– Marian Lee Leng (1927– )

Marian Lee at 705 Bailey Street, Los Angeles. The house

was torn down during the building of the 10 Freeway.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Leng.

by Dr. William Gow

Marian Leng is part of a generation who lived in Los Angeles during the Second World War and her oral history exemplifies on a personal level the myriad ways that the Pacific War shaped the lives of Chinese American women who came of age in the city during the war. Like most Chinese American women in 1940s, Marian was American-born.36 Both her parents were as well. Born in Portland, Oregon in 1927, Marian moved to Los Angeles with her family in 1939 to work in China City. The family settled in East Los Angeles, a diverse community that included many Mexican American, Japanese American, and Jewish American immigrants.37

Marian was a student at Roosevelt High School when President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, incarcerating one of her best friends along with other U.S. citizens and residents of Japanese descent living on the West Coast. Because of restrictive housing covenants in Los Angeles, Chinese Americans and Japanese Americans often lived side by side, while attending many of the same middle and high schools. In 1940, the Japanese American population of Los Angeles was 23,321, nearly five times the Chinese American population.38 As such, Chinese American youth like Marian had ample opportunities to interact with Japanese American youth their age. Many Chinese Americans formed close friendships with Japanese Americans.

Like other Chinese American young women her age, Marian volunteered to support the U.S. war effort.39 At the age of 16, Marian met her future husband, who was a member of the Chinese military. The two met when Marian volunteered for the local chapter of the American Women’s Volunteer Service (AWVS). The AWVS was founded in 1940 before the United States entered the war, and eventually grew to be one of the largest wartime women’s support organizations in the United States. In Los Angeles, Chinese American AWVS members were responsible for founding the AWVS Chinese Center to help sell war bonds, and provide a space where Chinese American servicemen would feel welcome.40

Marian’s future husband, Git—or “Christopher”—Leng, was among a group of air force members from China who were stationed and trained at the Santa Ana Army Air Base (SAAAB) under the auspices of the Western Flying Training Command.41 Members of the Chinese military were sent to Santa Ana after Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s visit to the U.S. in 1943. The SAAAB became a favorite destination of local celebrities because of its proximity to Hollywood. These Chinese aviation cadets were at the SAAAB when Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, and Frances Langford performed to celebrate the base’s second anniversary in February of 1944.42

Marian and Christopher met as a result of her volunteer work at the AWVS Chinese Center. Located at 610 Spring Street, the Chinese Center was a converted grocery store that the AWVS volunteers scrubbed, cleaned, and painted before opening on 28 November 1942.43 China City shop owner, Dorothy Siu, was the president pro tem of the Chinese Center. In September of 1944, a second AWVS branch designed to serve military personnel of Chinese descent opened at 454 Jun Jing Road. Chinese aviation cadets from Santa Ana were among those present at the evening opening festivities.44 This branch was the New Chinatown Canteen. At the opening ceremony, Los Angeles Mayor Bowron stated that he hoped the canteen would not only serve “Chinese and other members of the armed forces but will also serve to bring the Chinese people and the American people closer throughout the war and thereafter.”45

Marian and Christopher kept in touch even after he was transferred to the southwestern United States to complete his training to fly B-24 bombers. The couple eventually married in the winter of 1944.

This oral history is composed of interviews conducted by William Gow and Heidi Li for the Chinatown Remembered project of CHSSC in 2008, along with an interview conducted by William Gow in 2019 and a written addendum to these oral histories by Ms. Leng. The interviews have been combined and edited for clarity.

My first twelve years were in Portland, Oregon. My parents had an appliance store. We sold toasters, fans, irons, light bulbs, and waffle irons. It was all electrical, because in the 1930s, that was all the rage. My father was a licensed electrician and did the repairs for the community. My mother ran the electrical store in the middle of Chinatown. We lived in bedrooms upstairs. The kitchen and bathroom were in the back of the store.

We moved to Los Angeles in 1939. My mother’s oldest brother, Uncle David Luck, had a shop in China City. In the newspaper clipping he sent us, he is selling an item to Mrs. Franklin Roosevelt. That encouraged my mother to come to L.A. Maybe business would be better than in a small community.

When we came to Los Angeles, the weather was warm and sunny even during the holidays. It was so different from the rain and snow in Portland. The streets and blocks were so long and beautiful, with stately palm trees. We lived in East L.A. We had a car in Oregon, but we didn’t have a car in Los Angeles. We had to take the streetcar from Brooklyn Ave. down to Main St. That got us to China City.

My parents had a store in the Court of Confucius. The shop was not open in the mornings because my father was a salesman for the Quon & Quon Import Company. His customers were in Olvera Street, China City, and New Chinatown. Our store in China City was well stocked with merchandise from Quon & Quon. Then in the afternoons, he would open his gift shop. Because it was up hill and you had to go on a pathway, business was not good. So my mother decided to work for a cafe down below called, Fook Gay coffee shop.

Later on, my mother became a partner in the coffee shop. She talked to the landlord and instead of five stools, she asked him to make it twelve stools; seven more places. I remember that place very well because I squeezed oranges there. For 10 cents, you get fresh orange juice and all you can drink. I never squeezed orange juice again after that!

Next to my parents’ coffee shop, there was a restaurant and then the gift shop. The gift shop was owned by my uncle. But because of the war in 1941, my uncle gave it to my mom, and he went to work for Lockheed. He was an engineer, so it was a better job for him than to be a shop owner.

I remember going to school in the morning, and the president telling us we were at war. On the Sunday before school, we had heard on the radio that Pearl Harbor was attacked. We all felt bad. We didn’t know what’s going to happen. America being at war was a shock. To know that we were attacked in Hawaii, that’s really something. We were afraid that we would not keep on living, and that the Japanese would come to America and bomb.

World War II to me was bad, very bad, because of the imprisonment of my best Japanese American friend, Yayeko. I missed her a lot. She and I were best friends, and we enjoyed school together very much. We watched the football games together. She and I got along well. She wrote and told me that the place where she was interned was very dusty and sandy. It was in the desert and she was so bored because they had no school yet. She had a horrible time.46

When World War II broke out, business in Chinatown City was good. When the war came, people had more money to spend because there were jobs in the aircraft factories and the shipyards. China City was like a recreation area. It was free. You could eat in the restaurants. You could buy things in the gift shops. And a lot of people didn’t want to cook at home, so they would come to the restaurants. The food was good and cheap. We had rationing. We had to save our coupons so my mom’s coffee shop would have enough beef for the burgers. Sugar, coffee, all that was rationed because we had to remember our troops.

Marian Lee and Christopher Leng in November 1943 in Boyle Heights. Christopher was born in Guilin, an alumni of Wong Bo military academy, and member of the Chinese Air Force.

Photo courtesy of son, Jeff Leng.

We also had the Chinese Canteen. It was started in 1942. Dorothy Siu started it. She got the community together. Her apartment was in China City; in fact, it was across from my mother’s coffee shop. So I knew her real well. This Chinese U.S.O. was very popular. We girls managed that. Many servicemen from the Army, Navy, and Air Force would frequent the U.S.O. The Canteen was very popular because the men could come and visit, and have coffee and doughnuts. The doughnuts were given to us by the bakery for free. It was a good advertisement for them. We had a lot of movie stars that would come and entertain us like Bob Hope, Jerry Colonna, and Frances Langford. I remember they were very friendly.

All the local junior high and high school girls would come. Anyone could volunteer. All you had to do is serve coffee, tea, and doughnuts. You know, just be friendly and talk to everybody. And at that time, it was very exciting because we were representatives of the Chinese community. We all volunteered our time. Nobody got any money. It was interesting because I met boys—mostly Chinese—from New York, Chicago, from all over the United States. My mother would let me go on the weekends for a few hours from the restaurant, to help serve the fellows.

In fact, when the U.S.O. hosted the officers from the Chinese Air Force, my friends and I accompanied them to the movie studios, and lunch and dinner at the Biltmore Hotel downtown. My husband was a lieutenant already. They were all young men in their 20’s.

When the order from Madame Chiang Kai-shek came to send the officers, we were all excited and said, “Geez, we’re going to have some of these fellows coming!” And then the woman who ran the canteen said, “Well, only the older girls can go—those eighteen and up.” My mother said, “That’s not fair! It’s the younger girls from 16 to 18 that do all the serving. The older girls only stand around talking to the guys.” My mother fought for us younger girls to go. I was 16.

Oh, that was exciting! They were all in their uniforms and they were all so good looking. Oh my god, that’s going to be a fun day! What a date! We’d have dinner at the Biltmore Hotel afterward. I was very fortunate because I can speak Cantonese and English very well, and I knew Mandarin, too. So, I was very popular. That stood me very well with all the fellows because they wanted to talk to me. This one fellow was very shy. It was getting hot, so I took off my coat. I had one of these red jackets on, and he says, in Chinese, “Can I hold it for you?” I said, “Well, if you want to.” So, I just handed the jacket over to him.

In the bathroom, my girlfriend said, “Hey, that guy likes you. He’s holding your jacket for you.” I said, “No… god, just somewhere I can hang my coat.” I laughed about it. We sat with him at the dinner table. We all had our pictures taken. He found out my name, my phone, and where I lived.

Sunday morning, the doorbell rings. I look out the door, “Who the heck is this in the uniform?” And he’s looking for me! It was 10 o’clock in the morning! My father was just barely getting up because we open our shop until 10 in the evening. We had to take the last streetcar to East L.A. And then we had to walk four long blocks home at night. My father and mother were all so dead tired from working those hours at the restaurant and the gift shop.

So then, he wanted to do something. He said, “What would you like to do?” I said, “I want to go see a spooky movie.” Can you guess what it was? Phantom of the Opera! That was scary… Oh, my god! That is how I met my husband.

Marian and her Chinese Air Force husband-to-be, Christopher Leng, on Thanksgiving Day 1943, on Bailey Street in Boyle Heights. Sandwiched between is Marian’s mother, Elsie Luck Lee, who was “gaining a son rather than losing a daughter.”

Photo courtesy of son, Jeff Leng.

____________________

36 According to the US census, 72% of Chinese American women were US born in 1940 compared with only 44% of Chinese American men.

37 George Sanchez, “‘What’s Good for Boyle Heights is Good for the Jews’: Creating Multiracialism on the Eastside in the 1950s,” American Quarterly (2004), 137.

38 Sixteenth Census of the United States: Population, 1940: Characteristics of the Nonwhite Population by Race, 97-99.

39 Mary March Brown, “The Chinese Add to Laurels,” Los Angeles Times, March 22, 1944, A4.

40 Marjorie Lee, “Coming of Age: Chinese American Women Doing their Part,” Duty and Honor: A Tribute to Chinese American World War II Veterans of Southern California (Chinese Historical Society of Southern California, 1998), 49.

41 When Git met Marian’s mother, Elsie Luck Lee, for the first time over Thanksgiving dinner, Elsie wanted him to have an American name. Elsie thought that “Git” sounded like “Kit” and was reminded of the famous American mountainmen, Kit Carson, whom Git admired in Hollywood films. Elsie looked up Kit Carson in the encyclopedia, and discovered that his given name was Christopher. From then on, Git Leng was known as Christopher Leng. As told by son, Jeff Leng, in correspondence. On the SAAAB, see “Air Training Era Closes,” Los Angeles Times, November 14, 1945, A2.

42 “Leeside,” Los Angeles Times, February 17, 1944, A4.

43 Lee, “Coming of Age,” 49.

44 “New Chinatown Canteen Opened to Servicemen,” Los Angeles Times, September 19, 1944, 8.

45 Ibid.

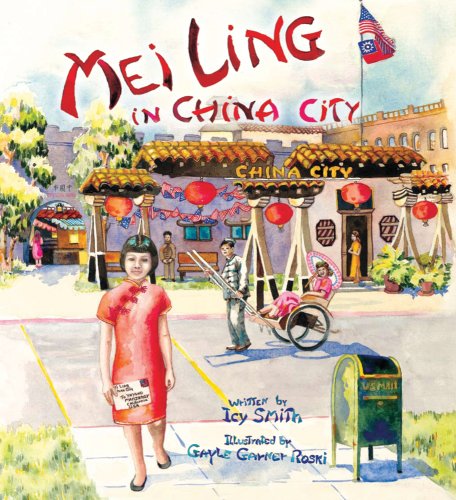

46 The story of Marian and her friend, Yayeko, is retold in a children’s book. See Icy Smith’s Mei Ling in China City (East West Discovery Press, 2008).