by Dr. William Gow

Editor’s note: Dr. William Gow is a fourth generation Chinese American and Assistant Professor in the Ethnic Studies Department at Sacramento State University. He founded CHSSC’s 2007 Chinatown Remembered Project and is co-director of CHSSC’s Five Chinatowns Project. Gow has been on the Editorial Board of Gum Saan Journal for many years and serves as guest editor for this issue.

Margie Lew arrived at the first meeting of the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California (CHSSC or the Society) excited for the occasion but unsure of what to expect. She had been recruited by her longtime friend Stan Lau, who along with Rev. Paul Louie, had organized the meeting in the conference room of Cathay Bank in the heart of Los Angeles Chinatown.[1] Twenty-seven people attended this pivotal meeting on Wednesday, December 3rd, 1975.

Margie exemplified the type of person who joined the all-volunteer Society in those early years. She was a 54-year-old city employee with two children in college. Despite growing up in San Francisco Chinatown, she had learned next to nothing about Chinese American history. Remembering her time as a youth in San Francisco, she said, “You never read a thing in the history books about Chinese Americans. Not one thing.” When Stan Lau told her about the new historical society, she was excited, “‘It’s about time’, I said. I didn’t know anything about the Chinese except the railroads, the coolies, and the gold mines.”[2]

The founding of the CHSSC in 1975 was part of a movement by Chinese Americans to document their own histories and to push back against the largely Eurocentric curriculum they had encountered from grade school to college. We were all riding the coattails of the African American movement. In 1963, Thomas Chinn and H.K. Wong founded the Chinese Historical Society of America (CHSA) in San Francisco. With help from Him Mark Lai and Philip Choy, the CHSA went on to become the first historical society in the U.S. devoted to the Chinese American experience. In 1965, the Wing Luke Museum opened in Seattle as the first pan-Asian American museum in the United States.[3] There was a common desire to celebrate the history of the people of color in the United States. When coupled with the strikes by the Third World Liberation Front at San Francisco State and UC Berkeley for ethnic studies between 1968 and 1969, this period represented a foundational era. In 1969, UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center (AASC or the Center) was established as a result of much student and community advocacy in Southern California.

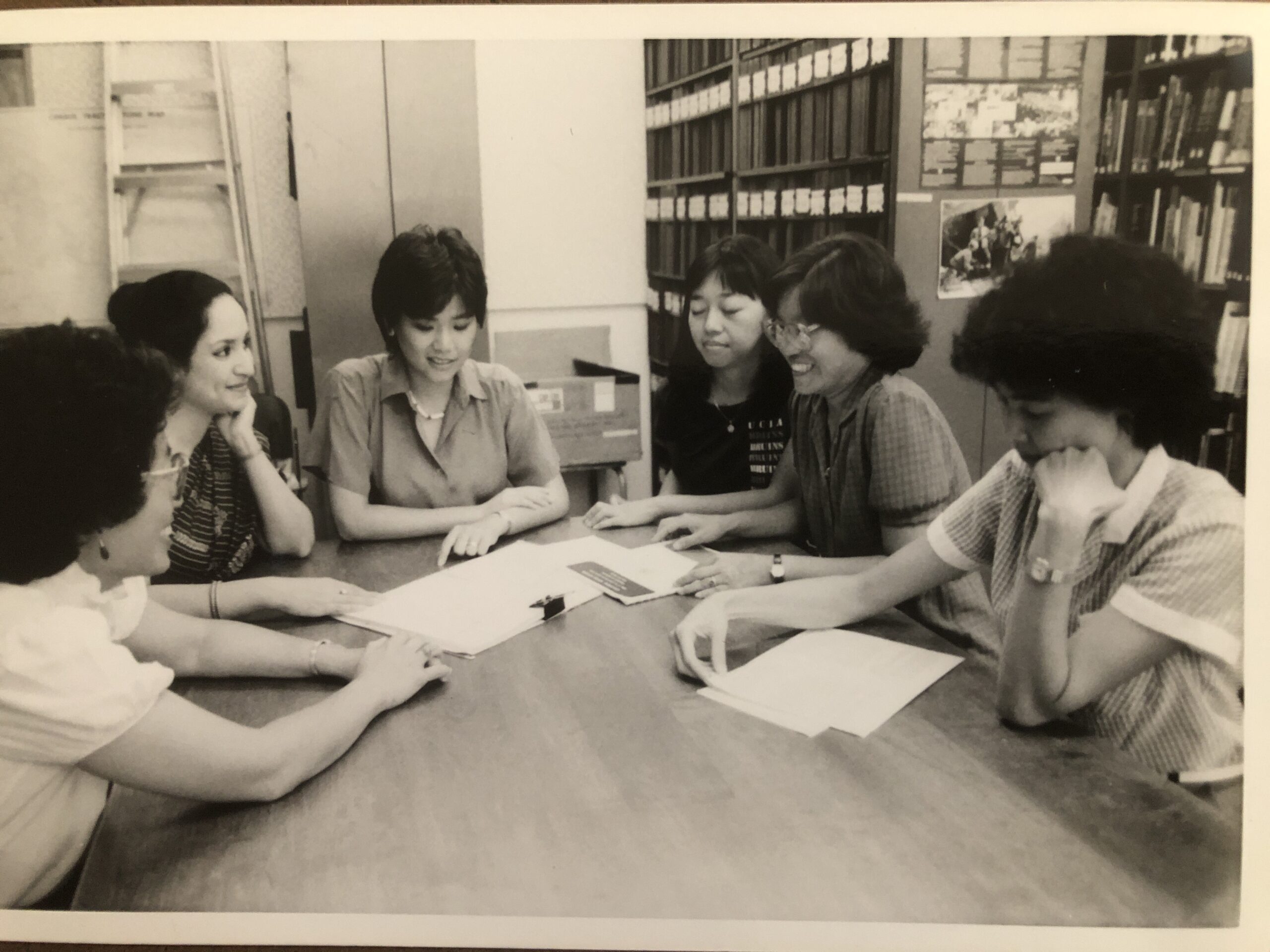

While the CHSSC shared commonalities with organizations such as the CHSA and the Wing Luke Museum, this small but growing historical society in Southern California would distinguish itself with a project they launched three short years after their founding. Working with UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center, the CHSSC founded the Southern California Chinese American Oral History Project. The project represented the community-grounded ethos of the emergent Asian American studies. At the CHSSC, a group of volunteers composed of engineers, teachers, homemakers, city employees and others, would set out to document the everyday stories of Chinese Americans who lived in Los Angeles before the Second World War. Their oral history project would break new historical ground.

The Southern California Chinese American Oral History Project

Oral history was at the heart of the CHSSC’s mission from the beginning. In brainstorming what the goals of a local Chinese American historical society should be, Paul Louie suggested in 1975 a series of “long-range continuing activities” that included “oral interviews” alongside photo and artifact collections, the study of Chinese names, and a “periodic bulletin.”[4] At the second official meeting of the group in January of 1976, Dr. Arthur Hansen of Cal State Fullerton gave a talk on “Techniques in Use of Oral History.”[5] The CHSSC followed this in February by forming an Oral History Committee with Ella Quan acting as the committee’s chair. Stan Lau led this committee in 1977.[6] In July of 1977, the CHSSC hosted an Oral History Workshop at the Chinatown Service Center where workshop attendees used “a seven-question practice interview with cassette tape equipment” to interview each other.[7] That same summer, Stan Lau and the CHSSC were featured in an article in the Los Angeles Times focused on local oral history projects.[8] In the fall of 1977, the CHSSC purchased “modern recording equipment” to record interviews with actors Keye Luke, Victor Sen Yung and Benson Fong at their semi-annual dinner at the Golden Palace Restaurant in Chinatown.[9]

Dr. Lucie Cheng became a professor at UCLA’s Sociology Department in 1970.[10] Professor Cheng was appointed as the Center’s first permanent director, after interim directorships under Alan Nishio, Dr. Philip Huang, Dr. Harry Kitano, and Dr. Alexander Saxton. It was Saxton who hired Russell Leong to edit Amerasia Journal, the academic journal for the field of Asian American studies.[11] Leong oversaw the Center’s publications unit responsible for Linking Our Lives. Near the same time, Dr. June Mei arrived on campus, fresh from completing her doctorate in Chinese history at Harvard. At UCLA, she taught Asian American studies and Chinese history courses. On October 10, 1976, she joined the Society as its 71st charter member.[12] Despite working in the Westside and not driving, Dr. Mei did her best to make it to Chinatown when she could. The CHSSC would eventually make her a lifetime member in part to thank her for her support of the Society. Yet another notable agent and one of Lucie Cheng’s most capable researchers was Suellen Cheng (no relation), CHSSC’s 42nd charter member.

With the CHSSC and AASC advancing on parallel tracks, collaboration made sense. In June of 1978, Dr. Mei invited the CHSSC to participate in the Asian American Studies Center’s “Chinese American Oral History Project.”[13] The AASC wanted support from the CHSSC in three areas: purchasing equipment, assisting with contacts, and providing volunteers to conduct oral histories. The CHSSC spent part of their August meeting “in a lengthy discussion” of the project.[14] By the end of the month, the Board had made a decision. The Board sent a letter to Dr. Cheng informing her that the Society “wholeheartedly endorses the project” and pledging both material and volunteer support for the project’s duration.[15] Following the Asian American Studies Center’s September announcement of the project, Dr. June Mei was appointed project director.[16] Dr. Mei then hired Jean Wong as the project’s sole paid interviewer.[17]

Jean Wong was joined by CHSSC volunteers including Emma Louie, Suellen Cheng, Munson Kwok, Stan Lau, Dora Lau, George Yee and others. In October of 1979, Beverly Chan replaced Jean Wong as the project’s paid interviewer.[18] Beverly Chan was a UCLA graduate who was born in China and who had immigrated to the U.S. as a youth. By 1979, she had lived in Los Angeles for thirteen years and worked as an English as a Second Language (ESL) teacher. She would continue in that capacity until the project completed interviews in 1983. Bernice Sam, a retired L.A. high school teacher, joined the project as a second paid interviewer.[19]

In October of 1979, Dr. Lucie Cheng and Dr. June Mei left for Taishan in Southern China. The Asian American Studies Center announced that the two would spend “several months researching the Chinese emigration to America and the return of the sojourners.” Part of their time would be spent conducting oral histories with “sojourners and their descendants” as “a complement to the project here in L.A.”[20] With June and Lucie both in China, Suellen Cheng became the acting project director in October of 1979.

In many ways, Suellen Cheng was the heart of the oral history project. Cheng was active both in the Society and at UCLA. Suellen had been a part of the Society from the beginning, attending early meetings at Cathay Bank. She completed her master’s degree in U.S. history in 1976 at UCLA, and then continued into the Ph.D. program. As the acting director of the project, she was also a paid employee of the Asian American Studies Center. She was instrumental in drawing up the list of people to be interviewed. She pushed for more interviews with working class Chinese Americans and women. Suellen conducted dozens of local interviews for the project.

Suellen Cheng was also instrumental in summarizing and indexing the interviews. As Bernice Sam, Beverly Chan, and the others collected oral histories, a separate group composed mostly of CHSSC volunteers set out to create finding aids and summary transcripts: Margie Lew, Elaine Lou, Don Loo, Eugene Moy, and Elmo Gambarana. Cheng met with these volunteers every Saturday and used old cassette recorders to complete the summary transcriptions. When the task proved too Herculean, Lucie Cheng applied for and was awarded a National Endowment for the Humanities grant in 1982 to complete the summarizing and indexing of the interviews. The project hired a college student, Stella Ling, whose sister Susie Ling would become one of the authors of Linking Our Lives. Debra Hansen was hired as indexer. With the advent of the grant funding, the Center promoted Suellen Cheng to a position as paid Project Coordinator.[21]

In the coming years, Suellen would also be the bridge between the Chinese American Oral History Project and the book Linking Our Lives. Other than Lucie, Suellen Cheng was the only author of the book who also worked on the oral history project.

The Book: Linking Our Lives

Dr. Lucie Cheng was the one who sparked the idea for Linking Our Lives. In 1978, Dr. Cheng had begun to focus part of her research on Chinese American women.[22] In 1979, she published an essay examining Chinese American prostitution in the 19th century.[23] Dr. Cheng was part of a group of scholars at UCLA who were pushing for the inclusion of women’s voices in American history. Among these scholars was Dr. Kathryn Kish Sklar, a U.S. history professor who was also an advisor to Suellen Cheng on her research as a graduate student.

By the beginning of 1983, the Society and the Center began discussion of writing a book based in part on the oral histories collected over the prior five years. In March of 1983, Dr. Cheng wrote to the Society proposing that the Center could convene a group of researchers “to prepare a manuscript of about 60-100 pages on the subject of Chinese American women in Southern California.”[24] Dr. Cheng proposed completing the project by September of that year. The Society would be responsible for providing photographs. The Center and CHSSC would then create a joint committee to finalize the draft of the book with a goal of completing the entire project by the end of the 1983 calendar year.

Once this agreement was set, Dr. Cheng began recruitment of her writing team. The UCLA authors included Suellen Cheng; Dr. Judy Chu, then a recent doctorate in psychology who was a lecturer in Asian American studies; Sucheta Mazumdar, a graduate student in Chinese history; two graduate students from the M.A. program in Asian American studies, Susie Ling and Marji Lee; Dr. Feelie Lee, a student advisor on the campus; and Elaine Lou, an undergraduate student. In her role as director of the Asian American Studies Center, Dr. Cheng had been instrumental in starting the first graduate program in Asian American studies. Dr. Judy Chu would be elected to the U.S. House of Representative in 2009.

Dr. Cheng and her writers had periodic meetings on the campus. What these scholars shared was a passion for community history and desire to give voice to Chinese American women who had long been left out of the historical record. When it came time to choose a title for the book, they circled through many ideas including “Crossing the Bridge,” “Seeking Identity,” and “Looking Back, Moving Forward,” but the title the group eventually decided on spoke to the project’s goal of linking the lives of the project participants together with one another and then collectively with those who had come before them.[25]

These women joined a growing circle of writers and community historians across the country pushing for the inclusion of Asian American women’s voices in the national historical narrative. Monica Sone’s Nisei Daughter was published as early as 1953, and Betty Lee Sung’s Mountain of Gold: Chinese in America in 1967. Berkeley students and Stanford students published collections entitled Asian Women (1971) and Asian American Women (1976). Gidra, the Asian American movement newspaper from 1969 to 1974, had several articles on Asian American women. Maxine Hong Kingston published her memoir Woman Warrior in 1976. In 1978 and 1979, Judy Yung, then a librarian at the Asian branch of the Oakland public library, published two articles on Asian American women in the publication Bridge. Yung would go on to work with Genny Lim to produce an exhibit entitled, “Chinese Women of America, 1834-1982,” that traveled the country, including a stop in Los Angeles sponsored by the CHSSC. Lim and Yung then turned their exhibit into a book published in 1986. In 1980, the National Institute of Education published papers from the Conference on the Educational and Occupational Needs of Asian Pacific American Women, originally held in 1976. Ruthanne Lum McCunn’s published her historical novel, Thousand Pieces of Gold about the nineteenth century Chinese immigrant Polly Bemis in 1981. Dr. Nobuya Tsuchida edited Asian and Pacific American Experiences: Women’s Perspectives in 1982. Berkeley’s Elaine Kim authored Silk Wings: Asian American Women at Work in 1983. What separated Linking Our Lives from all these earlier works was that this book told a collective story specifically of Chinese American women – rather than a larger story of Asian American women or a single story of a specific woman or family.[26]

As we look back at both Linking Our Lives and the Southern California Chinese American Oral History Project, now is an opportune time to reevaluate the significance of these two projects. These projects would form the basis for much of the subsequent historical work undertaken by the CHSSC, from books like Bridging the Centuries and Sweet Bamboo, to oral history projects like Chinatown Remembered and our current Five Chinatowns Project. Forty years on, we can see that these two projects are historical events in their own right that warrant documentation. With this in mind, this issue of Gum Saan Journal explores the circumstances that caused the women and men to be involved in creating these two projects.

[1] The idea for a society originated at a lunch conversation between three men: Reverend Paul Louie, Paul M. De Fella, and Bill Mason, who worked for the Los Angeles County Museum. The groundwork for the first meeting was laid by Paul Louie and Stan Lau who chaired an ad hoc committee formed to launch the group.

[2] Margie Lew. Interview with William Gow on November 23, 2021.

[3] Sucheng Chan, “Chinese American Historiography: What a Difference Has the Asian American Movement Made?” in Chinese Americans and the Politics of Race and Culture, Sucheng Chan and Madeline Hsu, editors (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2008), 22-23.

[4] Memo from Paul Louie to Gerry Shue of June 24, 1975, CHSSC 1975 Business 1976-1989, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California Records.

[5] Meeting Notice of January 7, 1976, 1975-1980s Business 1976-1989, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California Records. Dr. Arthur A. Hansen is now professor emeritus of History and Asian American Studies at Cal State Fullerton. In 1972, he was the founding director of the Japanese American Project of the Oral History Program.

[6] Meeting Minutes of February 4, 1976; Meeting Minutes of February 2, 1977, 1975-1979 Binders, Volume 1, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California Records.

[7] Meeting Minutes of September 7, 1977, 1975-1979 Binders, Volume 1, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California Records.

[8] Mark Jones, “Search for Roots by Oral History”, Los Angeles Times, July 4, 1977.

[9] “Modern Equipment to Record Old History,” CHSSC Press Release, October 24, 1977.

[10] In some sources from the period, Lucie Cheng is referred to by her then married name, Lucie Cheng Hirata.

[11] Letisia Marquez, “Obituary: Lucie Cheng, 70, Former Director of Asian American Studies and Founding Director of Pacific Rim Studies,” UCLA Newsroom, February 8, 2010.

[12] CHSSC Charter Members as listed by George Yee, 1975-1980s Binders 1975-1979, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California Records.

[13] Meeting Minutes of June 7, 1978, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California Records.

[14] Meeting Minutes of August 9, 1978, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California Records.

[15] Letter to Lucie Cheng Hirata from the CHSSC Board, August 21, 1978, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California Records.

[16] “Center Starts Oral History,” Cross Currents, Newsletter of UCLA Asian American Studies Center, Vol II. No. 2, September-October 1978, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California Records.

[17] Jean Wong was hired in January of 1979. Southern California Chinese American Oral History Project Progress Report, June 14, 1979.

[18] “Voices from the Past,” Vol I. No. I, October 1979 (UCLA Asian American Studies Center), Chinese Historical Society of Southern California Records.

[19] “Voices from the Past,”Vol II. No 1. February 1980 (UCLA Asian American Studies Center), Chinese Historical Society of Southern California Records.

[20] “Voices from the Past,” Vol I. No. I, October 1979, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California Records. While Dr. Mei reports that she deposited these oral histories she conducted in China in the UCLA library system, none of the current library staff could identify their location.

[21] Personal Correspondence from Suellen Cheng to the author, August 17, 2023.

[22] “Research” Cross Currents, Newsletter of UCLA Asian American Studies Center, Vol II. No 1. September-October 1978.

[23] Lucie Cheng Hirata, “Free, Indentured, Enslaved: Chinese Prostitutes in Nineteenth-Century America,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Vol 5, No. 1 (Autumn 1979): 3-29.

[24] Letter to Eugene Moy from Lucie Cheng, March 7, 1983, CHSSC 1975-1980, Misc. Business, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California Records.

[25] Notes, Book Business 1984, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California Records.

[26]There were also collections that focused in part on the experiences of Chinese women as part of the larger Chinese American community. These included: Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island (1991) and Nee and Nee’s Longtime Californ’ (1986). Special thanks to Kelly Fong, Sine Hwang Jensen, Susie Ling, Isa Quintana, and Dorothy Rony for help with this bibliography.