By George and Elsie Yee

Mr. Chung Wong, a produce man. Early 1900’s in old Chinatown. Courtesy Dorothy Siu.

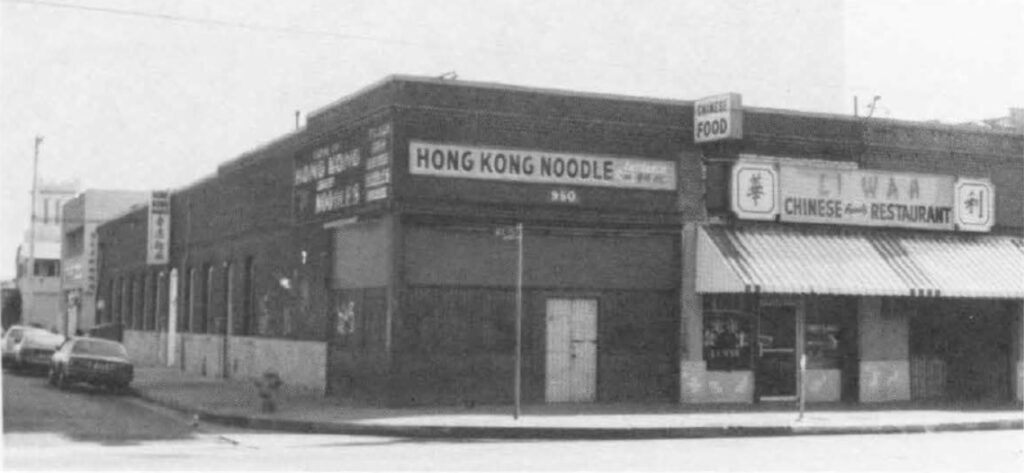

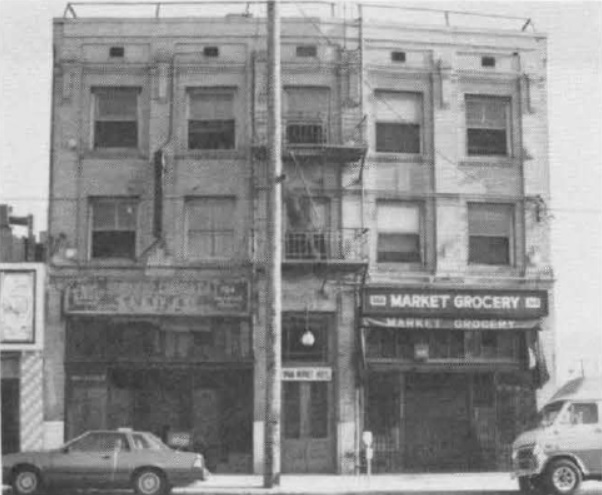

The City Market today.

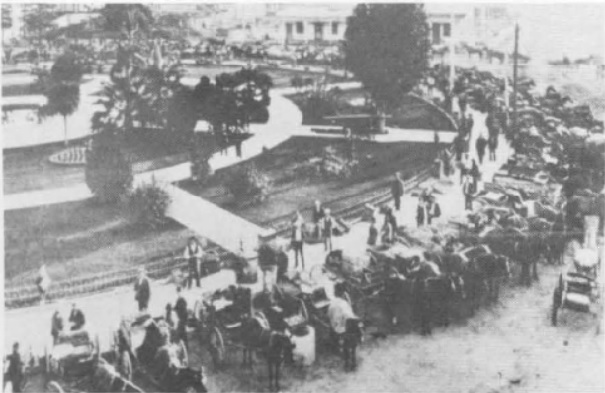

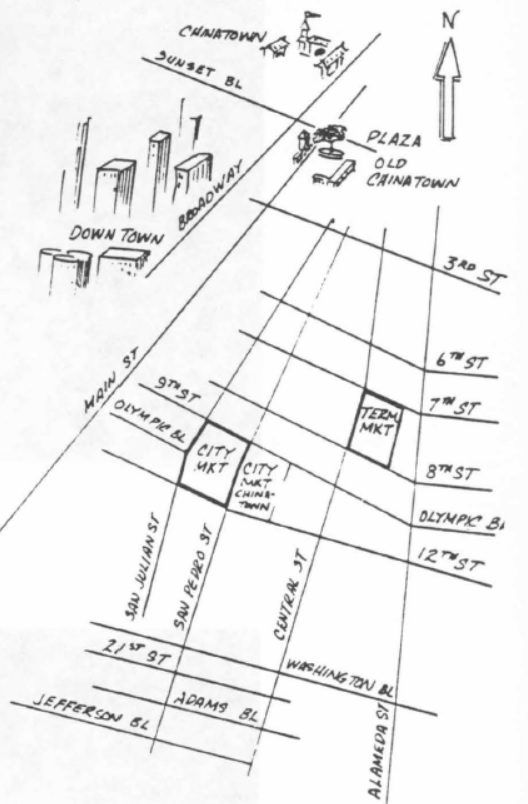

The first Market, at the Old Plaza, next to Old Chinatown, 1895. Courtesy of City Market of Los Angeles.

Louie Gwan.

Courtesy of Mrs. Victor Wong.

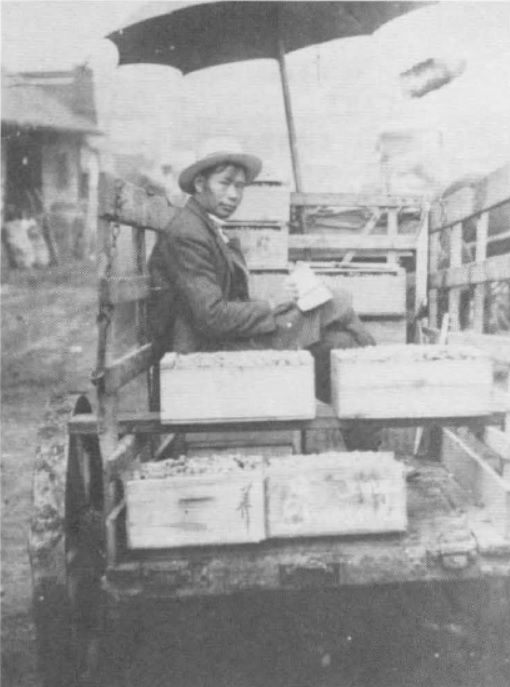

Vegetable peddler. Pre-1900. Courtesy of Los Angeles

County Museum of Natural History.

Chinese Historical Society of Southern California

Few Angelenos, outside of a few old timers in the wholesale produce industry, know the historical role of the Chinese in developing the industry and the City Market of Los Angeles. The story goes back to the 1870s. United States census shows only 172 Chinese living in Los Angeles in 1870. With the completion of the San Francisco to Los Angeles railroad link in 1876, in which 3,000 Chinese laborers were used, the sleepy city of Los Angeles started to boom. The number of Chinese also started to increase.

Most Chinese were employed as hired cooks, servants and operating laundries. A few were growing small patches of Chinese vegetables for Chinese consumption. As Los Angeles grew, the number of small Chinese farms quickly expanded to start supplying most of the vegetable needs of the city. These farms were scattered mostly through the southwestern section of the city along West Pico Blvd., Washington Blvd., and Adams Blvd.

Chinese neighborhood vegetable peddlers delivering from door to door with horse and drawn wagons became a common sight in Los Angeles, and continued to be for the next 50 years.

In 1880, 50 of the 60 vegetable peddlers in the city were Chinese. By 1894, 103 Chinese peddler wagons were registered in the city of Los Angeles. The importance of this monopoly was illustrated during the winter of 1878-79 when the city passed a new ordinance regulating vegetable vendors. The Chinese peddlers went on a protest strike causing a great inconvenience to the population. Recognizing the power of organization, the peddlers formed the Wai Leong Hong (Good People Protective Association) in 1879 as a welfare and protective organization to look after one another.

By the tum of the century, the Chinatown area, east of the Plaza, was becoming a busy place. There were close to 2,000 Chinese in Los Angeles with many living in the Chinatown area. The peddlers quartered their horses and wagons at stables nearby and the farmers brought their vegetables into the area to sell to the peddlers. The wholesale produce market business was coming of age. Soon the congestion of wagons around the Plaza forced the market to move to Third and Central Streets and then to Sixth and Alameda Streets in 1909.

Many of the Chinese did not like the arrangements at Sixth and Alameda Streets and looked toward building a new wholesale produce market at the Ninth and San Pedro Street area.

Louie Gwan, a wealthy Chinese produce dealer, was the pioneering promoter of this move. Handbills were passed out and meetings were held to rally the Chinese.

The Wai Leong Hong Association, which has become somewhat inactive during the years the market was at Third and Central, was reactivated to help raise money. Members of this association in later years served as the backbone in forming the Chinese Produce Merchant Association of Southern California.

Yee Mun Wong, Secretary

Chinese Produce Merchant

Association of So. Calif.

Two hundred thousand shares of stock were sold at a dollar a share to help finance the start of the market. Louie Gwan donated 1,000 shares to the market as a starter. In order to insure the success of the project, it was necessary to have the Japanese farmers join the Chinese move. Louie Gwan and other Chinese bought large shares of stock under the Japanese farmers’ names and gave it to them as a loan. This move gave the farmers an interest in the new market to entice them to leave the Sixth Street Market and bring their produce to Ninth and San Pedro Street.

Organization meetings were held at 398 S. Los Angeles Street and the name, City Market of Los Angeles, was selected for a new market. A 15-year lease was obtained on 6.7 acres bordering Ninth Street from the Huntington Land and Improvement Company for $230,000.

The City Market Articles of Incorporation, dated April 13, 1909, listed the following as shareholders:

158 Chinese holdings; 40,885 shares

65 Japanese holdings; 35,150 shares

19 Caucasians, four big shareholders held 10,000 or more shares.

The corporation officers were Frank Simpson, Ho Lee, S. Shibuya, Sl Hillkowitz, and Larry Zaiser.

Walt Fleming, President

and General Manager of

City Market

Louie Gwan did not speak good English, so he did not want to hold office. Ho Lee was selected instead. Because the law ( Alien Land Act) forbade Chinese from owning land at that time and to avoid possible future problems, the Chinese voted as a block to elect a Caucasian, Frank Simpson, as president and to elect Ho Lee as vice-president.

Yee Mun Wong

Eventually, all 20,000 shares of stock were sold. The Japanese Farmers Association recorded the final shares with distribution as follows:

373 Chinese holdings; 81,850 shares

94 Japanese holdings; 36,250 shares

45 Caucasian holdings; 81,900 shares

Construction of the first three buildings was started on April 24, 1909 and completed on July 31, 1909. One building bordering the south side of Ninth Street, two others paralleled San Julian and San Pedro Street, south to Olympic Blvd., forming a horseshoe- shaped market. There were 89 inside house stalls and numerous yard stalls. During the construction period, the produce dealers and farmers did not pay rent. After completion, the inside stalls were partitioned to accommodate 44 wholesale produce dealers occupying one or more stalls. Of the 44 dealers, 20

were Chinese.

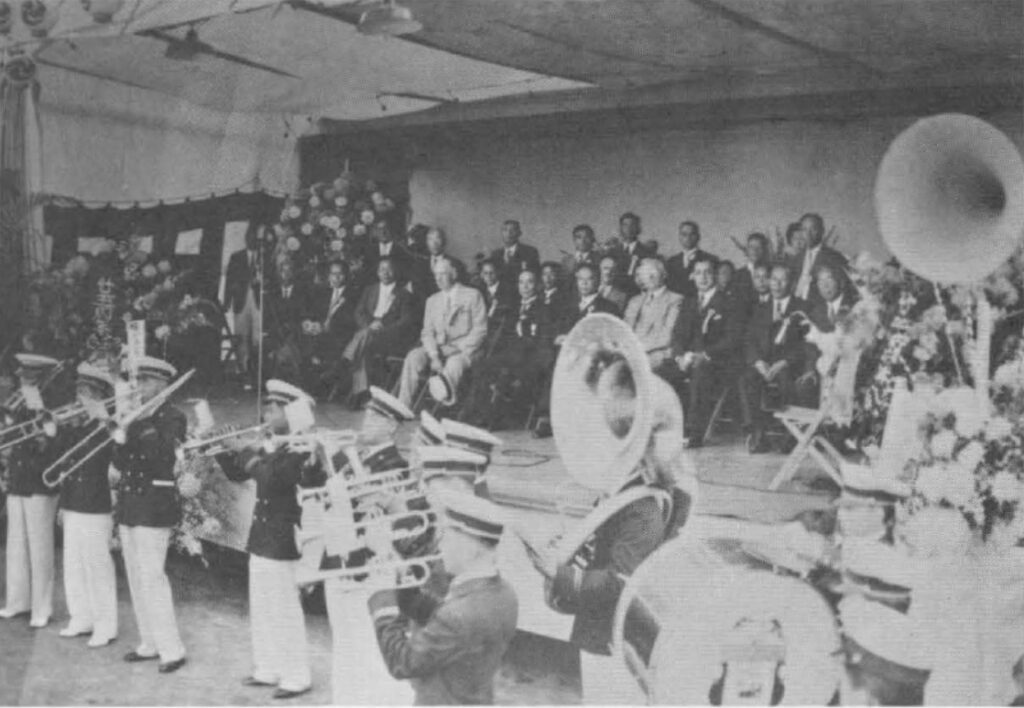

When the market opened on August 17, 1909, a 10-year lease was offered. An inside building stall measuring 10 x 40 ft. was rented for $8 per month for the first 3 years, $10 for the next 4 years, and $12 for the final 3 years. Yard stalls, measuring 8 x 25 ft. rented for $1 per day or $25 per month. Although the rent for an inside stall increased steadily through the years, the yard stall remained about the same into the 1950s. One of the reasons was that a yard stall could be rented again the same day whenever the space was vacated.

Many Chinese squatters and farmers operated from the yard. Most were small farmers or second jobbers who were breaking down the produce crates into smaller lots for resale to the small stores and restaurants. There was a market ruling requesting dealers renting only yard stalls to limit their produce handling to those grown within a 50 mile radius. Thompson seedless grapes were selling at 50¢ a crate. Celery shipped in from Santa Ana and Fullerton sold at 60¢ per dozen. Cabbage sold for 50¢ a sack in 1909.

The early pioneers brought other members of the same clan or people from the same village into the industry. Chinese with Louie and Woo surnames were prominent among produce dealers and farmers.

The Chinese influence peaked in the 1910s with the Chinese dominating both the supply and the distribution of farm produce. Close to 300 Chinese were working in the market. The total number of Chinese-owned produce houses including those occupying yard stalls was about 100. Some Chinese became prosperous.

There is a story told of a Chinese by the name of Quan who threw a big birthday party that went on for 3 days. The Mayor of the City had to come down to tell the Chinese to go out and cut the vegetables because there

were no vegetables to be sold in Los Angeles.

Dan Louie

Produce Dealer

On December, 1910, the City Market declared its first stock dividend of 3¢ a share.

A few years after the City Market opened, a number of the Japanese farmers to whom Louie Gwan gave stock, failed. The loss was devastating for Louie Gwan. He went broke and never recovered from this loss. The City Market gave him a pension of $25 a month. The years he lived at the Bow On Association headquarters at 512 East 11th Street. He passed away in 1955.

In 1918, the Southern Pacific Railroad built the Terminal Market at Seventh and Central. The Sixth Street Market moved

there. In a few years, many Chinese produce dealers were also operating out of there, but the bulk was still at the City Market area.

Most of the produce business was with non-Chinese customers because there were very few Chinese grocery stores and slightly greater than a dozen Chinese restaurants in Los Angeles in this time period.

Large sections of the Los Angeles area were still open fields. Over 400 Chinese were engaged in farming in and around the city of Los Angeles.

Grandfather farmed near Adams St. and Western Ave. Father used to go up to see Mr. Bullock (the department store owner) because he rented ground from him. As the city grew, he moved further out near where Hughes Airport is now. The Chinese complained that the area was too swampy. The owner offered to sell the land to the Chinese, but the Chinese turned him down because they couldn’t own land at that time.

Dan Louie

There were farms in San Fernando Valley, Compton and Vernon. Workers were recruited from Chinatown. They lived on the farm while working. During the off

season, the workers found other odd jobs – maybe in a laundry.

William C. Chan

Produce Dealer

The Chinatown of L.A.

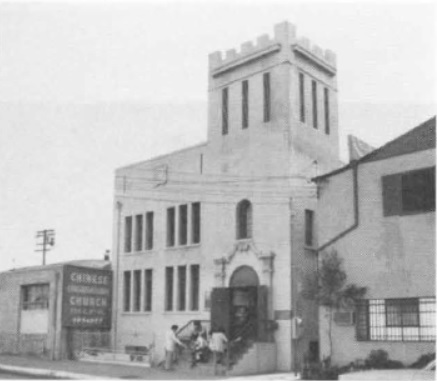

The Chinese Congregational Church on 9th Place, erected 1924.

The Market Hotel building, erected 1915.