– Richard and Lily Leong Wong

Editor’s note: Both Richard and Lily grew up in Chinatown in the 1950s. Richard’s family ran a gift shop in West Chinatown Plaza, while Lily’s family lived on Grand Avenue and established the Quon Yick Noodle Company nearby. After graduation from college, Richard and Lily both worked at Chinatown Service Center. By the late 1970s, Lily was a teacher at Castelar Elementary where she taught for over thirty years. Dick managed Imperial Dragon Gifts and Golden Dragon Gift Shops in the Central Plaza of Chinatown. Richard’s sister, Dorothy Wong Lee, and Lily’s brother, Henry Leong, were featured separately in Gum Saan Journal 2018.

Dorothy, Richard, and Helen

on Chung King Road.

Photo courtesy of Richard Wong.

Family Roots

Dick —I was born in 1950 here in Los Angeles. If you want to know about my family roots, you’d have to talk to my wife (laughs)…

Lily—This is what Dick’s mother told me… Dick is 4th generation American. His great-grandfather came to work on the railroads. He left Taishan 台山 because of the famine. The Wong 黄 ancestor worked in a laundry in the Midwest. Whatever money he could save, he wrapped it in newspaper and sent it back to China. Eventually, Dick’s grandfather also came. After settling down in Los Angeles, he established a hotel on 7th Street and Central, near the wholesale grocery area in Los Angeles. Grandfather would save up to go back to China several times. Each time, he had a child. The first four of these children were girls, and then the 5th child was Dick’s father, Leonard Wong. After Leonard became a teenager, he came to Los Angeles. Leonard graduated from Poly High.

He was then drafted into the U.S. Army during World War II. Leonard didn’t talk much about the war. He was a very young teenager at that time. But after the War, he returned to China for a war bride, Ginger Hom Wong When Leonard came to America, he had taken on the identity of his fourth sister—who had been given a male-sounding name on purpose. He was actually three or four years younger than his sister. The family participated in the Confession Program in the 1950s. This 4th sister eventually came to Los Angeles too; she’s about 95 years old now and lives in Chinatown.

Dick—My older sister was born in 1948, and our younger sister was born in 1951. Near that time, Dad left his father’s hotel business and, at the advice of our first cousin, he bought a retail storefront near our cousin’s store in Chinatown West on Chung King Road. We lived upstairs from the store. We would return to see Grandfather at the hotel to get ice cream treats.

Lily—I was also born in 1950 in Los Angeles. My dad came to America after being adopted by his uncle in the 1920s. His paper father was an herbalist in San Francisco. While my father-in-law got drafted into the Army as a young teen and fought from the trenches of Europe, my dad enlisted towards the end of World War II when he was almost 40 years old. The Air Force base was in England; he served his brief assignment stationed there. After serving in the war, he became an American citizen. This gave him the right to return to Hoiping (Kaiping) 开平 and marry a wife, Lo Kwon Ying.

My mother was one of the first war brides from China who actually flew to the United States instead of being on a ship in the late 1940s. She said they enjoyed a celebratory stopover in the Philippines and were treated well. Because my father was older, he did not pursue a higher education nor take advantage of the GI Bill. His cousin, William Y.S. Tom, was able to utilize the bill.

He attended college and optometry school after serving in the military. Upon graduating, he opened his practice in the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association building, which is in the heart of Chinatown. Meanwhile, my parents settled in Los Angeles and were part of an herb partnership on Spring Street, Tin Yin Hong. My oldest brother was born in 1949 and my younger brother was born in 1951—stairstep kids.

As communist China was then shutting down, it was getting difficult to import medicinal herbs. It had to come through Mexico. Eventually, the U.S. government prohibited importing herbs from China totally. Dad had to close his shop. For a while, Dad worked at Far East Café as a chef with the Jungs. While my mother was going to English language school, her “war bride” classmates would comment at lunch on how delicious my mom’s fresh noodles were. That gave my parents an idea to make noodles Dad invested in a small dough mixer and a dough presser and started experimenting with noodle dough recipes. In the mid-1950s, my parents decided to go into business making noodles for the Chinese restaurants. In order to meet the financial needs of a growing family and a startup business, Mom took on a second job. She was a downtown seamstress by day and made noodles at our factory by night. When we were younger, Mom would sew all the clothes for me and my brothers. She had developed an interest and skills for sewing.

Growing Up in Chinatown

Photo courtesy of Richard Wong.

Dick—There was a group of us kids in Chinatown West. We lived a sheltered life as our geographical boundaries were very limited. Castelar School was a block away. Nightingale Junior High on Figueroa was a little further. It wasn’t until Belmont High School and college, when we started driving, that we came to know areas out of Chinatown. My world was centered around Chinatown: work, home, school, friends, and even church. Our parents were working in the retail business with long hours every day. When my parents needed help, they would call us from upstairs. Of course, my older sister was the most responsive and did much of the work.

Lily—Their son was spoiled (laughs).

Dick—There were about ten families in West Chinatown with about two or three kids each. This included my cousins. I don’t know exactly how we are related, but we are very close. On our visit back to Taishan in the 1970s, I saw that my father and Uncle Leland were from the same village. Our parents were also members of the Wong Association. Dad was the president of the Wong Association at one point, but I was never involved.

We kids played and played. Of course, we fought too (laughs). At that time, the biggest thing on TV was roller derby. So we set up our own derby around the Chinatown West wishing well, just west of Hill Street. We would elbow each other, trying to knock each other down as we skated. One time, my sister Dorothy was pushed and skated straight toward Hill Street. We all yelled, “Fall, fall, fall.” So, yes, it was a bit dangerous (laughs). I was between five years of age to nine years old. We played with girls when we needed them to make a team (laughs).

We did all the other sports. On both ends of West Chinatown are parking lots—one for the French Hospital, and on the other end was the Ling’s Market’s parking lot. The Ling family was also a part of our group; so that’s where we played our serious sports: baseball, football… We never played Chinese games.

Lily—Some of the West Chinatown kids were part of a lion dance troupe. The boys and girls were trained to take part in the annual Chinese New Year’s celebration and parade around Chinatown. Classmate Young Lee’s dad was the sifu.14 On summer days, Dick’s dad would take the kids to the community pool at Highland Park. When the business was slow, other dads would join in to play softball with them at the Ling’s parking lot.

Dick—Dad liked to play all kinds of sport. Sometimes, the kids in the neighborhood and church friends came to our basement to hang out, read comic books, and play ping pong. My dad played ping pong, too. When Dorothy was a little girl, she really enjoyed watching Leo Politi sketching around Chinatown.15 Dorothy became an artist as well as an art teacher, initially at Belmont and later at Marshall High School.

Lily—Although we were living near Chinatown, my brothers and I never went out to play with any neighboring kids. The noodle factory was located at the busy intersection of Sunset and Figueroa; therefore we spent most of our day in the factory, from morning to night—even up to midnight. My parents rarely took a day off during the beginning years of starting their business. However, each year during the Chinese New Year celebration, my Dad carved out time for the whole family to visit Grandpa and Dad’s friends in San Francisco for two weeks. Grandpa was the only relative my parents had in California. Eventually, many relatives and friends were sponsored, supported, and finally immigrated to America. Upon arrival, many lived at our home and worked at our factory until they felt established enough to move out on their own.

When we were little kids, all three of us would help at the factory by doing some light tasks: folding noodle boxes, packing, weighing the noodles as well as tying the boxed noodles. As we grew older, my brothers would take on heavier jobs, like taking out the dough from the mixers and prepping it in the rolling machine before feeding the dough through the noodle cutter. Being the girl in the family, my duties were lighter: answering the phone, serving the walk-in customers, weighing and packing the wonton skins.

We were in junior high when my parents added fortune cookies to the list of products manufactured at the factory. My brothers and I rotated this job of making fortune cookies on weekends and during our summer breaks. Besides getting paid for our work, my parents rewarded my brothers and I beyond most kids’ expectations at the end of each summer. They took us to all the amusement parks in Southern California: Disneyland, Knott Berry Farm, P.O.P.—Pacific Ocean Park, Sea World, and Magic Mountain just before the school year started.

We weren’t given the opportunity to go swimming or go biking like Dick. In fact, I still fear water, and I still can’t ride a bike (laughs). I did play with dolls, and we had a swing in our backyard. When we had down time at the factory, my brothers and I would read our Marvel comic books, play Chinese chess or checkers, cards, or mahjong. Sometimes our Dad would join us with the table games. One other activity we enjoyed in the summer was listening to Dodger baseball, play by play. We had a TV at home, but my brothers and I couldn’t control ourselves once we turned it on for the Saturday cartoons.

My brothers and I all pitched-in to cook and clean at the factory also. Dad had installed a kitchen at the back of the store with a large wok. We ate rice for dinner even though we were in the noodle business. Our dad was “old school” in that he still felt that rice was the staple. However, for lunch, he was quite lax. In fact, he encouraged us to eat whatever was available or simple enough for us to prepare ourselves. This repertoire included cha siu baos, siu mai, hot dogs, hamburgers, tuna or Spam sandwiches, spaghetti, and even tacos.

Dick—Dad spoke English. My mom’s English was more broken. We kids spoke English to each other. We only spoke Chinese to the parents. I was not aware that our parents spoke different dialects. We were ABCs all the way. When I was sent to Chung Wah Chinese School for a few years, all I can remember was playing Warball there.16 I didn’t even get that Chung Wah was teaching us Cantonese while I spoke the Taishan dialect. No wonder I had a hard time learning!

Lily—We spoke the Hoiping dialect in my family. It sounds much closer to Cantonese in its phonetic accents and tones. We had it easier. I also spoke English with my brothers.

Dick—During the 1950s, China was under communist rule, and the Chinese Americans were not thinking about going back to China or anything like that. Not at all. We did return—with our parents—for visits in the 1970s.

We went to First Chinese Baptist Church at the end of our block. The Church started in the 1950s at a vacant noodle company at the corner of Chung King Road and Ling’s parking lot, a few storefronts from our store. We are still active members of Chinese Baptist.

Lily—We attended the Chinese Assembly of God, which was formerly in the Echo Park area. It was started by an American missionary who had to leave Malaysia in the 1950s. Interestingly, Esther Sandal spoke perfect Cantonese. Today, Chinese Assembly is located closer to Chinatown in the Lincoln Heights area on Avenue 22. At 95 years old, my mother still goes weekly.

Our leisure activity as a family was to see Chinese movies, about twice a week. There were the Kim Sing, Sing Lee, King Hing theaters, and for a short while, another one on Broadway.17 My brothers and I especially enjoyed watching kung fu movies from Hong Kong. We also got exposed to Mandarin language through the movies.

Dick—My parents also liked the Chinese movies. When we moved to the “suburbs”—a few blocks away to New Depot Street, we walked to the Kim Sing theater. And we did that two or three times a week. Even when I was in college, I would return to join my parents to watch those kung fu and tear-jerking Chinese soap opera movies. Just recently, I found a TV channel that shows reruns of these kung fu movies, and I am enjoying them again. Chinatown may still be in me (laughs).

At Castelar, there were Hispanics and non-Chinese. But I thought of them all as a part of the life in Chinatown. We had no barriers between us; we knew no color. In junior high, our class was very mixed and very close. We would challenge the higher class to tackle football games. My White friend, Ronald Gannon, and I would go get our Hispanic friend, Manuel Morales, and head to the “Dogtown” projects to pick up Marvin Strokes, our Black running back to form our team.18 It was all very natural. We didn’t know we were different colors. We would go to each other’s houses before heading to the football games together. Manuel came over to my place a lot. In high school, we went in different directions.

My parents had hopes for me, but I didn’t really feel pressure academically. My main interest was in sports. I’d play anything that’s available: basketball, tennis… My dad was a serious football fan, and he wanted me to go to USC. I broke his heart when I went to the “other” school, UCLA!

I graduated from high school in 1968. I didn’t know anything about McCarthyism or communism. Of course, we had heard about the civil rights movements of the 1960s, but it was not part of our world. My world started as one block of Chinatown. And in this world, we were always racially mixed. By the time I got to high school, I discovered a little more. I met Japanese Americans and Filipino Americans. When I got to UCLA, I was shocked as it was over 80% White!

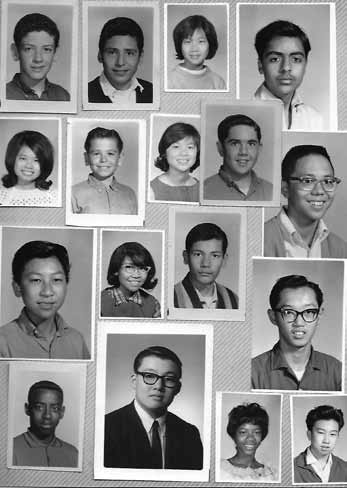

Nightingale and Belmont schools.

Photo courtesy of Richard Wong

Lily—In the 1950s, we weren’t aware of the political climate. We just knew that our relatives in China were experiencing a lot of problems. They wrote frequently asking my parents for financial assistance. They were not aware of the fact that my parents were working hard long hours to make a living and to start up a business. Mom told me that to help meet the greater financial needs of my dad’s family and her own family in China and Hong Kong, she took on the second job at that time as a seamstress. It provided a steady income at 75 cents an hour; it also meant that a $10 monthly commitment to the needy families was possible. Eventually, both grandmas and uncles were able to escape China, relocate to Hong Kong, before immigrating to the U.S.

We worried about the safety of friends during the Watts Riots. Our family friends, the Tueys, had lived near Chinatown on Alpine before moving to 42nd Street, behind USC. Mrs. Tuey and my mom were best friends from the time they first met as fellow war brides in their English class, till now. Because of the unrest at that time near their home, my mother kind of adopted one of her friend’s four daughters. She was to attend Manual Arts High in the fall, but our family sponsored her transfer to Belmont High School. She became my classmate.

Dick—I knew Lily since Castelar days. But I never said a word to her. I finally asked her out for a Grad Day celebration after high school graduation. We went to Disneyland and Knotts Berry Farm with some classmates and friends.

Lily—We were classmates in 6th grade, junior high, and high school. Dick, however, was placed in the AE or Academic Enrichment classes in high school, while I was placed with the regular students.

The Sixties and Seventies

Dick—The Vietnam draft was held on a lottery system based on birthdays. I was in group 14 out of 365. I was drafted in my second year of college. I went through the swearing-in ceremony and everything. But at the very end, I didn’t qualify, as I had serious sports injuries. I couldn’t really run. My parents and I were very relieved.

My father wanted me to go to USC, but it was very expensive and not very financially realistic for our family. My older sister Dorothy was already in college, and my younger sister Helen was due to graduate from high school the next year following me. In my circle of 30 high school classmates, about 22 went to UCLA. Perhaps there was a lot of herd mentality going on (laughs). Even my close friends from church went to UCLA.

Like most Chinese parents, they thought becoming an engineer would be the most financially stable and rewarding field, but I graduated as a business/economics major. UCLA was not Chinatown. UCLA was over 80% White, and it was a different world. You could see differences in race, culture, class, and educational preparation.

I didn’t know of any direct discrimination, but there’s always discrimination. If you are the second one chosen, is it because of your color? While in college, we did form a fellowship club comprising of students from our church.

In those days at UCLA, you couldn’t avoid all the demonstrations and strikes for ethnic studies, anti-Vietnam War, etc. There was this one quarter, that aside from the midterm and final, we never met for class. I didn’t march as I wasn’t very political. But you couldn’t avoid being part of it all.

Lily—Ever since I was twelve years old, I knew I wanted to be a teacher. When I became a teenager, I volunteered to teach Sunday School in church. I never wanted to follow Dad into the noodle business (laughs). My mom had said that since I was a girl, I didn’t need to think about attending college as I was going to get married and all. However, while in high school, I knew that my parents were proud of my academic achievements; their stance began to shift.

I had heard that Cal State Los Angeles had a good teachers’ program, so that’s where I went. I had a hard time transitioning to college. Cal State was on a quick quarter system; it didn’t help to be a Winter grad entering college mid-year. Cal State was a commuter campus. This made interaction with friends from Belmont with our diverse majors and schedules extremely difficult. To develop new social relations was equally impossible. I never felt direct discrimination though.

At this time, my father had a definite change of heart concerning my attaining a college education. My parents supported me in my decision to enroll in a smaller campus sponsored by our church denomination, Southern California College in Costa Mesa. SCC was on a semester track, and I got back into my teaching program. Dorm life on campus was an enriching experience. My dorm mates were ethnically diverse and were from around the world: Navajo Indian, Samoan, Mexican, Colombian, Kenyan, Australian, Pakistani, Canadian…

Dick—After graduation in 1972, I went to work for the state at the Employment Development Department (EDD), job counseling for the unemployed. I did that for a few years. Chinatown Service Center was just opening when I went to work there. There was a job development program focused on Vietnamese that were coming in after the war. I left the comfortable state position to help develop this program. We trained the newcomers in basic English, taught them how to fill out application forms, developed their resumes, and we even had to teach them how to ride the bus to go to job interviews or to their newly attained jobs.

I speak Chinglish. We had interpreters working with the Vietnamese, but a lot of times, you just get by.

I was with Chinatown Service Center for six years. The funding for those programs was always uncertain. It didn’t matter if we did a good job or not, the funding was based on political interests. The time came for me to leave Chinatown Service Center and help in the new family business venture in Chinatown’s Central Plaza.

I felt Chinatown was home. Even though Chinatown was not the same as the one I grew up in, it was my calling. Our generation was very Americanized when I was growing up, even though my Toisan mother was very traditional. But still, Chinatown was home. I grew up there, I played there, I went to school and church there.

Lily—During college, I got a part-time job with the preschool at Fountain Valley Baptist Church. After college, I was invited to teach the kindergarten class at the school. I thoroughly enjoyed my teaching experience there. The students were high achievers and highly motivated to learn. A few of my blond and blue-eyed kids would call me “Mom!” Initially, I was shocked. I knew that I didn’t look like their mothers whatsoever. However, as I thought about it, I felt that it was actually a compliment…I was meeting a relational need in those kids.

At that time, there were a lot of Asian American college-aged students going to Taiwan to study Mandarin. I did that too. I may have been influenced by the 1970s Asian American identity movement. My parents made me take my young sister, Lotus, with me to be my companion. She was a 4th grader at the Taipei American School. We stayed in Taiwan for just under a year.

After I returned from Taiwan, our family friend, Joyce Law, the founder and director of Chinatown Service Center, asked me to join her staff in teaching basic English and job search skills to the Vietnamese refugees. That was in 1978.

Photo courtesy of Richard and Lily Wong

Dick—It was at that time I hooked up with Lily again.

Lily—Dr. Bill Chun-Hoon, principal of Castelar Elementary School, upon hearing that I was a credentialed elementary teacher, recruited me to help implement a new bilingual curriculum that focused on teaching the non-English students and limited English students. I felt so blessed to be able to return to Castelar, my alma mater, and use my language skills to help the refugee students learn English. My former school nurse, Mrs. Suto, former 4th grade teacher, Mrs. Reece, and former 2nd grade teacher, Miss Attorick were still on staff when I returned to Castelar. I retired from Castelar 33 years later.

Dick—My mom and dad were still running the West Chinatown shop. With their help, my sisters and I opened a new giant shop in Central Plaza. Central Plaza was where all the action is. That’s where all the parades and activities are. When I was a kid, I always said, “Dad and Mom, when I graduate, I’m getting out of here. I’m never going to work at the shop. No way am I going to work at the shop.” Guess what? I came back to work at the shop (laughs)!

Lily—The widow of attorney Y.C. Hong, Mabel, made a restaurant space that was Fon’s available to us. That’s how we came to establish Imperial Dragon Gifts at 451 Gin Ling Way, Chinatown’s Central Plaza.

Dick—We all would say, “I’m never going into the restaurant business. I’m never going to work in Chinatown.” But we came back around 1979. We would work after school and weekends as we had other jobs.

Lily—It was Dick’s parents’ dream to move over to Central Plaza. It became a family venture for all of us. I would work at the gift shop after teaching at Castelar.

451 Gin Ling Way, circa 1980s.

Photo courtesy of Richard Wong.

Chinatown Today

Dick—Today, Chinatown is different. There’s a lot of gentrification. Is it still “Chinatown”? Central Plaza has the Chinese-style architecture, and it has become a great movie or video set on many occasions. But it is changing—especially on the Chung King Road side. It’s not retail; it’s an art district. The storefronts are all closed except for late Friday night openings. Soon, the old Chinese Americans won’t be able to afford renting or working in Chinatown. I still have a traditional gift shop for tourists, but more and more of my space is being diverted to housewares to supply the residents of the new apartments and condos developed nearby. The clientele for our store is changing.

Lily—In the 1950s, Chinatown offered something to that first generation of Chinese immigrants like my parents who were, at times, homesick for China. It triggered fond memories of their family and customs, including the food and the cultural activities. One interesting habit that my parents developed to combat this homesickness was to check out the Chinatown of each city they were vacationing in. Today, LA’s Chinatown is not the same. Even Chinese restaurants of various regional cuisines are leaving Chinatown.

Dick—The peers that I grew up with have dispersed. They aren’t involved with the life and activities of Chinatown. I have memories. I hate to see Chinatown go, but I can’t stop the changes. I am still part of a merchants’ group. There are older members like the Louies and the Quons who are from the earlier days. I’m from the middle group. But now, there is a new wave coming in.

Our children say what I said, “No way will we work in the shop” (laughs). They are professionals and have their own careers. Sooner or later, they’ll need to decide what to do with our investment in Chinatown. They probably won’t be as hands-on. They may manage a food court or some other new business venture. We’ll see what direction they will take the future of Chinatown.

Lily—Our children didn’t go to Chinese school. They grew up in the Silver Lake community. But our daughter Danielle married Wei Li from Shanghai, and now their children are learning Mandarin to converse with their Shanghainese grandma. Our son Doug married Lisa from Taiwan; their child is learning common phrases too. My Mandarin is getting better now with all these sandwiched opportunities to practice!

_____________________

14 Sifu 师父is a teacher of martial arts.

15 Leo Politi (1908-1996) was a renowned artist that illustrated over twenty children’s books—including Moy Moy (1960) and Mr. Fong’s Toy Shop (1978). He often worked in the areas around Olvera Street, Bunker Hill, Little Tokyo, and Chinatown. He has a mural at Castelar Elementary.

16 Warball is similar to dodgeball. Chung Wah Chinese School—or the Chinese Confucius Temple School—originated in the 1920s in Los Angeles’ Old Chinatown. With the support of the C.C.B.A., it moved to 816 Yale Street in New Chinatown. In the 1980s, over 1000 students were enrolled in learning Cantonese language and some Mandarin.

17 Chinese language movie theaters included Kim Sing Theater at 722 N. Figueroa, Sing Lee on Spring Street, and King Hing Theater at 649 N. Spring Street.

18 “Dogtown” was slang for the William Mead Homes on the northeast corner of Chinatown off of Main Street. These projects were built by the 1937 Housing Act. It gained the moniker as it was near the Los Angeles’ historic Ann Street Animal Shelter, open from 1928 to 1988.