Editor’s note: In this collection, we asked some allies to voice their concerns. Gum Saan Journal is grateful for these contributions.

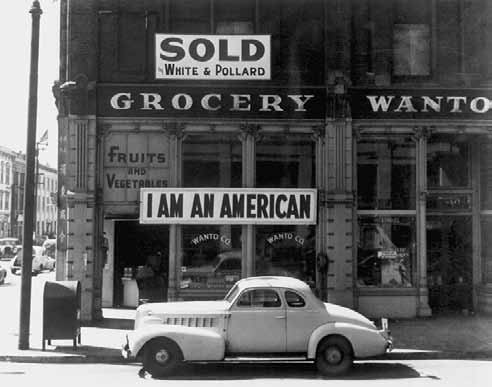

The photograph is by Dorothea Lange, taken in March of 1942, during the time she worked for the War Relocation Authority (Library of Congress Reproduction No. LC-USZ62-23602).

Roy Nakano

Nakano is a Sansei and in 1980, a co-founder of the National Coalition of Redress and Reparations, now Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress (NCRR).

In 1942, my U.S.-born parents were forced to bring their small children to live in converted horse stables at the Santa Anita Racetracks before being incarcerated in a concentration camp in Jerome, Arkansas. They were later moved to the maximum security Tule Lake Segregation Center—in Northern California—after protesting the incarceration. In Tule Lake, my parents became renunciates, losing their U.S. citizenship in the process. It was not until 1946—a year after the war ended—when they were released from the camp

Today, there’s a State Department of Parks and Recreation plaque at Tule Lake that reads: “These camps are a reminder of how racism, economic and political exploitation, and expediency can undermine the constitutional guarantees of United States citizens and aliens alike.” The inability of individuals and institutions to see Americans of Asian ancestry as anything but foreigners also played into this. Today, it’s a war against a pandemic—and we have once again become the scapegoat for those who still can’t see Americans of Asian ancestry as anything other than foreigners. We are all in this together. Like Tatsuro Matsuda in the 1942 Dorothea Lange photograph, we are still trying to fly the “I Am An American” banner—80 years later.

Ralph Walker

For almost thirty years, “Conversations with Ralph Walker” is a staple of interviews on local access television station, KGEM, of Monrovia. Called “The Voice of Monrovia,” Walker has been a community conduit especially on African American issues in the San Gabriel Valley. He is a member of ChangeMakers. A week after the killing of George Floyd in 2020, Monrovia was one of many Southern California cities that had daily multiracial Black Lives Matter rallies. City Council responded to concerns by establishing an ad-hoc Committee on Equity and Inclusion.

I was raised in Southside Chicago in the days of Emmett Till, Fred Hampton, and the ‘68 Democratic Convention. After the 1979 Chicago blizzard, I escaped to Los Angeles only to be confronted with job discrimination, the 1992 Race Riots, and almost daily reminders that I’m an African American man. I could hardly watch the George Floyd incident on television. That officer that had his knee on Floyd’s neck had the look of death. I knew. There are so many already on “The List” of victims, that if you name one, you do injustice to all the others. There have been so many men, so many women, and even so many children whose names are on The List.

“Asian hate” has always been the elephant in the room. Some Asian Americans have tried to assimilate into the White norm. They may emulate the White culture by changing their eyes, their lips, their voice, and their names. One of my Chinese immigrant neighbors was proud to wear his MAGA hat.18 Hollywood has played a major role enforcing stereotypes of Asians as the model minority.

The killing of George Floyd at the same time as the rise in anti-Asian hate crimes was a reminder that Asians are not White and have always been viewed as the foreigner or the enemy by insecure White folk. 2020–2021 was a reminder that systemic racism runs deep against both Asian Americans and African Americans.

It was really special to hear young Asians speaking out about the harassment and the racial battles they have endured over the years. The struggle continues for them also. This year, we got to hear their voices as they marched with us.

One of my favorite quotes is from Yuri Kochiyama, who cradled Malcolm X after he was shot, “Keep expanding your horizon, decolonize your mind, and cross borders.”

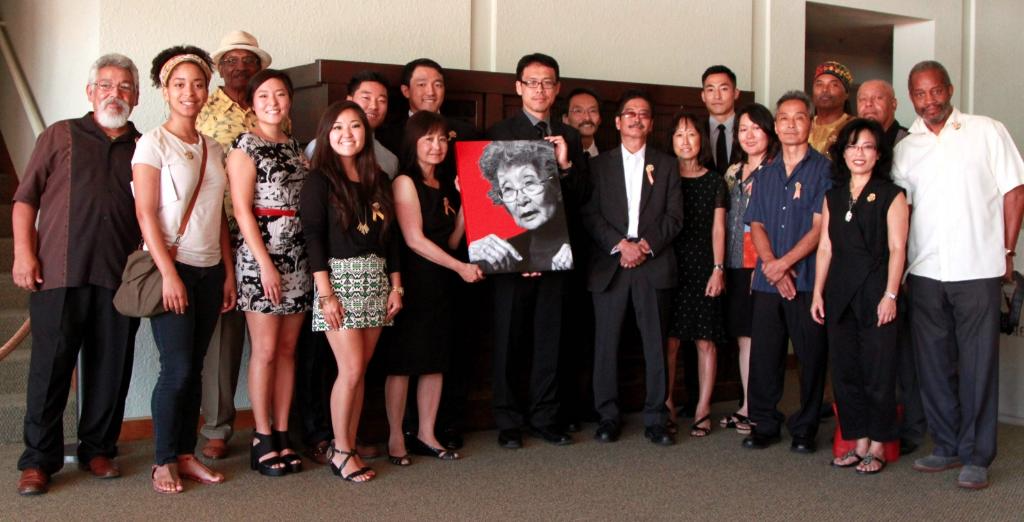

Photo courtesy of Ralph Walker.

Prince Bhojwani

Bhojwani graduated from UC Santa Barbara in 2013 and is CEO of ASANA Voices, the Alliance of South Asians in North America.

I am the son of Pakistani Hindu refugees—a square peg in a round hole. My identity has been molded by the anti-Hindu violence that forced my parents out of their home country, the Rodney King riots in L.A. that shaped my views of race relations, the surge in anti-South Asian hate crimes after 9/11 that made me question if I was truly an American, and George Floyd’s brutal murder that led to a realization that my community’s voice is too fragmented to be heard by decision makers in times of need. Weeks after Floyd’s death, my friends and I founded ASANA Voices, the Alliance of South Asians in North America, in an effort to build the infrastructure to drive economic, political, and social change for South Asians in North America.

Another gap, in my opinion, that must be filled is the fragmentation of Asian identities and the need for pan-Asian solidarity in both good and bad times. South Asians, although technically Asians, are rarely considered Asians and are often left out of discussions centered around AAPI identities. On the other hand, South Asians rarely involve themselves in AAPI discussions, because they may not consider themselves Asians! We must all stand up, reach out, and collectively weave the social fabric that will narrate the Asian Pacific Islander Desi American (APIDA) experience going forward.

Jireh Deng (she/they) 鄧以樂

Poet. Writer. Opinionator. A student at Cal State Long Beach, Jireh was intern with the Los Angeles Times in 2021. She grew up in the 626 San Gabriel Valley region.

I grew up in the San Gabriel Valley all my life and really didn’t understand how different this entire area was because I just accepted that we had signs in Chinese and that the entire community looked like me. I always felt different because I was queer, and when I finally came out, I also expanded my community to the writers and poets who taught me to express myself. I’d like to think that I developed a strong Asian identity from being raised in this community, but I also feel like I grew up in a bubble. Moving to college was really hard for the first few months because there was such a culture shock. Even though I was born in this country and I speak English, I felt like I had lived in an alternate reality of Asian America for 18 years of my life. Since taking an ethnic studies class in college and just learning more about what it means for me to be queer, I’ve come into a stronger and purposeful mission to do work that amplifies my community and hopefully continues to expand representation. There aren’t enough Asian American queer femmes in journalism or poetry. There will never be enough until all of us have a seat at the table.

When I saw the anti-Asian violence in the news and the harassment that people were reporting at school, I was so saddened because it took the shooting in Atlanta, Georgia to notice that the Asian American community was hurting. We need to dismantle this idea that we are the model minority. Yes, Asian Americans are some of the richest people of color in this country, and yet, we are also some of the poorest. There are nuances to this idea that all of us fall into this neat category when you look at the world, and Asian people make up a majority of the world’s population. After the shooting in Atlanta, I acutely felt how Asian women are constantly relegated to the margins, ignored, or seen as submissive or quiet. Most of the Asian women I know are loud and boisterous, but in speaking English, a second language, that’s why their voices are more uncertain. I wanted to take back my autonomy so I shaved my head. I didn’t want to be colonized by other people’s perception of what gender or respectability looked like on my body. I wanted to take ownership and say I was and I am enough.

Everyone comes to the San Gabriel Valley for the Chinese food but it’s so much more than that. There’s an entire community of Asian Americans that have formed out of need and protection. We endure here because we have relied upon each other.

Dr. Ernesto Bustillos

The Bustillos family has been in the San Gabriel Valley since the days before the 1848 Mexican-American War. His mother went to school with Japanese Americans at the then-segregated Lincoln School in San Gabriel. Dr. Bustillos teaches Chicano Sociology at Pasadena City College.

My childhood memories of San Gabriel and Rosemead didn’t include much anti-Asian sentiment. I remember that my grandfather had a good relationship with his neighbor, Joe Takiyama, that went back to before World War II. My mother went to school with the children of the Yoshimura family who founded the San Gabriel Nursery. In addition, my Aunt Laura would often bring her Japanese American friend, Evelyn, to my grandparents’ home. In school, our playmates included kids named Nakamura and Samashima. The fact that we grew up with them meant that we really didn’t think much about their Japanese descent. Later, during high school, my brother had a close friend named Mark Shibukawa who often came to our house. I remember going with my brother to the Shibukawa home and being welcomed. I believe that Mark ended up marrying a Mexican American.

However, I do recall an increase in anti-Asian sentiment once large numbers of Chinese began to move into Monterey Park sometime in the 1980s. The sentiment mostly came from the Anglos, but you might occasionally hear something from a Latino. The rise in the population caused alarm and led to several attempts to preserve the status quo. There were fights about multilingual business signs and speaking English. But when the Anglos saw that the Chinese were here to stay, they began to move out, and I remember seeing graffiti that read, “Will the last American out of Monterey Park please take the flag.” The implication was that Whites who were leaving were the real Americans. I also remember one of the White men my mom worked with complaining about “Chinese dentists” buying up real estate. Mostly, it was such a rapid change that it caught many longtime residents off guard.

When I moved back to San Gabriel after graduate school, there had been a lot of changes, and the barrio was disappearing. Many of the stores and houses were torn down, and people were saddened by the loss of their community. One aspect to the change that led some to not like the Chinese was that they only tended to interact with other Chinese. Unlike the Japanese who had gotten along well with our people, the new residents tended to stay away from us, and many Latinos got the feeling that they looked down on us. My son’s experience with the Chinese Americans seemed to be quite different than mine with the Japanese Americans.

Ernesto Jr. said that it was difficult to make friends with Chinese kids at Gabrielino High School. He tried, but it never really happened. I didn’t know what to make of it. My son tends to get along with all kinds of people. Maybe they weren’t into rock music like him. Perhaps, unlike the Japanese Americans I remember from my youth, Chinese immigrants haven’t lived around Mexican Americans that long and probably don’t know much about us, except for the negative stereotypes that they see on TV and films.

Florante Peter Ibanez

Since the 1970s, Ibanez has been in leadership with the Union of Democratic Filipinos (KDP), Search to Involve Pilipino Americans (SIPA), and Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS). Ibanez is author of Filipinos in Carson and the South Bay and retired from teaching Asian American studies at Loyola Marymount University and Pasadena City College.

Growing up as a Filipino American in Wilmington and Carson, I attended Banning High where we all seemed to get along in a Chicano, Black, and Asian Pacific Islander student body. It was kinda sorta like the Breakfast Club cliques of jocks, nerds and social/leadership kids all made up of different ethnic groups. I joined the Human Relations Club to get to know others better; we were sent to attend some race awareness conferences at other high schools. I knew at that stage in my life that there was discrimination especially against African Americans and Latinos, but I felt it was more in the form of “microaggressions”—to use today’s terminology.

Living with my father part-time in Watts, I witnessed first-hand the Watts Riots in 1965. In college, I got involved with forming the Asian American Students Association at CSUDH, and helped form Filipino American clubs at UCLA and UCI. As an EOP special admit19 at UC Irvine, I took classes in their Comparative Cultures Program and learned about the Third World and imperialism. I felt I had a good understanding of racism.

I’m saddened by the rise in hate crime against Asians, especially against our elderly—now including myself. I had my own taste of this, unfortunately perpetrated by a Black youth. While he exited the Blue Metro Rail in Compton, he purposely slapped my head as he passed me. I had never even made eye contact with him before the attack. I heard other people on the train mumble, “Did you see that guy hit that old Asian dude?” I sat silent in my seat. I felt stunned.

_______________________

19 Equal Opportunity Program (EOP) was created on some campuses as early as 1966 in response to pressures from students of color. In 1969, SB 1072 and SB 164 incorporated the program into the California Education Code. At the CSUs, UCs, and community colleges, EOP programs mentor historically disadvantaged and first generation college students. Counseling, tutoring, and financial aid continue today.