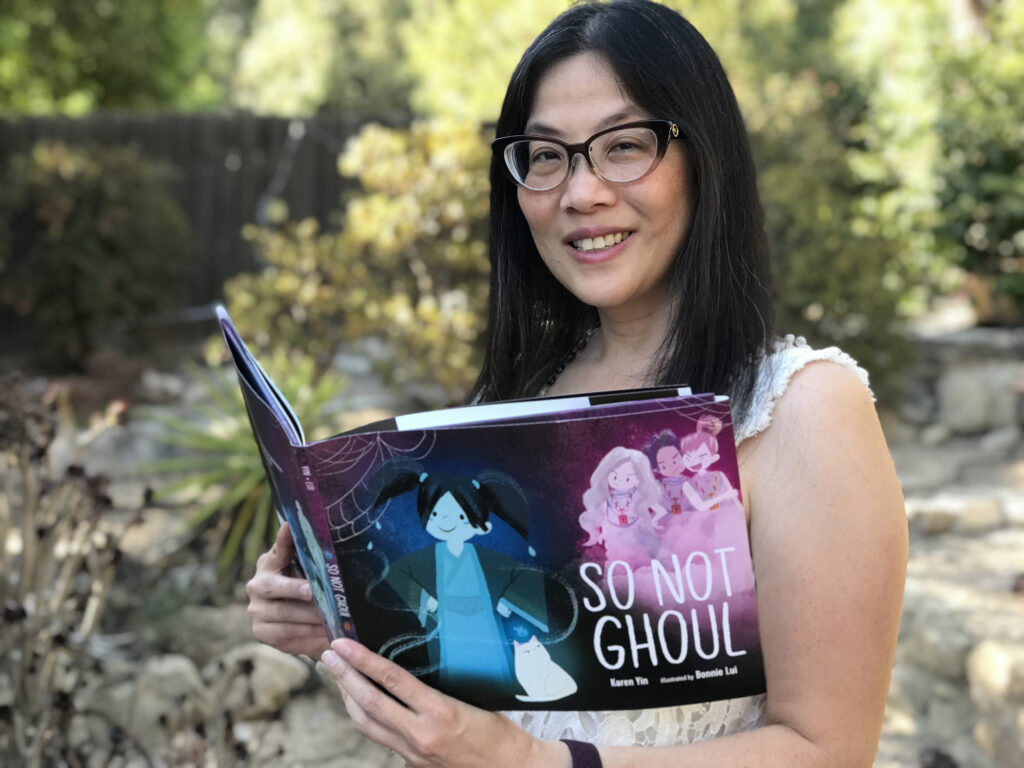

Editor’s note: An award-winning American writer of Chinese descent, Karen Yin is the author of children’s books including Whole Whale and So Not Ghoul and a forthcoming book on conscious language. Karen is the founder of Conscious Style Guide, The Conscious Language Newsletter, the Editors of Color Database, and AP vs. Chicago. This is transcribed from an interview on 9 August 2022 in Monrovia.

American ghost in bicultural limbo. Illustrated by Bonnie Lui.

Photo courtesy of Karen Yin.

Fierce Lineage of Women

My waipo 外婆 had bound feet. In Shandong 山東, when my mother was nine months old, my waipo plotted to escape the Communist regime while the militia surrounded their home. When the heavy rains made a hole in the wall, my waipo waited till it was pitch black before leading her family quietly through the crumbling wall to the outside. Half a kilometer away, she remembered my baby mother still sleeping at home and went all the way back to get her. She died in 2004 at the age of 97, surrounded by family in Northern California. I grew up hearing this fierce story, and I am proud to be part of this fierce lineage of women.

I’m the second child out of five, but I tell people I have been the youngest, the middle, and the oldest. When I was born, I was the youngest. When my younger sister was born, I was middle. When my older sister moved out, I was the oldest. So I’m used to having many roles, many perspectives.

My mom did not have a strong support system. My parents came to Canada and the U.S. alone in the 1960s, and it wasn’t until I was a teenager that her family started to ask, “Please vouch for us [to immigrate to the United States]”. After they came over from Taiwan, within a year or so, they moved to the Bay. So we were alone again in Southern California. And my father would travel for long periods of time. My mom had to fend for herself while raising four children. I am deeply grateful to my mom for her sacrifices.

She is progressive in so many ways. Unlike some of her peers, my mom did not pressure us to have children. She did not believe in assimilation. She wanted us to speak only Mandarin at home. I wish that meant my Mandarin is good, but it isn’t. Once I started going to school, I began to lose my mother tongue. Now we text each other. It’s weird to be using English with my mom, because I associate that with disrespect, but what can you do, I can’t read Chinese.

Photo courtesy of Karen Yin.

My father was born in Jiangxi 江西. He had an engineering degree from Taiwan. My father was gone early on in my life, so I don’t have his stories. But I remember that he was really unhappy. He had a lot of odd jobs. They divorced when I was 10; then they remarried; and they divorced again when I was 12. Children usually don’t want their parents to divorce, but we were thrilled. We were thrilled because it was not going well. When they got married again, I was so upset.

We moved around a lot, so I was always a new kid. That was a hardship all its own. I remember this girl who called me a bitch. I was six and so shy. I didn’t even know what that word meant. We moved seven times before I was a teenager—Hollywood, Monterey Park, Rosemead, back and forth. Even though we moved to Southern California when I was four, I still identify as a New Yorker, because the very first memory I have of being different was of kids in California saying “ant” instead of “awnt” [for aunt] and “vayce” instead of “vahz” [for vase]. That burned into my identity. I’m a New Yorker, and that’s why I didn’t belong.

Tiger Child

My mom never bothered me about grades. She assumed I would do well. I remember once I got a C on my progress report, and I was so excited! I said, “Mama, look, I got a C!” Because I had gotten high grades this whole time. And she was like, “Oh, I’m sure it’ll be fine.” Really? That’s it? So it was I who was really ambitious, really competitive. I had to beg for piano lessons. I did not have a tiger mom. I was a tiger child.

From a young age, I had a heightened sense of injustice. I was an activist without knowing the word for it. I had zero support. My motivation was completely internal. I was sensitive to the wholesale hatred of people. If you’re going to hate me, make sure it’s personal and not categorical. My concerns about sexism were stronger than my concerns about racism, because I didn’t get anti-Chinese racism at home, but I did get sexism at home. That’s why sexism has always been more acute. Anti-queerness, to me, is a type of sexism.

Being Chinese American was an advantage. It gave me a more complex perspective, forced me to ask questions. I could observe how gender ideals differed between two cultures. It was a game, and I didn’t want to play. So I detached from gender. Every time somebody referred to me as a girl or a lady or a woman, I’d be shocked. Like, they’re talking about me? Shocked every single time, even today. Imagine if people referred to you by your race for no reason. Like saying, “Karen bought Chinese-self a book.” How racist is that? To be clear, I’m not trans or nonbinary. I just don’t believe in making gender relevant when it isn’t. I’m OK with she/her pronouns, because they’re easier for everyone, myself included. My despair with the world has more to do with attitudes than words.

In high school, I was known for fighting injustice. When we voted on the “royal court,” only the boys were allowed to vote on girls. I remember saying to the vice principal, “This is sexist.” When I became the editor-in-chief of the school newspaper, I would tell the admin that we’re doing an editorial on the recent bomb threat and why nobody was excused from the campus. The principal censored my writing several times. Freedom of speech in high school was not protected back then.

I graduated as co-valedictorian. It’s a fun fact, but it’s not really an achievement. AP classes began midway through high school, and it messed up our point system. Anyone with at least a 4.0 was co-valedictorian. At least, that’s what I remember. And I was voted Most Studious, which was racist, because I never studied until college (laughs).

Later, I used my growing platform for change. When the Associated Press Stylebook added entries for lesbian, gay, transgender, and LGBT around 2014, they left out bisexual, even though LGBT has a B. It took me years of sporadic communications to convince them to add bisexual and asexual. I succeeded by the 2019 edition. Then they consulted me on other terms throughout the stylebook, so I raised the problem with coming out, a personal pet peeve. I said, it’s being used regardless of whether the person is coming out. Why does talking about your queerness automatically mean you have shame about it? If I say I’m Chinese, did I come out? It others queerness. So a usage note on coming out is in the AP Stylebook now, too.

Queer Origin Story

I’ve always had crushes on both boys and girls growing up. Male and female teachers. I’ve assumed that this is common. I never thought, this is the beginning of my bisexuality.

I went to the University of Redlands, specifically the Johnston Center [of Integrative Studies]. I was studying feminism and became deeply uncomfortable with how my anti-sexism stopped when it came to attraction. I asked myself, why do I think I’m not attracted to women when I’m not attracted to anyone? It was philosophy- and equity-driven. I realized that whatever I am, it’s equal. I’m either asexual or I’m bisexual. Because otherwise, it was like telling myself, don’t be sexist except for this one thing (laughs). Recognizing my capacity for gender-free attraction helped me be grounded in my anti-sexism.

The next day in class – it was a course on the psychology of interpersonal relationships – I immediately announced that I’m bi. So I consider myself never having been closeted. And keeping in mind how old I am, I’ve also been out at every workplace. I grew up angry, and that helped me be fearless. I was weird and I was angry, and I saw no reason to hide who I am. Most queer people come from a place of shame, but I came from a desire for egalitarianism. That’s a big difference. Who’s going to argue with me?

Therefore, I didn’t have the typical struggles. My struggles were more like – I was invisible. I was talking to a woman at a lesbian bar, and she asked, “Are you straight?” I said no. Then she goes, “Are you gay?” I said no. Bisexuality was not an option in her mind, so she was really confused. So that’s what I had to deal with, where it’s like, OK, I guess I don’t exist (laughs). Now the majority of LGB people identify as bisexual. You can be bi and remain bisexual. It doesn’t exist as a stepping stone to being gay, and it doesn’t have to change when you are partnered.

You don’t need sexual experience to identify as bi. A lot of kids identify as straight, but have they kissed or had sex? So as soon as I had that awareness, I can identify as bi, because it’s only fair. I was not thinking sexually until later. It wasn’t like I was hot for only guys and then I had to reconcile that. I wasn’t hot for anybody. My sexuality evolved organically with my philosophy of sexual freedom.

To be honest, I don’t love the word bisexual, because you have to keep explaining that bi doesn’t mean men and women. It’s my gender and another gender. So I prefer queer. I’ve tried pansexual, but queer is more comfortable. When I entered the queer community in the mid ’90s, queer was already widely accepted. I remember this one girl saying, “I love the q. It looks like a cat tail.” And I was sold. It sounded adorable. It’s an umbrella term that covers so much. I can be fluid within queerness. And I don’t have to keep updating people if my identity shifts.

When I was in my mid-20s, I told my mom that I do not believe in discriminating against men or women sexually or romantically. To speak her language, I said that we all have yin, we all have yang. So I don’t need to be with yang to be complete. At first, she was upset. She called up my older sister and said, “You have to talk to her, you have to tell her it’s wrong.” My sister said, “But it’s not wrong.” To my mom’s credit, she forced herself to come around. I think my mom was more upset about me becoming vegetarian when I was 19, because it took her years to accept it. Whereas in one month, she accepted my queerness.

goofing around, 2012.

Photo courtesy of Karen Yin.

Chosen Family

My partner and I were friends for years before we became a couple. She’s Korean American. We met at a meeting for LAAPIS, the Los Angeles Asian Pacific Islander Sisters – basically, a community of queer API women in L.A. I used to be active in queer spaces, even joining a queer community chorus, but became disillusioned by in-group prejudice and other problems. Before LAAPIS dissolved sometime around the year 2000, I had a role on the board, did stuff for the newsletter, handled PR, hosted parties. Many of my current friends are from the LAAPIS days. It was the first time I had close female friends since college, and being around other Asian American women changed my life.

Her bunnies moved in 6 months before she did. Because we are Registered Domestic Partners in California, we decided not to get married when it became legal. Which is a relief, because we’re both opposed to the idea and institution of marriage. I mean, as early as age 12, I told my mom I would never marry. I haven’t found a reason to break that vow to myself.

The Art of Justice

Even though I’ve been an editor for decades, it isn’t my dream job. In school, I was praised for my way with words, so it was always in the back of my mind that I wanted to write. The first short story that I wrote after I quit my editing job in 2012 went on to win a $2,500 grant. One thing led to another, and I started writing picture books in 2019.

Illustrated by Nelleke Verhoeff.

I wanted a social justice bent to my stories. I wrote my first book, Whole Whale, when the U.S. government was tearing families apart at the Mexico border. I asked myself, how can we fit immigrants in? How can we be creative about this? So that’s how Whole Whale came to be. It was about a hundred animals trying to cram themselves into the book, but is there space for the whole whale? The animals must work together to find a solution.

My second book, So Not Ghoul, is about a Chinese American ghost who wants to dress in sheets and chains like the other ghosts. But her ghost ancestors want her to dress like a Chinese ghost – in her case, a diao si gui 吊死鬼. This is my bicultural story but in a ghost world. My parents wanted me to be a certain way, but other people wanted me to be another way. And the tug of war is so damaging. Two other books are coming, from Scholastic, and they have social justice elements as well.

I’m working on a book on conscious language, my most ambitious project. I felt strongly that as the one who coined conscious language for inclusive, empowering, and respectful language, it was my responsibility to share my insights and driving philosophy. I didn’t expect this book to sell at auction. Or that six houses would be bidding for it. I think it means the world is ready for my ideas.