Marjorie Lee

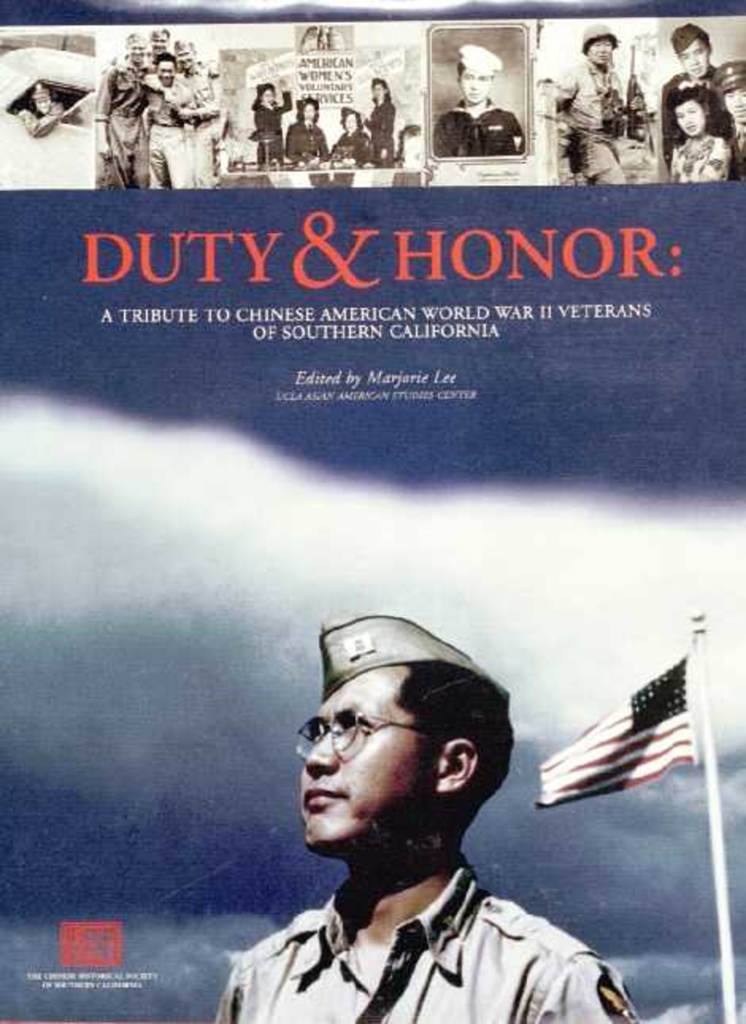

Editor’s note: Marjorie Lee was one of the authors of Linking Our Lives. She is library coordinator, information specialist and archivist at the UCLA Asian American Studies Center for 35 years. She is the editor of Duty and Honor: A Tribute to Chinese American Veterans of World War II in Southern California (CHSSC, 1998). Lee has been recognized as LUAC-LA 2009 Librarian of the Year, 2022 Chinese American Museum Heritage Keeper Award, and 2022 PBS SoCal and KCET Southern California Local Hero. This is from an interview with Susie Ling on August 17, 2023 in Monrovia.

My Family Background

I was born at the Queen of Angels Hospital in Los Angeles. My family was then living in East Hollywood but we moved to the San Gabriel Valley in 1960. Dad did not want to raise his family in Chinatown. My parents couldn’t afford Monterey Park, so we lived just south of the Pomona Freeway. Montebello wasn’t as cool as Monterey Park (laughs). At that time, Dad owned a small fruit and produce distribution company in Los Angeles near City Market and, with his cousin, worked long hours from midnight to noon on average to sustain the business. Dad thought it was not that successful, but enough to save money and buy the family’s first home. Dad even prioritized planning and taking road trips with his family.

Dad was born in Toisan (Taishan) and immigrated alone when he was twelve years of age. His father, already in San Francisco Chinatown, sent for him. Dad was detained on Angel Island for twelve days. Dad grew up cooking for his uncles and his father in between his schooling. When he was about thirty, he went back to China to marry. He took a series of trips back to China to visit his wife and start a family of two children. When Dad came down to Los Angeles before WWII, he hoped to build his business well enough to prepare to bring his family from China and settle into a new life in America. But the Chinese-Japanese War worsened. His parents were subsequently killed by a bomb in China. Then, his wife died tragically. He made plans in November to make his last trip to China to bring his children to America, however, within the following month, his passport approval to make the trip was denied – after Pearl Harbor.

Dad met, courted, and proposed to his second wife, my mother, with a crate of tomatoes in 1944. My mother decided that Dad was a better offer than this World War II soldier from the Bay area who may not return alive. My mother was born in New York Chinatown where Grandpa Ligh managed a dry goods store on Mott and Pell that for decades sustained an extended family of Ligh cousins who worked there until the 1929 Great Depression. By then, Grandpa Ligh decided to take his wife and family of ten kids and return to Guangdong. It was not until twelve years later that Mom and two of her sisters were able to return to the U.S. in 1941 – just before the Pearl Harbor bombing. My two half siblings are about a decade older than my two older sisters, who are nearly a decade older than me and Ray.

We were working class suburban. Paying that mortgage must have been a stretch but Dad made it happen. Dad was always fixing something, and I would be his journeyman. “Marji, you stand here and give me the tool I ask for…” He laid concrete, he did it all. He was a Popular Mechanics magazine aficionado. If they had YouTube then, what could my father have done? In 1961, Dad retired early, and it gave my mother a chance for a new experience. She got her first job outside the home in a garment factory.

In the 1960s, Montebello was very diverse. In my high school drill team, there were Armenians, Mexican Americans, Japanese Americans, working-class Whites, and working-class Jews. In 1965, they built the Armenian Genocide Martyrs’ Monument at Bicknell Park in Montebello adjacent to the golf course.

I graduated from Montebello High School and went to UCLA in the 1970s. Of course, I declared economics as my major, but eventually finished with a degree in sociology with a minor in East Asian studies. UCLA was very exciting at that time. I took Chinese history with Professor David Farquhar, chair of the East Asian Studies program, who recommended I take some “new” experimental courses in Asian American studies. I took Asian Women’s Studies with May Chen, and my teaching assistant was Vivian Matsushige. I volunteered at the Asian Women’s Center and Resthaven in Los Angeles. I tutored with the Asian American Tutorial Project at Castelar on Saturday mornings. I was a student in the early days of Asian American studies! There was all this discussion of “Yellow Power” so, of course, we knew about the Black Power Movement. Oh, the reading lists were hard! We were assigned Stokely Carmichael, Langston Hughes, Malcolm X, Marx, Mao Zedong’s On Contradiction. The expectations were high.

But I also didn’t fit in. I couldn’t afford to buy fatigues (laughs). I didn’t even own a pair of jeans; Mom made my polyester clothes. We were suburban working class. I commuted to campus the first three years. But then I got lucky and won the lottery to live in the dorms during my last two years. To pay for the extra expenses, I was working 25 hours a week as a legal secretary in Century City, traveling there by bus. I had to give up my Ford Maverick. Once in a while, the family would come pick me up to go home to Montebello.

After graduation from UCLA, I worked as an administrative assistant in the Education Department at Occidental College, I was certified as a credentialed analyst; I had to go to Sacramento for that test. And to do that job, I also had to be a notary public.

Asian American Studies M.A. Program

My girlfriend said to me, “Marji, they started an M.A. in Asian American studies program, and you really need to do this. This is what you would want to do.” I entered the program in 1979. I was a teaching assistant for Dr. June Mei. She was brilliant and ominous, but quirky. She spoke so many languages impeccably. I had a hard time with my thesis topic. My first two attempts tanked; experts told me they were not viable. When I got into my third topic on second generation Chinese identity, Lucie Cheng was the one to suggest that I check out the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California in Chinatown.

Lucie Cheng was collaborating with the Chinese Historical Society on this oral history collection project. She gave the project its academic grounding. And then she got us together at UCLA to write Linking Our Lives. I didn’t realize until much later that Linking Our Lives would be the foremost ethnographic study on Asian American women and became assigned readings in women’s studies courses all over the country. We went into several reprints!

The team members were assigned chapters. I was assigned the chapter on “Building Community”. And, I didn’t have a partner. As the deadline neared, Lucie asked me, “Why haven’t you written anything?” I said, “When I listened to the oral history tapes, the women didn’t talk about themselves. They talked about their fathers, their brothers, and their husbands. So, what am I going to do?” Lucie said, “I guess you have to go back and interview them again.” Do you say “no” to Lucie?

I had a hard task. There were no other primary sources! I re-interviewed Marge Ong, Lily Chan, Martha Chow, and others. This was my first time doing oral histories. Remember, this was before digital tape recorders, iPhones, and computers. I was really working hard. I hand wrote notes and jammed it all out before the deadline. I realized these women had done so much for their husbands, brothers, and fathers. And not all Chinese American women were prostitutes or laundry workers. There was so much more that needed to be explored. Now we know Chinese American women did much to build the community in the 1920s, 1930s, and in the home front before and during World War II.

My graduation date was delayed to 1984. At the same time as the Linking Our Lives project, I was deep in Paul Louie’s garage. To find primary source data on second and third generation Chinese Americans, I discovered his collection of old newspapers like Chinese Press, East Wind, and Chinese Digest. I had previously spent some time in San Francisco trying to work with Him Mark Lai. But those scholars were focused on first generation and transnationalism. After I finished my thesis, all these younger scholars wanted to use my bibliography. Asian American studies wanted to better understand the American-born Chinese.

I also had to work to pay my bills. Fortunately, I was on the Health Care Alternatives for Asian American Women research team, working off of a NIMH grant with Dr. Karen Ito. Karen was an awesome role model; she had a collective approach to project management and team leadership. Then I started working at the Asian American Studies Center’s Reading Room as an assistant.

Lucie was a role model for all of us, but she had a tough side. During the 40th anniversary of the ethnic studies centers, Claudia Mitchell-Kernan gave me some perspective. Dr. Mitchell-Kernan was the director of the UCLA African American studies program and then went on to become Vice Chancellor of Graduate Studies. Claudia said, “Lucie and I were the first two academic faculty administrators and it was no small feat.” Lucie came to UCLA in 1970, in the beginning of the women’s movement, and became the Center’s first termed director. UCLA didn’t even have a women’s studies department until 1975. These pioneers had to be tough. Later, Lucie dealt with scholars from the Overseas Chinese Project and founded the Center for Pacific Rim Studies – again at the cusp of such ideas. We now appreciate that Lucie had to build our Asian American studies program with bona fide faculty to ground the program at UCLA. Claudia and Lucie strategized, negotiated, and demanded. We didn’t see a lot of what was going on behind the scenes. Vice Chancellor Al Barber was in charge of research and the Institute of American Cultures (IAC) – which oversaw the four ethnic studies centers.

Continuing Oral History Collections

1984 – the former coordinator of the Reading Room, Jenny Chomori, resigned from UCLA to get her teaching credential. I applied and got the job. Linking Our Lives was published, and I graduated from the Asian American studies M.A. program. In 1987, Lucie got me access to the China exchange program to go to Guangzhou to better my Cantonese. I’ve since taken tours of other Chinese Americans to Guangdong.

I went on to get a Master’s in Library and Information Studies in 1990 and have continued to work at UCLA. In 1994, we were approaching the fiftieth anniversary of the end of World War II. CHSSC members and WWII veterans Jim Fong, Johnny Yee, and Irvin Lai cornered me. They wanted me to help coordinate our CHSSC dinner to honor the Chinese American World War II veterans. Irvin Lai led the vets into Empress Pavilion for a grand entrance. I did my first roll call.

After the dinner, they cornered me again. The three said, “This is not finished, Marji. There are many other veterans and many more stories.” I don’t know why they chose me. I had no interest in military history at that time! It was hard because there was a whole new set of lingo. I didn’t even know the branches of the military much less the officer ranking system. I said, “Why me?” They said, “Because we know you’ll get it done!”

We started to collect oral histories. I had a flashback to collecting oral histories from women for Linking Our Lives. People needed to share their experiences, but they wouldn’t even come forward. The Duty & Honor Project first took shape on the second floor of Phoenix Bakery and eventually found stability at the CHSSC office on Bernard Street. After a few failed attempts to get the veterans out to tell their stories, I bought a huge crock pot and figured out how to make jook in it. I got the condiments to accompany the jook. Then every Saturday, I would sit there – with my rice porridge. Soon veterans would drop by, then come again with their military records. Some weekends were like reunions of memories and friendships.

CHSSC leader Ella Quan became an important supporter. She would bring food to visit me at the Phoenix Bakery office, and then to CHSSC. And then she would say, “It’s time for you to go home. If you don’t go home, then I won’t go home.”

Duty and Honor was published in 1998. Of course, I also helped the Chinese American Citizens Alliance’s Los Angeles Chinese American WWII Veterans Congressional Gold Medal Recognition Project, culminating in our ceremony which I emceed on the U.S.S. Iowa in April 2022. Recently, we got the Library of Congress’ Veterans History Project to recognize the dearth of Asian American stories. I’ve been helping collect more veterans’ stories from Japanese Americans and others. It is interesting that the Vietnam vets are reluctant to come forward. They say, “The country never even acknowledged us since the day we returned. Why do you want to hear our stories now?” It was a sobering, sad, and startling shift from the honorable, proud WWII veterans.

Recently, my cousin turned 80. I’m helping the family sort out her affairs. She was involved in the Los Angeles Chinese American Women’s Club Juniors. I did get a hold of their first cookbook, published in 1971. It has the names of the participants, many of whom have passed on. I’m sorry that much of this history went with them. I got their cookbook’s first edition, first printing from my own sister, Evelyn. Her husband is a 4.5 generation Chinese American. It was probably her mother-in-law that sold Evelyn the cookbook. Evelyn gifted this cookbook to our other sister, and she wrote a poignant inscription in it about being Chinese American and a woman. Evelyn does not usually write things like this! But she wrote it in the cookbook. Our work is not done.