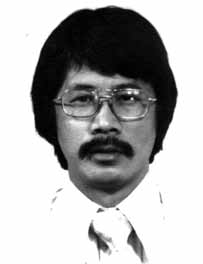

– Wong Chur Fon 黄紹寬

Editor’s note: This essay, authored in 2020, tells another story of the 1950s. Born in 1938, Wong Chur Fon was one of the last paper sons who came to Arizona in 1951. By day, he appeared as the typical high school boy. But after school, he was working off a huge debt. Indeed, Wong Chur Fon has “a story to tell.”

Photo courtesy of the Wong Family.

A Story to Tell

My name is Wong Chur Fon 黄紹寬. I was born in 1938 and became a 2nd generation paper son with the name of Dong Moon Chong 邓文章. I’d like to tell my story of being a paper son from the first person’s perspective.

It all started with my paper grandfather, Dong Ting Yen, who established his US citizenship after the 1906 San Francisco Fire. He recorded 9 sons and 2 daughters living in China. Actually, he had 7 sons and 2 daughters, creating 2 paper son slots. My paper father was, in actuality, his nephew.

My paper father, Dong Cho Sound, was born in 1906 and married to my mother’s elder sister. They had 1 son and 2 daughters. He immigrated to America from Kaiping 开平 in 1919. On his returns from America, he recorded 3 sons, creating 2 paper son slots. I used one of these slots to emigrate from Hong Kong in 1951.

At the age of 10, I was chosen to come to America. It was a decision made by my parents, my aunt, and her husband. For the next 3 years, my main focus was to prepare and learn enough knowledge to pass the immigration interrogations. There was no room for failure. I had to acquire as much details as possible about my supposed family. I would go live with my aunt, my paper mother, whenever possible, to acquire the local speech patterns. The differences between Taishan 台山, my home district, and Kaiping, the district of the paper family, were minor, but there were differences. I would memorize the details of the “coaching book” about my 8 other uncles, their spouses, and children. I memorized their names, birth dates to the hour and minute, dates of marriage, dates and name of the ships for their trips between China and America.

In 1948, at the age of 10, it was an exciting time for me to ride in an automobile for the first time. My 1st paper brother had come back from America after high school to get married. It was then that we submitted immigration applications not only for me, but for 2nd paper brother, paper mother, and the new bride of 1st Brother. Once the applications were completed, it was then a waiting game. However, 1st paper brother, his new bride, and his mother received approval soon after. They boarded one of the President Line cruise ships and sailed to America in 1949, while 2nd paper brother and I waited.

Life for a 10-year old in the countryside of Taishan was always adventurous. I did mundane farm work, put our small water buffalo out to pasture, or fished. I started school at the age of 9. The one-room school house, located in the next village, was for grades 1–4, and had a single school master. My parents paid the school master with bushels of rice. In those days, students were required to memorize the book contents word for word. To pass the test, you gave the teacher the book, turned your back against the teacher, and quoted the book verbatim back to the teacher. Study periods were a noisy affair as everyone studied their assignments aloud. We still used calligraphy brushes. Before one learned to write, the school master would make you hold the brush in a precise manner for what seemed to be hours, day after day. One time, I must have fallen asleep holding the brush. I got whacked in the head by the school master. Although tears rolled down my face from the hurt, I was too fearful to move or yell.

My paternal grandmother, whom I loved the most, must have been a strong person of will. She raised my father by herself. Being her favorite and only grandson, she carried me as a baby on her back while doing farm work. Whenever she carved-up a chicken or duck, she’d quietly call me over to put a favorite morsel into my mouth. I am very upset that I’m now unable to visualize her image. At the age of 15, I was crushed after receiving a letter informing me of her passing.

In our small village, I can count a number of mothers living alone with their sons as their husbands had gone overseas. This was also the case for my grandmother. She married, had a son, while her husband went overseas never to be heard of or seen again. My grandmother owned a couple of plots of small rice paddies. She farmed, gardened, and was self-sufficient. My father had to find work in his early teens. He became a merchant and was able to earn and save enough money to buy a couple more pieces of farm land. This became troublesome after the communist takeover as my family was labeled as landlords and suffered much pain and humiliation. We were not really a well-to-do family.

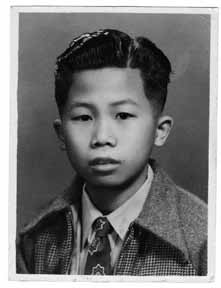

Photo courtesy of the Wong Family.

The Time Is 1950

The Communist Party had taken over China. Our schools switched from reciting Sun Yatsen’s Farewell Address to singing the Communist Anthem and political slogans. One night, my parents sneaked me out of our village. My father and I made our way to Hong Kong to wait for my immigration to America. We lived with my paper father’s relatives in the Wan Chai district 灣仔區 of Hong Kong. In the 1950s, Wan Chai was the red-light district.

Hong Kong, in 1950, with a population of 2 million, was bursting at the seams. Refugees from mainland China were everywhere. Squatters occupied the hillside and rooftops. For a 12-year old boy from the country, it was an eye opener. Neon lights and skyscrapers were everywhere. There were movie theaters and tall “white devils” in uniforms and boots marching in unison down the streets. My father was unemployed. We’d roam the streets day and night, sometimes getting propositioned from street walkers. We’d window shop at the big department stores in the Central District. We’d walk from one end of the island to the other end, since we could not afford the 15 HK cents to ride the double decker street cars.

We lived in a 3-story building that was all rented out except for half of a flat on the second floor. The front half was a carpenter’s shop, and in the back half, the owner partitioned two small rooms and a kitchen for themselves. He had a wife with two daughters plus a younger concubine with one daughter. In the hallway under the stairwell was a small wooden bed where my father and I stayed as boarders. I was enrolled into a school for a short time, but I had a hard time because of dialect differences. Late at night, there were the wonderful aroma of bread being baked at a nearby bakery, the music of classical Cantonese opera being played loudly on a phonograph from somewhere across the street, and the distinct sounds of mahjong tiles being shuffled! There was no refrigeration, but an open market was next door with everything fresh and live. One could eat in many of the food stalls squatting or sitting on the wooden benches. It was two blocks from the police station and the harbor. At the harbor, one could buy live rock cod, a favorite dish of Hong Kong locals, direct from the boat people. There was a small football field nearby, where soccer was played during the day. And at night, that place transformed into a wonderland with stand-up storytellers. My favorite stories were the old classics of Shaolin heroes. Professional chess players can be seen playing against multiple challengers at the same time. Vendors made all kinds of street food readily available. It was also a pickpocket’s haven!

My “coaching book” was getting worn from over exposure. Although I knew it was all a lie, at no time did I feel any guilt that I was doing something illegal. We never discussed the trauma and loneliness of my task. It was understood that my mission was to rescue my family from poverty by working in America; it was to be my honor to carry out this duty. It would be thirty years before I saw my birth parents again. At our reunion, I asked my mother what her feelings were about having her only son, at age 13, sent away. She said, “What do you think?” Later, she told me I had become a foreigner. That was also the price paid!

To America

In March of 1951, we finally got an appointment with the U.S. immigration in Hong Kong. Of course, we were excited and anxious, having waited 3 years for this moment. Much of that day remains a blur. I recall being ushered into different rooms. I was asked questions pertaining to my paper family, some legitimate and some mundane, and I answered them correctly. I was asked to draw the layout of a certain house of my paper family. Even though I had lived there, I was not prepared. I think I drew some squares. After leaving the Immigration Office, my paper brother and I compared notes. We collaborated well, but our drawings were erratically different. We thought we had blown it.

Second paper brother was the nephew to our paper father. He was actually 2 years older than his papers while I was 15 months younger than what I claimed to be. In appearance, there was a big contrast between us “brothers”. I had the dark tan of a country boy, while he was from the city and had attended high school. Perhaps the immigration officials turned a blind eye.

Days passed; our deadline was drawing nearer and nearer. Finally, we received a notice to appear at the Immigration Office at 8:00 am. We were all ushered into a waiting room. We waited anxiously until after 5 pm, without lunch. At one point, I saw another applicant hand a large envelope to an office worker; I believe they were waiting for our bribe. But we were not prepared and had no money. Just before the office closed, we got the necessary papers!

On April 16, 1951, 2nd paper brother and I boarded the SS President Cleveland. I said goodbye to my birth father without much fanfare. Turns out, it would be 30 years before we got to see each other again. Had I known, I may have treated that moment differently. His emotions were well hidden. The most upsetting is that I did not have a chance to say goodbye to my grandmother nor my mother. For the next 19 days, my paper brother and I were two lost souls stuck in separate first-class cabins. As we were so late in confirming our departure, our 3rd class reservations were sold by the cruise company. We had to board this ship as my 2nd paper brother had to reach American soil before he turned 16 years of age.

Being in 1st class should not have been unpleasant except no one spoke Chinese. We spoke no English; we never even held a knife and fork before. At one point, we ordered plain rice with catsup for our meal. Luckily, a Chinese lady traveling with her daughter took pity and ordered meals for us. What an adventure for a 13-year old! When I saw everyone put on life jackets, I thought the ship was sinking. I had no idea it was a safety drill. On top of it all, I was seasick. On the 3rd day, the ship docked into Japan. 2nd paper brother and I disembarked and wandered into the city alone. As soon as my feet landed on solid ground, the seasickness was gone. I was fine for the rest of the voyage. I ran all over the ship, used fireplace accessories as imaginary swords, and developed my skills in ping pong.

On May 4th, the ship docked in San Francisco. By this time the Angel Island immigration facility had been destroyed by fire. We were quarantined at another immigration detention center. We were assigned to double bunks in a huge open room full of male detainees. The windows were barred and the walls were dirty white. This felt like a really bad place. Here is where you can get sent back. No one trusted one another, and there were all kind of rumors. Someone said that he had been detained here for years; he couldn’t go forward and had nowhere to return. With nothing to do all day, there were a lot of anxieties. The days went ever so slowly. Finally, we were called for our questioning. The interview was actually very easy with only a few questions.

On May 17th, paper father’s uncle, who had handled most of the immigration legal work, picked us up. He took us directly to his home. This was the first time I had ever seen a bathtub. Grant Avenue, San Francisco, was much like Hong Kong, busy with eating places, medicine herb shops, bars, and Chinese spoken everywhere! The next day at one of the herb shops on Grant Avenue, 2nd paper brother met his birth father. He was a jolly kind of man, working as a houseboy for a doctor’s family near the Golden Gate Park. It may have been a little awkward for 18-year old 2nd paper brother to meet his father for the first time. But I had no problems as he gave me a big hug, rubbed his whiskered face against mine, and treated us to an Ice Capades show. The lights, costumes, ice dancing, and comedy were spectacles I had never seen before!

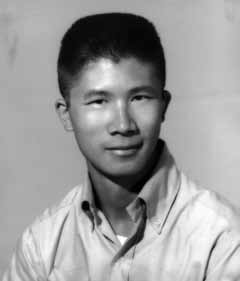

High school in Phoenix.

Photo courtesy of the Wong Family.

On June 6th, my paper parents came to San Francisco to take me to Phoenix, Arizona via my first ever train ride. We were all happy this immigration venture was over and successful. At 13 years old, I was in America with a deep ingrained hunger to succeed. But I did not know what to expect. My paper father appeared to be happy and upbeat. But he was not one for praise. Years later, I asked him about it and he simply replied, “When a good job is done, there is nothing to say.” He became my mentor and the biggest influence on my life. He encouraged me to keep up my Chinese language by reading his China Daily newspaper published in San Francisco. I had met paper mother in China; she was patient, caring and kind. She became like my real mother. She cooked, washed and mended my clothes, watched over me when I was sick, took lots of heat because of me, and became the buffer between paper father and me. Each Christmas, I would receive a shirt or a pair of Levis. The best Christmas gift was a brand new Huffy bicycle. I would use this bike going to elementary and high school.

Schooling in Phoenix

Like other new arrivals, I felt like a deer in headlights. I was given a common Christian name by our immigration attorney, and enrolled into a public school 3 blocks from the house. Because of my small physical size, I fitted nicely into the 4th grade. The only English words I knew were “yes” and “no”. I’d have never survived starting in the 8th grade. Being in the 4th grade allowed me the time to catch up on English. As I was more mature, this afforded me opportunity to excel in athletics, not be bullied, and become a leader. I was active in the student council and elected as Student Body President in the 7th grade. I was the only Chinese kid in school.

I would end up skipping the 8th grade and graduating from high school in 3 years. I attended a year of junior college while holding a 48-hour work week job at paper father’s grocery store. I envied my White friends for having the time and freedom to participate in after school athletics. I had to work off my immigration debt.

In 1957, my first car was a 1949 Plymouth! By this time, paper father’s two daughters had immigrated to America using the Refugee Act. They had studied English in Hong Kong and were enrolled in the same high school. I think paper father just wanted me to drive all of us to school. He added $300 for the used car to my tab.

About this time, I started to lose my Chinese. My correspondence to my birth father became fewer and further in-between. Soon, I was unable to compose a letter in Chinese. Today, I struggle to read a menu at a Chinese restaurant.

Hong Shan Doi

Overseas Chinese referred to their ancestral homeland as Hong Shan 唐 山.25 Those of us born in China were seen as hong shan doi 唐山仔. “Hong” (唐) sounds like the word for “sugar” so it was translated into English as “sugar mountain boys”. We were envious of the “ABCs”, American-born Chinese, or who chee doi 土纸仔, or “local paper boys.” The first time I saw a room full of ABCs was at a semi-formal dance for my first blind date with an ABC. It was a Phoenix Chinese community event organized by the Desert Jade Club.

In the Chinese American community, everyone knew I was a nephew and a paper son. For 30 years, in his letters to me from China, my birth father used my paper name instead of the birth name he gave me. Over and over, he urged me to respect and obey my paper parents. Not only do I owe my life to my paper parents, my father reminded me that our whole family was obliged. While I referred to my paper father and mother as my parents in the White world, I always addressed them in Chinese as uncle and aunt. There was an unspoken separation. I felt like a second-class citizen. I knew my place.

The warehouse, in the back of their store, had two partitioned rooms. One was an office for paper father, and the other with a folding cot was where I slept. Once the store closed at 9 pm, we’d all have dinner at the house. After helping with the dishes, I’d return to my corner of the world to do my homework. This was the loneliest of times.

When I was in the 6th grade, my homeroom teacher and coach wanted to take his basketball team to Arizona State University to watch and learn how the big kids play the game. Being the point guard of the team, I was excited but also nervous to ask my paper father to sign the permission slip. The next day at school, with tears streaming down my face, I stepped forward to return the unsigned permission slip. My paper father had said, “What is this nonsense? You are working after school.” I must have appeared dejected. Unbeknownst to me, my teacher drove to the store during the lunch hour and convinced my paper father to allow me to go. Of course, I was happy on the one hand, and anxious because I had caused paper father to lose face.

My paper father was the pillar of his clan. In the early days, the clan would all meet in his house for Sunday dinner after the grocery stores closed at 2 pm. Paper father did all the talking, and the others just listened and nodded. On one Sunday, he talked about taking his wife back to Hong Kong to visit her father, who is my maternal grandfather. The question was whether he would do his wife this big favor or save the money to send to Grandfather. This discussion went on for a while and somehow, paper father asked for my opinion. I murmured something like “Uncle, why ask me? You’re going to do what you want anyways.” Well, that was not the right thing to say. He was very angry that I had embarrassed him in front of others. For the next hour, his tirade was on. Our generation was not allowed to share feelings; no one was interested in my feelings.

My paper father and his brother owned two grocery stores with two check stands. But within six years, they would open a supermarket with five check stands. They became two of the leading Chinese merchants in Phoenix.

My paper father was a strong advocate of the Guomindang and bitterly against the Communists. The Communist destroyed his plans and dreams of one day retiring to the land he once loved. He would use other new legal immigration tools to help a dozen other relatives and clansmen to immigrate to America. He was active in Chinese civic organizations and was respected by the community. Above all, he valued his leadership position in the Chinese American community.

In 1996, he needed someone to accompany him back to Kaiping. I jumped at the opening. It proved rewarding for me because, for the first time, I felt like I was treated as an equal when he shared some of his inner thoughts on our flight. When we reached his village, the local school was closed for the day to celebrate and welcome him home. All the students were dressed up and singing songs to welcome him as we entered the village. When we reached the school house, there was his portrait hanging in the main hall. Little did I know, he had supported the school through the years. After retirement, I joined an organization that specializes in helping youth in LA Chinatown. I volunteer and try to give back a small amount whenever the need arrives. But in no way can I compare to the compassion and empathy displayed by my paper father towards his compatriots. Although he was my paper father, he was also a paper son himself.

Immigration Debt of This Paper Son

There were multiple means for paper sons to pay their way to America. For my 2nd paper brother, his birth father paid. He was one of the more fortunate ones. But most paper sons were like me, who paid by sweat and blood. I have never asked about the total cost of my passage, or whether there was any accrued interest, nor was I informed. But I do know that my papers cost $3000, and the voyage of the SS President Cleveland was $600. There were other legal expenses. In the 1950s, that was a sizable debt for me to pay off. The debt was a heavy load on my shoulders. My paper father told me he would deduct a certain amount from my pay each month—as he saw fit. Certainly, I had no choice in the matter.

At 13 years of age, in 1951, my pay was $5 per month. With time, my pay increased with the amount of responsibilities.

As they say, I started from the bottom. I washed toilets, swept the floor, cleaned the glass of showcases, sorted out empty soda pop bottles, and served as a box boy. With time, I learned every step of the grocery business from butchering to advertising.

In 1968, as I was leaving Phoenix, my paper father handed me an adding machine tape showing a debt of $300. I never paid that, and the subject never came up.

Phoenix to Los Angeles

I moved from Phoenix to Los Angeles and married an ABC who didn’t mind that I was a paper son. She was a school teacher, and I became a computer programmer. Later, I became an IT executive. We would have three sons.

Near that time, my paper father called to tell that there had been a whistleblower in the family. Someone in the clan has taken advantage of Immigration and Naturalization Services’ Confession Program. He revealed his clan’s illegal identities to receive amnesty for his real son, who got busted by Hong Kong Immigration years earlier. The cat was out of the bag! The INS now knew the truth about everyone in the clan. Sometime later, I’d received summons from the INS to appear in the Los Angeles office. I was brought into an integration room with a couple of INS agents. First, they asked if I needed an interpreter. After I said no thanks, they got me one anyways. Then the agent read me my rights. A blank piece of paper was placed in front of me. They asked me to write down all the aliases I have ever used. I wrote down my paper names, in Chinese and English, plus my birth name. I told everything about my paper family and my birth family. They found out I served in the US Air Force in 1962 after the Berlin Wall was erected. My existing US citizenship became null and void. However, the agents completed all the forms necessary to obtain another set of naturalization paper to become a new US citizen. I received my naturalization papers within six months. On May 1, 1970, I swore in again as a US citizen, now with my real name and birth date.

I then applied for my birth parents and my birth sister and family to immigrate to America. In 1980, Communist China finally released them. I was reunited with my birth family. We were all living in America, the land of opportunities and the land of the free.

Afterthoughts

I have lived a charmed life. I survived the Japanese invasion of China and missed the turbulent years of communism in China. I was too young for the Korean War and too old for the Vietnam War. I count my lucky stars every day!

Today, I am in my 80s living comfortably in retirement. I think about the hopes and dreams of my parents and the sacrifices they have made. However they could, our Asian American forefathers have fought against and survived racial policies and discrimination. The paper son story is part of that long ordeal. The fight is not over.

__________________________

25 Cantonese especially thought of themselves as of the Tang dynasty.