By Paul G. Chace

Paul C. Chace, a native of Los Angeles, is a member of the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California. He is a historian, an archaeologist, and head of Paul C. Chace & Associates, a heritage planning firm.

Delivery of the mail in Los Angeles’ early Chinatown was a special challenge, for “Little China” was a community within a community. This ethnic enclave with its distinctive languages and cultural traditions required an extra-ordinary adroitness from the European-American mail carriers of a U.S. postal service that had long maintained a proud tradition of outstanding delivery service. The specialized services the U.S. Post Office provided to cope with the mail of the Los Angeles Chinese community were noteworthy, and the details were set forth in a news article authored by J. M. Scanland. The story, reproduced below, was recently rediscovered as a clipping from the Los Angeles Times of October 21, 1906. ( The publicly available microfilmed copy of this particular Sunday issue of the Times does not include this article; but the “Sunday Magazine” supplement section is not preserved with this microfilmed issue, and it is presumed that the original article was published in the magazine section.)

Scanland provides some interesting details on the U.S. Post Office’s special efforts to provide mail service to the Chinese community in Los Angeles. His article focuses on the form of the mail service ( address interpretation, distribution, and delivery) and certain postal etiquettes and customs of the Chinese. The details in his story indicate that Scanland had secured the information for this article from a very knowledgeable source.

While documenting the mail service in this article, Scanland also touches upon a number of topics of broader interest; for instance, he mentions that the Los Angeles Chinese community in 1906 was remitting a total of about $35,000 each month back to relatives in China through the Postal Service. Unfortunately, he does not indicate its source for this important and quite specific statistic. It probably was Postmaster Flint himself, and the Postmaster would have been in a position to know. Scanland specially states that this amount was sent “through the post office.” Forty years later, in mentioning the mail carriers in Los Angeles’ Chinatown, Liu ( 1948: 39) states that when the then elder men were younger they sent “money orders” remittances and infers that they were Federal postal money orders. However,

the $35,000 amount Scanland mentions probably does not include funds remitted through private bank channels. During the 1890’s the private Farmers & Merchants Bank was the bank closest to Chinatown, and whenever a steamer was sailing, they issued up to 25 drafts a day for Chinese on their correspondent bank in Hong Kong (Cleland and Putnam 1965:65 ). The Farmers & Merchants Bank was only one of four private Los Angeles banks that were involved with the Chinese community and were advertising in the Wah Mi Sam Po weekly newspaper published in 1899 in Los Angeles. Several of these banks continued to advertise in this Chinese community newspaper _when it became a

daily, published out of San Francisco the following year as the Chung Sai Yat Po (from newspaper reproduction in Mansie Chew 1940). Although the circle of Los Angeles bankers remitting exchanges to their correspondent banks in the Orient would have had a good general idea of the total funds transferred, information would have been kept private. Also Chinese remittance shops utilizing personal couriers to deliver private funds to rural villages in China operated locally, such as the remittances operation run by the merchant Wong Sai Chee in Riverside (Huang 1985). Lastly, the emigrant families interviewed in China by Mei (1984:57) stated that remittance payments were most often made by “checks” that were cashed at banks or stores. It is probable therefore that those funds remitted through private channels would have added to the Post Office’s $35,000 figure, and the grand total being remitted from all the Chinese in Los Angeles would have been a greater sum.

Scanland also indicates that in 1906, the Association that managed the community affairs of Chinatown was composed of seven District Companies, and the Association had a headquarter building. (A few details on the histories of these local District Companies, their Association, and their activities in Los Angeles is provided in Chen 1952:226-254, and also briefly in Lui 1948:101-107. However, the evolution of these groups in Los Angeles has never been specifically set forth historically.) Chen determined that Los Angeles used to have six or seven district organizations, but by the 1940’s only one still maintained a headquarter building, although several others existed in name only. The functions of the district associations have changed over the years and were eventually shifted over to The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association.

It is somewhat surprising that the Chinese community in 1906 was receiving “a great many” Chinese language newspapers. The first Chinese language newspaper published in Los Angeles was the Wah Mi Sam Po, a weekly newspaper edited by Ng Poon Chew which started in May 1899. It was curtailed before the year’s end to be replaced by the first Chinese language daily newspaper in the United States, The Chung Sai Yat Po which was published in San Francisco beginning February 1900, also by Ng Poon Chew who had moved north from Los Angeles ( Chew 1940). Chinese language newspapers had been published in San Francisco since 1854. Scanland infers that by 1906 a number of different newspapers were being published and distributed to Los Angeles and throughout the United States from

various Provinces and towns in southern China. He may have been in error as to the origins of many of these papers, for they may have been those published in San Francisco. In any case, Scanland’s statements suggest that the community in Chinatown had a broader rate of literacy in its primary language and also that it was more concerned with news stories about Chinese political and cultural events than might have been otherwise apparent.

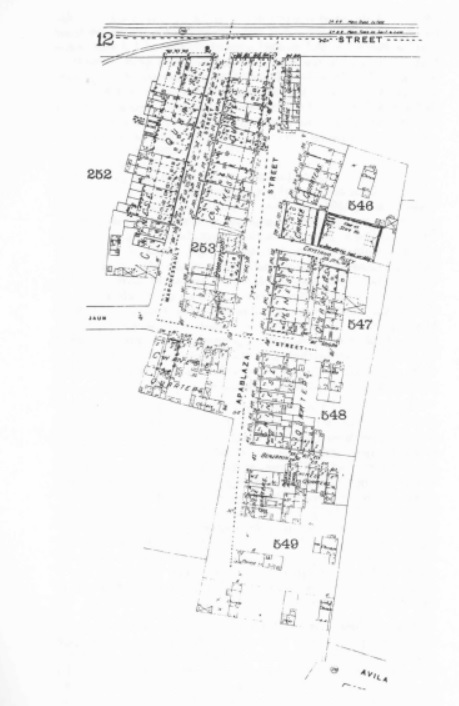

Scanland states that throughout Chinatown the streets were named and the houses had postal numbers. Figure 1 is a map of Chinatown in 1894, the “new” Chinatown area leased and developed on property on the east side of Alameda Street after the disastrous fire of July 1887 which swept through the area of the previous Chinatown located around and south of the Plaza. Although Chinese businesses still occupied the city blocks around the old Plaza after the fire, the new and distinctively Chinese area of development was apparently more often· referred to as Chinatown. Nora Sterry describes this same Chinatown east of Alameda Street after it was even more intensively developed (Sterry 1922) and states that the principal lanes were recognized by the postal authorities. Sterry’s description of Chinatown is

worth repeating as it gives some indication on the nature of the postal carriers’ routes through Chinatown.

“There are only two streets in Chinatown. They are the only streets with any sort of paving. There are, however, thirteen thoroughfares which are commonly recognized as streets, both by the Chinese and by the postal authorities. Some of these so-called streets would be extremely hard for the uninitiated to find. At one end of China Alley, entrance may be had from an inconspicuous gate and down a block-long lane, walled in on one side by a windowless brick building and on the other side by a six-foot wooden fence, or direct from the Southern Pacific yards by pushing open a hinged panel in this same fence, not to be distinguished at sight from other panels. At the other end it is necessary to approach through a narrow runway between the houses; this is not over three feet wide, is roofed over and turns five corners in the course of a few feet.

“Besides these thirteen streets, several of them only wide enough for pedestrians, there are at least twenty-two passage ways between the houses, most of them open to the sky, a few even being paved with stone, like the sidewalks which border the main thoroughfares. They are used by the Chinese as commonly as are the streets. There are several houses so situated, however, that there is no entrance whatsoever to them except through the house of another or by climbing a fence.”

J. M. Scanland, “A SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR,” the author of this 1906 article, used just his initials for his given names most of the time but he must have been John Milton Scanland, a western newspaperman and a free-lance writer. The only time the full name appears is in a small book he authored and published in 1908. Apparently he had two purposes in presenting this story about the mail service. First, as a professional, writing was his occupation and selling stories contributed to his livelihood. Second, and more important historically, Scanland was making another small but respectful attempt at creating an enlightened cross-cultural understanding of the Chinese community amongst English speaking, European-American readers. Scanland had a special inquisitiveness, an empathy, and a long-standing concern with the Chinese in the West. This special interest is most clearly reflected in the fact that of the seven published articles under his name, that are now known, six are about the Chinese. Although Scanland will rank as an important historical chronicler of the Chinese, knowledge of his career and personal history remains obscure. In 1894, as a young newswriter he was assigned to cover a riot situation in Los Angeles’ Chinatown (1926). He was listed as a resident and a “journalist” for several years in the early 1890’s in the Los Angeles City Directories, but was gone by 1895. He subsequently published an article on Chinese migration (1900) which he submitted from Cripple Creek, Colorado. He probably was related to the Scanlands listed in the local Directories as residents of Victor, a sister city of Cripple Creek. His next known published articles were on Chinese business methods in San Francisco (1904) and on Chinese literature in San Francisco (1906). By the early 1900’s Scanland had returned to Los Angeles as a “newspaperman” and his name appeared again as a resident in the City Directories, but he had left by 1906. Thereafter, he assembled a journalistic style booklet on the life of Sheriff Pat Garrett of Las Cruces, New Mexico, the man who shot “Billy, the Kid.” The book was published in nearby El Paso, Texas, in 1908 (and reprinted in 1952 with the statement that Scanland was a New Mexico newspaperman; however, Leon Metz, another published authority on Garrett claims that Scanland was “an El Paso newspaperman.”). Much later, by the early 1920’s, Scanland was back in Los Angeles and listed as a “newspaperman” in the City Directories, and he published two signed articles lamenting the fading exotic color and the decline of the Chinese “quarters” (1923 and 1926). Scanland’s name does not otherwise appear in the compiled bibliographies and indexes covering the history of Los Angeles, the Southwest, or the Chinese in California. A thorough search of Western newspapers might well reveal other identifiable Scanland writings. In any case, for historians, Scanland’s known publications distinguish him among the ranks of the earliest chroniclers of Los Angeles’ Chinese community.

The 1906 Scanland article on the Los Angeles postal service was rediscovered in the recent gift of the “Ng Poon Chew Collection” to the Asian American Studies Library at the University of California, Berkeley. This gift was presented to the Library by Mr. and Mrs. Lee Ruttle, a daughter and son-in-law of Ng Poon Chew. Dr. Wei Chi Poon, Head Librarian, courteously permitted a review of this new gift and allowed the copying of the article even though the collection had not been formally catalogued. The article is pasted in a file book of newspaper stories about Chinese from a variety of Western American, English language newspapers which had been clipped and labeled by professional clipping services. Apparently, Ng Poon Chew, as the Editor of the Chung Sai Yat Po in San Francisco, had received and mounted these clippings for his newspaper background files. These are two such clipping file books in the collection, and the clippings cover several years. Apparently these clipping file books had been saved and maintained in the Ng Poon Chew family until their recent presentation to the University.

References:

Chen, Wen-Hui Chung

1952

Changing Socio-Cultural Patterns of the Chinese Community in Los Angeles. Ph.D. dissertation, University ofSouthern California, Los Angeles.

Chew, Mansie

1940

Special Magazine/Book to Commemorate the Fortieth Anniversary of Chung Sai Yat Po. Undistributed typeset pages, copy preserved by Thomas W. Chinn, San Francisco.

Cleland, Robert Glass and Frank B. Putnam

1965

Isaias W. Hellman and the Farmers and Merchants Bank. The Huntington Library, San Marino.

Huang, Kai-Loo

1985

Presentation interpreting a Chinese letter in the Museum collection, Chinese Symposium, 18 May 1985, Riverside Municipal Museum, Riverside, California.

Liu, Garding

1948

Inside Los Angeles Chinatown. Printed in the United States of America.

Mei, June Y.

1984

Researching Chinese-American History in Taishan: A Report. The Chinese American Experience: Papers from the Second National Conference on Chinese American Studies ( 1980), pp. 57-61. The Chinese Historical Society of America and the Chinese Culture Foundation of San Francisco, San Francisco.

Scanland, John Milton

1900

Will the Chinese Migrate? The Arena. Vol. XXIV, No. 1, pp. 21-30; July 1900. The Alliance Publishing Co., “Life” Building, New York.

1904

Chinese Business Methods in San Francisco. Bookkeeper and Business Man’s Magazine, Vol. 17, pp. 1068-1081. Detroit.

1906

Chinese Literature in San Francisco. Book News, Vol. XXIV, No. 286, pp. 715-717; June 1906. John Wanamaker, Publisher; Philadelphia, New York, Paris.

1906

The Chinaman’s Mail. The Los Angeles Times, October 21, 1906.

1908

Life of Pat F. Garrett and the Taming of the Border Outlaw. Published by Carlton F. Hodge, El Paso, Texas. (Reprinted in 1952 by John J. Lindsey of Colorado Springs, Colorado.)

1923

Chinatown’s Fading Local Color. Saturday Night, Vol. 4, pp. 20- . Los Angeles.

1926

Quaint Chinese Quarter Doomed by Civic Center, History of Celestial Quarter Filled with Weird and Tragic. The Los Angeles Times, Part II, pp. 9-11; May 9, 1926.

Sterry, Nora

1922

Housing Conditions in Chinatown Los Angeles. Journal of Applied Sociology, Vol. VII, No. 1, pp. 70-75; November-December 1922. Los Angeles.