by Calvin Yee 余威棋

Editor’s note: Bing Get Yee (1920-2010) was Charter Member #79 of the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California. He had an insurance business in Los Angeles Chinatown for many years. From a series of interviews, Calvin, his oldest son, compiled this story written in his father’s voice. Calvin was a technical writer in the San Francisco area. Special appreciation to Calvin’s wife, Cindy, and Calvin’s two younger brothers.

Early Days from Taishan to Detroit

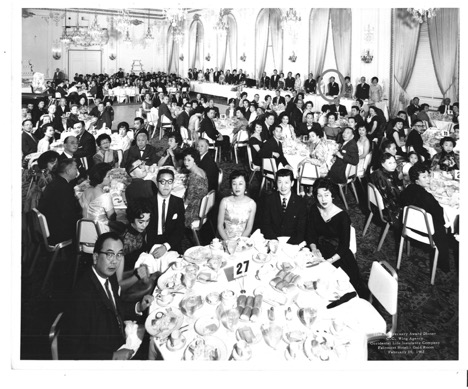

Photo courtesy of the Yee Family.

My Chinese name is Yee Weng Seng 余永盛. My English name is Bing Get Yee. I was born in East Little Canyon 東小峽谷 (Dong Xiao Xiagu) in Taishan, Guangdong in 1920. My first memory was my father carrying me as a young boy running through the bamboo forest. He was scratched by the bamboo leaves as he was running away from bandits. My father was a commercial seaman, and I rarely saw him at home.

At age seven, I was kidnapped by my older nephew. I later found out that he was angry at my parents for not lending him money. My nephew had a gambling problem. He took me out of elementary school and then drugged me to knock me out. When I woke up later, I was on a boat, not knowing where I was going. I protested vociferously, but it was of no use. My nephew was much bigger than me, and he kept me tied to the boat. When the boat docked, he led me to a small shed where I was locked up for a couple of days. While in the shed, I could hear the voice of my nephew haggling with a woman about money. It took me a while to realize that I was being sold to another family.

At the time, I didn’t know or understand that I had been “adopted” by another family who had lost a son in infancy. In those days of Old China, boys were prized over girls.

The family lived in Celkai 潮溪.[1] The woman who haggled with my nephew told me to call her Auntie. She let me go to school during the day but once I returned home, I had to do all the chores – sweep the floor, get water from the well, run to the hills to pick grass for cooking fuel, and plant rice in the fields. Auntie was a stern person. She’d scold me in a high-pitched voice that scared me to death.

This went on for about a year before Auntie told me that Uncle wanted me to come to the U.S. To prepare me for the interrogation by U.S. immigration officials, Auntie gave me a 40-page book to memorize. The book contained all the details of the Chinese village and the story of Auntie and Uncle’s family. To pass through U.S immigration, both my story and my uncle’s stories had to match. I studied the book for many months before Uncle sent for me. With the help of a local villager, I left Celkai village for Hong Kong. From there, I boarded a steamer for the United States. It took 18 days to finally reach Seattle, Washington. I was nine years old in 1929.

The U.S. immigration officials held me in detention for three weeks and interrogated me several times over that period. I was released but only because a Chinese man intervened and bribed the immigration official with money. I stayed with this Chinese man for a couple of months before Uncle put me aboard a train bound for Detroit, Michigan, which was where Uncle lived.

Once I arrived in Detroit, Uncle told me to stay with his nephew, Ben Kee, who was 16 years older than me. Ben Kee had started a new laundry and needed help. I was expected to do the laundry and go to school at the same time. It was challenging because Ben Kee expected me to sort all the dirty laundry before going to school, and iron or mend all the shirts after school. Most times, I would have to run to school because I was late from sorting the clothes. And if I got back late from school, Ben Kee would curse at me for up to a half hour. I was scared of him because his voice was loud, and the words he used were very dirty. This made it hard for me to work in the laundry.

Living in the laundry was also hard. There was no bedroom, only a partition for Ben Kee. I slept in the drying room, which was a room with a stove. I had to shovel coal into the stove and get the coals red-hot so the laundry could be dried. This was nice in the winter time but unbearable in the summer. I worked nine years in the laundry, and I hated every moment of it. I swore to myself that when I grew up, I would never work in a laundry again.

During this time, there was a lot of racial discrimination against the Chinese. I lived in a neighborhood made up of Polish workers. Most of them were single, and they would taunt me with “Chink, chink, Chinaman, sitting on a fence. Trying to make a dollar from 15 cents.” I got mad at them, but I couldn’t do anything because they were much bigger than I was. When I left school, I’d run as fast I could to get back to the laundry and avoid the taunts.

My only pleasure during my childhood was attending classical music concerts and taking black-and-white photographs.

When I turned 18, Ben Kee took me back to China. Ben Kee wanted to see his wife. He took me along because Uncle asked him to. This was in 1938. I was happy about going back because I might get the chance to escape working for Ben Kee, and I’d get the chance to search for my true parents.

Upon arriving back in Celkai village, Auntie told me that I had to get married before returning to the U.S. If I didn’t get married now, she said, I would forget about her family and never come back. Auntie tried to matchmake me with many ladies. But I resisted her attempts. This went on for over a month. Finally, one day, my uncle and I were returning home from another matchmaking session and stopped to rest at a teahouse. Out of the corner of my eye, I spotted a nice-looking young lady and stared at her for a long time. Uncle noticed and asked, “You like that girl?” I replied, “Yes.” Uncle said, “Consider it done.” He got a matchmaker to find out who she was, where she lived, bargained with her family, and a few days later, I was married to Pearl Wong 黄珠均 (1923-2022). She was 16.

But I couldn’t stay long in the village after my wedding. The Japanese were closing in on Guangzhou, and I had to leave or risk being stuck in China. With great reluctance, I had to leave Pearl back in the village. I escaped to Hong Kong by boat at night.

Upon returning to Detroit in 1939, I had to start all over again, and jobs were not easy to find. Over the next year, I worked in a laundry and as a waiter in a restaurant, but neither job was satisfying. At that time, there was a government program called the National Recovery Act (NRA), and it offered a job for fixing radios and electronics. I applied for the job and got it. I worked this job until the attack on Pearl Harbor.

World War II

After the attack, everyone got drafted. But I read an Army advertisement that said, “If you enlist, you can get the job you want.” I enlisted to do aerial photography. The Detroit Free Press was at my Army induction and took a picture of me. The next day I saw my picture on the front page with the caption “Yee go get a Jap.”

In January 1942, I reported for Army duty by boarding a train. The Army didn’t tell us where we were going. When the train reached its destination, I was dropped off at the Camp Grant Medical Center in Illinois. I told the sergeant that I had enlisted for aerial photography. The sergeant said, ”Take what you can get, Private! Now just do what you’re told!”

At boot camp, there were a lot of long marches, sleeping in tents during the dead of winter, and doing KP (kitchen patrol). But I kept thinking about what would happen to my wife if I die in service? She was only 20. The best she could do as a widow would be as a servant to some other family. That’s how it was in China then. So, I bought $10,000 of life insurance, hoping that this money would help Pearl and the rest of the family if anything happened to me.

After boot camp, I was shipped to Letterman Army Hospital in San Francisco for two months to train on anatomy and medicine surgery. After that, I was shipped again to Camp Callan in San Diego to learn surgical techniques at a field hospital. In March 1943, I was shipped to Camp White near Medford, Oregon.

In July of 1943, I boarded a train with thousands of other G.I.s, but I didn’t know where we were going. Five days later, the train arrived in New York City, and I was swiftly herded to board a big boat, staying in bunks that were ten levels below the deck. The boat left at night and again, I was not told of its destination. A few days later, the boat made its first stop at the port of Rio De Janeiro for fuel and supplies. Nobody was allowed offshore. The next day, the boat left for Capetown, South Africa. Again, no one was allowed offshore. After gathering fuel and supplies, the boat left for Bombay, India.[2] Once I arrived in Bombay, I was hurried to a narrow-gauge train. I spent seven days aboard the train headed for Chabua, a city in the northeast province of Assam. The troops stayed there for a couple of weeks. Then I was told to board a C-48 plane to fly over the Himalaya mountains and into Kunming 昆明, China. Our troop stayed for a couple of weeks before boarding a convoy of Chinese-built trucks and leaving town. Again, nobody told me where we were going. The road was all dirt and gravel – there was no asphalt or cement. It was very narrow, and one time, my truck nearly fell off a cliff because the driver couldn’t see another truck coming around the bend. Later, I found out I was on the Burma Road.

On the third day along the Burma Road, the trucks crossed the Salween River, which runs along the Chinese-Burma (now Myanmar) border. On the seventh day, my troop finally arrived in Poshan 坡山K.C. village, which is in the southern area of Guilin, China. That’s where my troop set up surgical tents to perform life-saving operations on G.I.s. On the days when there were battles with the Japanese, I’d be busy helping the surgeons during operations, cleaning out wounds that had maggots laying eggs in them because of gangrene, assisting the doctor with open brain surgery, taking shrapnel out, stitching up soldiers, and removing sutures. There were a lot of tough situations to deal with. For Chinese soldiers with gangrene, you either cut off their limbs or let them die. Many Chinese soldiers brought to the surgical tent yelled that they didn’t want to have their leg sawed off because in Old China, they would be a beggar for the rest of their life. It makes me want to cry – even after more than sixty years removed from the situation.

On non-combat days, I’d keep myself busy with shooting photographs and developing film. It did get lonely at times, especially when nobody would send you mail or letters. My wife, Pearl, didn’t write. I ended up writing mostly to high school friends back in Detroit.

I stayed in China until about March 1945. Right before I left the country, Uncle wrote to me that he desperately needed money. I had saved up $1500 from my Army pay. I sent Uncle all that I had.

In August 1945, the U.S. dropped the atomic bomb and WWII ended shortly thereafter. Because I had over two years of military service, I was eligible for a 30-day furlough back to the States. I took it and flew back to Fort Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania to receive my furlough papers. When I arrived at the Fort, the Army asked me if I wanted a discharge. I immediately said, “Yes!” I was ready to leave the Army after almost four years. But then I had another decision to make. The Army was willing to transfer all of a G.I.’s family from where ever they were in the world back to the U.S. at no charge. I was tempted to bring my wife Pearl from China, as I was lonesome for her. But I still wanted to go to medical school so I could return to China and help my people. My fear was that if I immediately brought over my wife, I’d have four or five kids, and I could not continue my education. That would doom me to just being a laundryman or a restaurant worker forever. I decided to go to college at Wayne State University and let my wife stay in China until I graduated. After that, I would bring her over to the U.S. or I would return to China.

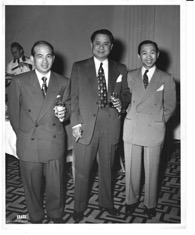

(Left to right) Louie Ong, K.C. Chow, and Bing Yee.

Photo courtesy of Calvin Yee.

Post-War Insurance Pioneer

The next few years were hard for me. I had to attend classes in the morning, work as a waiter at a restaurant during the afternoon and early evening, and study at late night. My grades as a pre-med student weren’t that good, and I realized I needed to switch to another major to graduate from college. In 1947, I switched my major to pharmacy. I was very poor, and my income from the restaurant barely paid the bills. However, a chance encounter at the restaurant would change my life.

One day, a Chinese man with a big top hat and a 9-seat Cadillac came into town to dine at the restaurant where I was working. His name was K.C. Chow. He lived in California, and he made road trips to sell life insurance. He worked for the first agency in the life insurance industry that hired Chinese salespeople, the C.C. Wing Agency of Occidental Life. While waiting on him, K.C. would chat with me about my life. Then he offered to pay me $10 a day if I would introduce him to my relatives. That was a deal I couldn’t refuse. I was only making $150 a month working full-time so any extra income helped. He sold a lot of life insurance policies to my relatives.

After a while, K.C. wanted to go back to California. He asked me to take over his business. I said, “I’m not a salesman, and I don’t want a full-time job because I want to finish pharmacy school.” K.C. replied, “Just sell insurance on the side. If you sell just one or two policies a month, you’ll make $100 as extra money. Try it first. You can always quit. It doesn’t cost you any money. All you need to do is take some lessons and take a state examination to get a license.”

I agreed, and I studied hard. I passed the state exam in 1947. I started selling life insurance while I was going to pharmacy school. On weekends and holidays, I’d go out to various laundries and restaurants to drum up business. For the first month, I didn’t sell any policies. In the second month, I sold one policy. By the end of the year, I made $500 selling insurance. It wasn’t a whole lot but it was extra money -which would help pay for a flight to bring Pearl over to the U.S.

I continued to sell life insurance until I graduated from pharmacy school in 1951. At that point, I brought my wife Pearl over to Detroit, Michigan. I was determined to open up a pharmacy. But my mentor, K.C. Chow said, “No. Try selling life insurance for a while and see how you like it. If you’re successful, then you don’t have to go back to pharmacy.” K.C. decided that we should travel the country to sell life insurance in different towns where Chinese lived. The commission split would be 60 percent for K.C., 40 percent for me. I agreed to it.

Over the next four years, K.C. Chow and I and would cover the entire U.S. from West Coast to East Coast, from the Midwest to the Deep South. During that time, Pearl gave birth to three children in Detroit and was taking care of them alone since I was traveling. But she yearned for a warmer climate similar to Taishan. Breaking ice on the sidewalk and shoveling coal into the furnace during winter were not appealing to her. I don’t blame her for wanting to move to California.

So out of consideration for Pearl, I reluctantly packed up our bags in 1956 and moved the family to the Los Angeles area. I had to start my business all over again as I didn’t know anyone in Southern California. My car was my office as I would spend 12 to 14 hours a day – weekends included – driving to prospective clients at their home or business. It took me about five years before I established myself and my reputation as a life insurance professional. From there, my business grew, and I made more money than a pharmacist. That’s when I quit renewing my pharmacy license and focused only on life insurance, estate planning and pension planning. When I retired in 2002, after 55 years in the business, I had served over 2,000 individual clients in the continental U.S. Along the way, I garnered these achievements for which I am proud of:

- Chartered Life Underwriter (CLU) designation. (The industry equivalent of an academic degree in insurance, 1966.)

- Chartered Financial Consultant (ChFC) designation. (The industry equivalent of an academic degree in financial planning, 1985.)

- Advance Estate Planning and Advanced Pension Planning, American College. (The industry equivalent of a graduate degree in insurance, 1980.)

- 6-time Qualifier for Top Club (between 1949 and 1963).

- 42 straight years as #1 Leading Producer for C.C. Wing Agency of Occidental Life (1952 – 1994).

- 25-time Qualifier for Leading Producers Club (between 1957 and 1994) which was a group of the top 100 producing agents in Occidental Life.

- 35-time Qualifier for the Million Dollar Round Table (MDRT) starting in 1965; only the top 5 percent of all life insurance agents in a given year qualify for this club.

- 20-time Qualifier for The Big “O” Club, special club by Transamerica Occidental for agents who qualified for MDRT (1974 – 1994).

- 45-time qualifier for National Quality Award (1956 – 2001). The premier life insurance industry award focused on recognizing outstanding performance for life insurance agents. The award is based on a sales person’s ability to keep the insurance policy they sold “in force” or Active. Nearly half of all policies lapse within 3 years.

Keys to My Success

My motto has always been “My job is to serve the community”. To get more business, I realized that I had to offer more than just the life insurance product. My ability to speak/write English was a crucial skill that attracted many potential customers. They asked me to translate at immigration hearings, or fill out immigration forms to submit petitions for their wives and children to come over to the U.S. I provided most of this service for free. My thought was if I charged them money, then they wouldn’t feel obligated to me. But if I didn’t charge them for my services, then they would feel obligated to buy insurance from me sometime in the future. Many waiters in the restaurants would pay an accountant $4 or $5 to file their simple income tax forms. I would help these people to file their tax forms without charging them. This strategy helped me get more and more business.

The other service I offered “unofficially” was being a matchmaker. In the life insurance, you not only get to know your clients, but also your client’s family and relatives. With that knowledge, you get to see who might be a good match or not. In my life, I’ve successfully matched over 35 couples whose parents were clients of mine.

In terms of community involvement, I am a charter member of the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California and a founding member and past president of the San Gabriel Chinese Cultural Association.

[1] Celkai 潮溪 in Taishan is also Chiukai, and Chaoxi in Mandarin.

[2] Now, Mumbai.