By Dr. Gay Q. Yuen 阮桂銘

Editor’s note: Dr. Gay Yuen is Board Chair of the Friends of the Chinese American Museum. She was a professor of education at Cal State University Los Angeles and Board President of San Gabriel’s Asian Youth Center. In 2021, she was appointed to the LA County Human Relations Commission. She lives in Monterey Park. This is from an interview in July of 2021.

Unfortunately, the 1871 Chinese Massacre in Los Angeles was not unusual. Such things happened in those times. And the forgetting of this history is also nothing unusual. This Massacre is on a continuum of hatred against the Chinese Americans, Asian Americans, and other Americans of color. Even today, the hate continues within an environment of nonchalance and denial.

Anti-Asian Hate Between 1871 and 2021

The Los Angeles’ Chinese American Museum (CAM) is in the Garnier Building at 425 N. Los Angeles Street—literally right where the Chinese Massacre happened in 1871. The Garnier Building is one of the most important Chinese American structures in the history of Los Angeles as it housed major Chinese American centers such as the Sun Wing Wo dry goods store and Chinese family associations. The building was built by a French settler, Philippe Garnier, in 1890. Every year, CAM commemorates the 1871 Chinese Massacre.

2021 was the 150th anniversary of that shameful incident in history. Every year the commemoration program includes the reading of the names of the victims. I want everyone to hear the names. We know the 18 names that were lynched or killed by that Los Angeles mob, but only the English names. As we are reading these names, I wonder if we are pronouncing the names correctly. What were the Chinese characters for these names? We know that “Ah” 阿 in Ah Choy or Ah Wing is not a name, but a Cantonese affectionate term perhaps meaning “friend.” What were their given names? What are the right pronunciations for these names? Are these Taishan or Zhongshan names? Where were they from, what were their stories, who did they leave behind?

The issues of racial superiority and power are still prevalent. When White people’s power is touched, there is a kickback. In 1871, the power structure perceived no problem that Chinese Americans fought each other and that Chinese women were abducted and enslaved. But when a White saloon person—Robert Thompson—stepped into the line of fire and was inadvertently killed by the Chinese, then it was a different story. Then the mob ensued. In the same way, society allows African Americans to kill each other even today, especially if it is relegated to “their” segregated communities. But if a White person is harmed or a White woman is disrespected, then it is a totally different story. If Robert Thompson did not get in the middle of the argument between the Chinese men in Chinatown that night, the L.A. Massacre would never have happened.

In the same way, George Floyd challenged the White power structure in 2020. How dare he defy an empowered White police officer of authority. How dare he not get into patrol car when he was ordered to. How dare he attract a crowd of sympathizers. The White officer’s authority was challenged. The White officer had to show that he was the authority and held the power over those on site at the time.

The Hmong police officer with Derek Chauvin, Tou Thao, was like an Asian extra in the old Hollywood movies. Thao did not go against his superior to help Floyd. He didn’t say anything. He just stood there and kept back the small crowd using cell cameras to record and help Floyd. Thao did what he was paid to do. Tou Thao had worked hard to become an officer, and he probably thought he found his American dream in being an officer.

Coalition for a Better L.A.

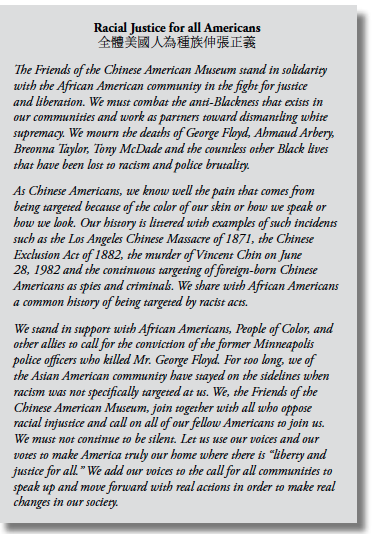

After the 2020 George Floyd incident, the Friends of the Chinese American Museum had to make a very difficult decision. CAM is chartered as a cultural and educational nonprofit institution and very dependent on charitable giving. Our donors’ political views range from conservativism to liberalism. Should we make a support statement for George Floyd and Black Lives Matter? Isn’t our Chinese American history on that same continuum as George Floyd? I went through a lot of soul searching. What if I alienate some of our donors? What are my responsibilities and priorities? I gathered our Board together, and we became one of the first Chinese American organizations to come out with a statement entitled “Racial Justice for All Americans” on 2 June 2020.

At that same time, the statistics of hate crimes against Asians was climbing. It spurred mainstream media attention. We were aware of daily reports. Like others, I was getting more and more uncomfortable. I called a meeting with some like-minded leaders and friends from the Chinese American Citizens Alliance (Munson Kwok), Chinese Historical Society of Southern California (Eugene Moy), the Chinese American Museum (Paula Madison), and others to talk over our concerns about AAPI hate. We recognized the fact that we have to build coalitions to address our front boiler concerns. We have friends who are leaders in other ethnic communities. We know we can’t do everything, but we needed to prioritize.

We built Coalition for a Better LA. There are about twelve of us in the Coalition. We meet every Wednesday morning diligently. We decided that in order to be a true coalition, we need to tap on the leadership and activism of other communities of color. Those who join us include Michael Lawson, President of the Urban League; Jose Calderon, professor of sociology at Pitzer College; Robert Sausedo, President of Community Build; and Connie Chung Joe, CEO of Asian Americans Advancing Justice. These are people who have the pulse of their communities. First, we want non-Asian friends to understand this pressure on us today as Chinese/Asian Americans. The same issues impact all our communities, and we need to support and listen to each other.

Our first focus in 2020 was to improve census results. Then we tried to do community action for California Proposition 16, the affirmative action bill that was defeated in the November 2020 elections. We next focused on police reform and have met with Los Angeles Police Department Chief Michael Moore several times already to discuss the reimagining and reform of current practices, including application, selection, training, promotion policies, etc. In front of us is the redistricting challenge. Because of the loss in the census count, we are concerned about forthcoming changes in the San Gabriel Valley. We need to be ready to mobilize our communities.

A lot of this onslaught of racism was triggered by the Trump administration. Racism in the U.S. has always existed and can be viewed as a continuum. When the economy is strong, Chinese and Asian Americans are welcomed as workers. But when times are tougher, “immigrants” and “foreigners” are accused of stealing jobs. The former president dug up the already existing racism and prejudice in order to support his conservative power base. Unfortunately, pointing blame at Chinese Americans for the pandemic and accusing Chinese American scientists of being spies actually exacerbated the hate and racism against all AAPIs. The truth is that many Americans still cannot perceive the difference between Chinese, Chinese Americans, Asians, and Asian Americans, thereby bringing hateful language and cowardly violence against anyone with API features. We saw the same thing with the concentration camps of World War II when Japanese Americans were unjustly interned. Trump played that same card with his stigmatizing labels of the coronavirus as “China virus,” “Chinese virus,” and even “Kung Flu”. Trump blamed the pandemic on a “Wuhan lab leak.” Trump muddled foreign policy with xenophobia against American citizens. In fact, how many Chinese Americans work in the healthcare frontlines and in formulating the vaccines? These people should be acknowledged as heroes, not vilified.

A UC San Francisco study by Dr. Gilbert Gee published in the American Journal of Public Health (March 2021) shows a statistical correlation of anti-Asian hashtags the week after Trump first tweeted “the Chinese virus” slur on 16 March 2020. The study shows that the former president’s use of language had a direct impact on anti-Asian sentiments.

40th Anniversary of Vincent Chin’s Murder

The Chinese American Museum also had a Zoom retrospective program on the Vincent Chin case. In that Detroit case, the two perpetrators, Ronald Ebens and Michael Nitz, never spent time in jail. They were given the same punishment as the perpetrators of the 1871 Massacre—no punishment for their actions. This was the decision of a judge who decided that Ebens and Nitz were “good people.” Ebens and Nitz chased after Chin for 20 minutes and beat the man to death with a baseball bat. Yet, these White men were protected by the law. In the 1854 People v. Hall case, the California Supreme Court determined that Chinese—like Indigenous and African Americans—cannot testify against Whites. That law may be overturned but the sentiment is still there. In the 2021 Atlanta case, Captain Jay Baker of the Cherokee Sheriff’s Office said that the perpetrator—Robert Aaron Long, a White man who gunned down eight people—was just having “a really bad day.” This is systemic racism, and it is so deep and entrenched. It is all connected. It can happen again; it is happening again.

Speak Out and Be Heard

We Chinese Americans need to voice our concerns. We need to go against our thousand-year culture. One of the Confucian classic teachings, Doctrine of the Mean 中庸, suggest we have to gingerly walk the middle road. Our culture says to not voice your opinion, don’t laugh too loud, don’t stand out. Perhaps that teaching also causes Asians to endure silently. But we need to make our own choices. I want us to be heard. I want us to speak out for those who can’t speak. I want to speak for those who are afraid. It’s hurtful to hear people say, “I’m not only afraid of COVID, I’m afraid of being beaten up when I go walk my dog.”

Not being heard does hurt us. Look at all those who’ve been unjustly assaulted for doing nothing. LAPD at one point said they only had one reported case of hate crime; it is partly on us to report all the incidents. Chinese say “算了,算了(suan le, suan le or never mind), I don’t want to cause more trouble”. We need to work within the American system and speak out.

The group that were young activists in the 1960–70s Asian American Movement is now in our 70’s. And we are still fighting the same fights. Yes, we’ve made gains. We have identified our own heroes, our own issues, and our own Chinese American history. But we are aging, and my body is more tired. Because of the pandemic, we were not out there at the rallies. I’m not quitting but we need a whole new generation of vocal fighters. Happily, I know that they are out there. Definitely there is hope in the mobilizing ofyoung people, especially through social media. There are new community activists and scholars. And there is much more diversity speaking out among the AAPI groups, with Tongan Americans, Cambodian Americans, Vietnamese Americans, etc. visibly and vocally joining the fight. That gives me hope.

From the 1960–70s, we knew that our strength would be through coalition building. We can only take care of our own community if we help others empower their communities. No lives matter until Black lives REALLY matter in this country.

published 2 June 2020.