be blown. The middle bombardier was fairly new to this group. I flew the last squadron; my job was to make sure the bridges would be hit.

We crossed the Adriatic Sea, each of us flying independently. We were in bad weather or “soup” for half an hour. When we came out of it, our other two squadrons were not there. We did not know if they had gotten lost. Bombardment pilots are trained to fly in squadron formation even through the worst kind of weather. Fighter pilots are trained to do acrobatics and not fly in formation. In thick fog, they may be afraid to run into each other’s wings. I checked my maps and my time, and we were exactly where we were supposed to be. A bombardier memorizes the terrain so when you get there, you know you’re there. Even without my binoculars, I could see those two bridges waiting for me. The pilot called me. We only had three planes behind us instead of sixteen planes. But we both said at the same time, “Let’s go.” It was my twenty-eighth mission. With all that experience, I knew I could hit it. I put my crossbars between those bridges; they were about two hundred feet apart. There were about three splashes in front of the first bridge. Missed. Then I saw about four flashes. Hit the first bridge. I lost two or three bombs between the bridges and all the rest hit the second bridge. That was the most thrilling moment of my military career. It was an important mission helping our Yugoslav guerrillas. The Flying Cross is the highest Army Air Corps honor.

I made close to fifty missions or thirty-five sorties. I flew mostly the Boeing B-17 and finished on the Lockheed P-38 Lightning. I made my quota. I have three oak leaf clusters under my Air Medal. I’m lucky to have survived. I left the service in December of 1945.

My military service gave me clear direction, a certain confidence, and an appreciation of America. As a cadet, those white glove inspections were rough so you learn to be orderly. As cadets, you have two buttons. One time, my one button was not buttoned (laughs). It wasn’t serious enough to keep me on the weekend (laughs). We learned to work as a team; the ten people in a bomber have to depend on each other. Another benefit was the G.I. Bill. Coming from a poor family, I could never have attended Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. I’m a retired commercial artist. A lot of the other officers stayed in the military or went into engineering.

I was very good in art since I was a little kid. I was a featured in the Sunday newspaper at home when I was near the second grade for my drawings on the sidewalk. This retired art teacher read the story and came to help me continue to draw. For about six years, I went to her. She always had a still life, quite often watercolor flowers. In high school, my art teacher also took a special interest in me. When I was in the military, I thought that if I survive this, I will go to art school. And I did.

Today’s young people have advantages we never had. Women have advantages that they didn’t have in my generation. But I think I’m a lucky guy. It was a great time to become a flier. Prior to that, I was a second- or third-class citizen. With the uniform, I was a mainstream American. That’s part of my story.

_______________________

1 Excerpted from the Friends of the Chinatown Library website: Fred Gong was born in San Francisco to Fred Gong, Sr. and Mae Law. Fred was the second of five children. Fred’s parents entered the United States from Mexico in 1922. In 1936, his parents were named in deportation proceedings because they entered this country illegally. According to a newspaper article, ‘Portland clergy, newspapers, congressmen, and friends came to their rescue. The proceedings, which would have separated the parents from the children, were dropped in 1939.’ Fred was a talent young artist. In 1941, his painting entitled ‘What My Community Has Contributed to the Nation’ won the American Magazine Youth Award for the best design for a mural based on American tradition.

____________________

2 Summarized from Him Mark Lai’s “Roles Played by Chinese in America” (Chinese America: History and Perspectives, 1997, pp. 80-81): As the Sino-Japanese War intensified in the early 1930s, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) in New York had a grandiose goal to train Chinese American aviators that would help defend China. The Chinese Aviation School for National Salvation aimed for $20 contributions from 10,000 individuals to train 3000 aviators in six months. This unsuccessful plan triggered a smaller effort by the Portland CCBA and Kuomintang Party. By 1930, the Portland community had graduated eight aviators from the nearby Adcox School of Aviation and purchased a training plane. In the two classes of 1932 and 1933, Portland’s Chinese Aeronautical School graduated another 60 or 70 Chinese Americans. Of these, 32 joined the Chinese Air Force. The two female pilots that graduated from Portland were Hazel Ying Lee and Wang Guiyan. Both went to China but women were not allowed to join the Chinese Air Force as pilots. The Chinese Aeronautical School closed in 1933 due to the lack of funds.

3 Most likely, the Santa Ana Army Air Base (SAAAB) of the Western Flying Training Command.

4 Fighter aircraft are designed primarily for air-to-air combat with other fighter planes. Bombers and attack aircraft are designed to attack ground targets.