Eugene Moy

Editor’s note: Eugene Moy was an urban planner for the City of El Monte. He is a longtime leader of the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California, Chinese American Museum, and Chinese American Citizens Alliance. This is as told to William Gow on March 25, 2022 by Zoom and edited by Samuel Yee.

Mixed Beginnings

My dad always felt that he was an immigrant as he was born in China. But my dad was an American citizen because Grandfather was a citizen. My grandfather got his citizenship in 1890 under one of the habeas corpus cases. Grandfather was able to establish a laundry business in Montana, and my dad came over as a son of a citizen.

When I was born in 1949 at the French Hospital, New Chinatown was still fairly new.[1] Most of the Chinese American residential population was scattered, beginning with their displacement in the mid-1930s when old Chinatown was demolished for the train station. People moved into what is now present-day Chinatown, Lincoln Heights, Boyle Heights, and other communities. My dad had a grocery store in South L.A. at 105th and Main, which was then a semi-rural neighborhood southwest of the Watts area. We lived in a little two-bedroom house behind the grocery store. The family eventually expanded so there were four kids in a 650 square feet space. I slept in the dining room alcove; my little brother slept in my parents’ bedroom; and my two sisters slept with my grandma in the second bedroom. From that point on, I always had this comfort level of being able to sleep anywhere.

My dad shared his store ownership with two other families. There was Paul Wong and his kids who were right in the neighborhood. And then my uncle. Basically, you had one little grocery store that’s probably 1500 to 2000 square feet providing income for three families. This was the formula that often happened. Whether it’s Cambodians buying a donut shop or Indians buying a 7-Eleven, you get together with family or friends and pool your money together. You have a partnership, and you build up the business. If you do well enough, you then go off on your own. Eventually, my dad sold his share of the store and bought his own in Inglewood called Moy’s Market, a corner neighborhood grocery store that he ran with my cousin.

In the early to mid-1950s, you saw the Lassie show and the Ozzie and Harriet show on TV. You had this image of what the “American family” should be like. We didn’t participate in a lot of the mainstream social activities. I didn’t go into the Scouts, didn’t go into Little League. My parents stressed the importance of staying together. We could see that some of our neighbors go off to college somewhere far away, or join the service, or just move, but my dad always wanted us four kids to stay together. I knew that my parents tried to imbue in us the importance of maintaining the family unit.

In 1963, the Rumford Fair Housing Act was passed by the California state legislature. It had been common practice by real estate people to not sell to Black people or other ethnicities, so Rumford opened up other communities, communities like Inglewood or Lynwood or Compton, which previously had been very restricted. We were blockbusting. A well-known Japanese American real estate company, Kashu Realty, was taking advantage of the fact that race restrictions were struck down. The Crenshaw area was opening up, and a lot of Chinese and Japanese families were starting to move in.

We moved to Inglewood, and I went to Morningside High. I graduated in 1966, and in my class of 460, there were probably fifteen to twenty African American kids. When my little brother graduated three years later, his class was majority Black. People like our family, Black families, Mexican American families were moving in. My friends were Jewish, Armenian, Mexican American, and I had several Black friends. It was a mixture.

Of course, there was a lot of racial tension that was growing. My dad was concerned, like a lot of Asian American families, about the growing Black population. If you were operating a small business, the likelihood of getting held up by a person who was African American was greater than being held up by a person who was White. It was partly a function of the neighborhood demographics and partly a function of being an outpost in a growing Black community. After World War II and the Korean War, there was a lot of awareness of Asians being the enemy. That was in the news all the time, and we were aware of it. People would come into the store and say, “You dirty Japs” and other little curses at us as they put their money down for their beer or cigarettes. We understood that we did not appear to be the mainstream image, but we didn’t necessarily have that sense of a true Asian American identity. That didn’t emerge, at least for me, until the late 1960s.

Transitions

I joke with people that it took me eight years to get my bachelor’s. I was a physics major at the beginning, but after knocking my brains out for a few quarters, I realized that I just wasn’t smart enough. A part of it was because I was working a lot. I commuted from Inglewood to UCLA, and then I would come home and work in my dad’s store. At that time, you also would hear about the social movements that were growing, whether it was free speech or Black consciousness. Even in high school, I got to see everything close up. You could see Stokely Carmichael. You could see Angela Davis. You could see the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and all of those movements swelling up around you. I ditched classes, and I sat and watched on Bruinwalk and other speaker platforms. I remember seeing Warren Furutani speak. I wanted to help my yellow brothers, but I couldn’t understand how activists supported themselves. How could they go to Washington, D.C.? Where could they find the time to march in Westwood when I had to go to work? Maybe it’s that I grew up in a family business, having that responsibility to first survive economically and put food on the table. To people who went to rock concerts or music festivals, I would say, “Where do they get the money? How do they do that?” I was more driven by a practical survival instinct than a high-level idealism.

It was not until I transferred to Cal State Long Beach and moved out of the house that I got away from having this regular responsibility of going to the store from 5:00 to 10:00 pm or working the whole weekend on 14-hour shifts. I started looking at other jobs and developing other interests. I changed my major in 1968, ultimately ending up with geography. In 1969, I started working for the Long Beach Public Library. I said, “Oh, it’s cool. I could work in a library. I love books.” When you’re eighteen, nineteen, you’re full of energy; you can do everything, so you do a lot of things. One of my assignments was to work at a place called Rancho Los Cerritos, which the Long Beach Public Library system operated. This historic house museum was open to the public, and it did educational tours about California history. I learned about the fact that there were Chinese workers in the 1870s and 1880s in Long Beach, which was really interesting to me.

I didn’t participate in the Asian American movement activities at the time, but I did help with the emerging Asian American studies program at Cal State Long Beach. There were a number of protests, marches, and demonstrations. I was working while still taking classes, so I didn’t have a lot of time, but I do remember going to a couple of group events where we helped make posters for protests. You had a staple gun, and you stapled boards onto a stick.

I was really focused on social justice, community justice. When the Watts Riots occurred in 1965, my dad’s store was three blocks from the westerly line. That’s where the police barricades and everything else were. You could see the smoke in the horizon. It made me ponder, “What’s wrong with our cities?” That’s probably what led me to the urban studies program at Cal State Long Beach, a follow-up to my degree in geography. I wanted to get involved in historic preservation because I had already been interested in L.A. and Long Beach history and was still active in various Long Beach-area activities. A part of my urban studies interest included historic architecture, and I worked with two historic preservation groups in Long Beach. We started one organization to protect the downtown area, and we participated in another foundation that was developing an inventory of historic places in Long Beach. Later, I wanted to do the same thing in Chinatown, which merged my geography background with placemaking. At that time, there were historians who were really building on that concept of placemaking, especially for the ethnic enclaves in the state. My having had some education in urban studies basically led me to want to find a level of justice – whether social, economic, or political justice – and just find peace in our communities.

Snapshots

One day, I saw a little ad in the L.A. Times saying there was a meeting of the Chinese Historical Society. I said, “Oh, that sounds really interesting. I think I’ll go and find out what this is, learn what this is all about.” I had actually become involved in the Long Beach Historical Society in the 1970s, and learning about this history that there were Chinese early on was intriguing to me. I don’t remember much of my first meeting, except that it was very welcoming. We had the Yee brothers, historians like Bill Mason, and other people who seemed knowledgeable. Bill Mason had spoken to us in Long Beach; he talked about the Chinese and Japanese of Los Angeles. He was a real advocate. I said, “Oh, this aligns with my interests and what I’ve been doing: Long Beach history, L.A. history.” That was in 1976, the 100th anniversary of the completion of the western Golden Spike. We interacted with the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society to fund a monument, which still stands. We also had the Lang Station Preservation Monument in 1976, and we started Gum Saan Journal in 1977. Just being in regular contact with people like Bill Mason, Paul Louie and other people was inspirational. You had a large and diverse group of people who really were good advocates for preserving history, and oral histories were definitely an important part of that preservation effort.

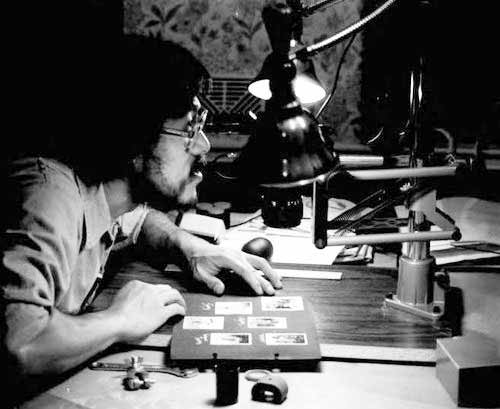

Eventually, we started going to the L.A. Public Library to look at historic newspapers because we didn’t have a large database of information about the Chinese in L.A. “Why don’t we go through all the newspapers and copy all the newspaper articles that we can?” One project led by Paul Louie and a couple of other people was going into the L.A. Public Library archives and photographing these gigantic volumes of newspapers. I had taken photography before and had a copy stand with a good 35-millimeter camera. That was around 1977 or 1978. We had an awareness of this lack of information, and this growing identity really helped with our self-esteem. We realized that history needs to be written in a way that makes up for the previous erasures.

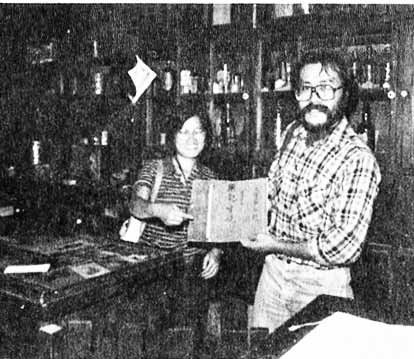

CHSSC’s First Book

I have to give credit to all the authors of Linking Our Lives. If you look at that back cover and you see all the people involved, whether it’s Lucie herself or people like Susie Ling, Suellen, and Judy Chu, all of these were women who were getting their degrees and really had rich material from the interviewers to work with. The technology, at the time, was cassette tape recorders and typewriters. We heard presentations by various people about oral history. I didn’t really get involved in the actual initial interviews themselves, because the Asian American Studies Center had a couple of people who were paid to work with the program. I became more involved in the follow-up phase as a part of the editorial committee, where I worked on the summaries and the publication of the book. I would listen to the tapes and then transcribe the recordings. One of the recordings that I transcribed was with Rodney Chow, who grew up in the City Market area. He talked about his knowing Abe and George Chin, the brothers whose father was Chinese and mother was Black. He would say, “Oh, yeah, I’d see them in the restaurant; these guys looked Black, but they could speak Chinese. Damndest thing you’d ever see.” These kinds of comments would stick in your mind.

“So, how were we going to get the story out?” We had a goal of really making it available to the schools. It was really about public education. We actually sold quite a few books at the beginning, mostly at the college level. It definitely was seen as a teaching tool to be able to spread the word. Today, I think that we’ve achieved a certain level of influence through reclaiming some of our history. Before, there was an almost naive youthful energy in wanting to do things. Now, we have the ability to actually do it and get it done. It’s hard to believe I was president of the Society forty years ago.

Retrospection and Reclaiming History

My dad passed away in 1979, when he was only 72 years old. At that time, I realized I had not talked to my dad enough. Even though I spent time at the store, he was never a person who talked about his early life. Now, for the last forty years, I’ve been trying to recreate more of his life. I know more about his history than I ever did. It was our group’s awareness that it was important to try and preserve the history, the stories, the speakers from the past. People in my generation don’t feel the need to elevate our prestige, partly because we feel that we are now part of the mainstream or are more accepted. We don’t find the same barriers that our parents’ generation felt. But we want to create a record and add our presence.

We were working towards projects like the creation of the museum in the site of old Chinatown which would recognize our historic past and maybe be a place to share with the larger community. When we were forming the Chinese American Museum organization, we had meetings with various people, including the founding executive director of the Japanese American National Museum, Irene Hirano. We asked her, “Why are you doing what you’re doing?” And she said, “We want world peace because of what Japanese Americans had experienced, such as internment and the anti-Asian hate.” Those kinds of words stick in your mind and definitely have a bearing on what you continue doing. Therefore, we shouldn’t limit ourselves to just Chinese American or Asian American history, but also the network or the interactions that were created in history. Today, there are many members who are interested in knowing about our history and connecting and networking. The Society switching to monthly Zoom meetings during Covid has enlarged our audience, which is terrific. People from Canada or New Jersey have sent comments saying, “This is terrific what you’re doing. We want to join.” People love hearing about this because they want to learn. People want to hear about the connections that we had and have.

In the end, history should be written by everyone, not by just an exclusive group of scholars. We’re all a blend of something. For those who say, “I’m all Chinese,” but what does “all Chinese” mean? Might you have Mongolian blood? Do you have Burmese blood? We interacted with Arab, Italian and Jewish traders in the 12th to 14th centuries. What good are these nationalist identities when we’re much more global than we have ever been? These days, you see narratives that say Chinese American history began in 1848 with the Gold Rush; our arrival began much earlier. It didn’t start with one event; there were many interactions in history. Our history is more than 500 years in the Americas, not just 160 years in California.

[1] The French Hospital was established in 1860 during a small pox scare in Los Angeles amongst the French population. It boasted a Joan of Arc statue on its lawn facing Castelar Elementary on College, just west of North Hill Street. It was later renamed Pacific Alliance Medical Center. The Chinatown hospital closed in 2017.