– Jim Wah Gee (1926–2004)

Jim Wah Gee was born in Guangzhou and served in the U.S. Navy in the Pacific Theater during World War II, including Iwo Jima. He had an illustrious career between 1954 and 1990 as an aeronautical engineer with North American Aviation and Rockwell International, working on the Apollo space missions and the Space Shuttle program. Gee was Chair of the Chinese American Welfare League, Los Angeles (1976-1978), Vice Chair of the Community Welfare Committee of Los Angeles (1973-1974), President of the Chinese American Engineers and Scientists Association (1971-72), Scholarship Chair of Gee Poy Kuo Association (1984+), and lifetime member of the American Legion. In 2009, Barack Obama nominated Dolly Gee, Jim’s daughter, to the United States District Court for the Central District of California. The U.S. Senate confirmed her by unanimous consent on 24 Dec 2009. She is the first Chinese American woman to serve as an Article III federal judge. This is from an interview with Marji Lee on 4 Jan 1997.

L to R: Ben Yi (Jim Wah’s distant cousin), George Gee (father), and Jim Wah Gee.

Photo courtesy of Duty and Honor.

I volunteered for the U.S. Navy in 1942. I thought if I fought for the United States, I would be fighting to help China. I’m the 27th generation of the Gee family. I was born in China but I came to the United States before I was 16. If you came to the U.S. before you were 16, you would automatically be a citizen if your father was a citizen. Before World War II, I was going to school in Taishan, China, but Taishan was being bombed by the Japanese army. Taishan High School was one of the most beautiful schools in the region, and there were overseas Chinese attending. It offered room and board. The students had to run away due to the bombings. My father said, “You don’t have a chance in China to fulfill your education so you might as well come to America to be a coolie.” I came right before Pearl Harbor on the last voyage of the SS President Coolidge out of Hong Kong. I had to travel through Japanese-occupied areas to get to Hong Kong. The coast was already blocked by the Japanese Navy. Soon after that, the SS Coolidge was sunk by mines. I now sponsor a scholarship for students at Taishan High School.

When I came to the United States, I knew a few abc letters, but I really couldn’t speak English. I stayed three months at the Russian Hill immigration detention center within the City of San Francisco. Angel Island was already closed. We were all Chinese at Russian Hill. I was 15, and most people were older than me. I felt we were treated like dogs. I didn’t think Chinese had much chance in America. But after I served in the military and got my education, I felt we’ve made a lot of advances. It is especially better for the younger generation.

The Gee Family Association helped me while I was at Russian Hill. I had an “uncle” who told my father where I was. My father bought me a train ticket to New York. I stayed with the Gee Family Association in San Francisco for a few days. Fortunately, I met a lo fan8 American professor who was just returning from China and was also going to New York. He had been teaching English at Chongqing. He spoke Mandarin. He helped me during my travels, but we lost touch soon after; I owe him. My father, George Yow Gee, lived in New York, and he was a “citizen” after the San Francisco earthquake. He was in the restaurant business. I think he came around 1920.9 When I came in 1941, we started manufacturing soy sauce as Hinlee in the Belmont section of the Bronx. Later my father moved the business— renamed Savoy Products—to Brooklyn. My mother, Kay Hing (Wong) Gee, came to the U.S. in 1967 after my grandmother died.

After about two years in New York, I joined the service. I was almost 18 so I thought I might be drafted. I’d rather volunteer and join the Navy. If they draft you, you would be in the Army. You had to be a citizen to join the Navy. My father said, “You fight for both countries now.”

I got good training but there were a lot of stereotypes. The recruitment office asked me if I wanted to be a cook or a washerman. I said, “What? I thought I would carry a gun and fight the Japanese.” I insisted. So they sent me to gunnery school, and I became a gunner’s mate 3rd class. I handled guns. I was small but with a gun, nobody dared to give me trouble (laughs). I didn’t want to be a stereotypical cook.

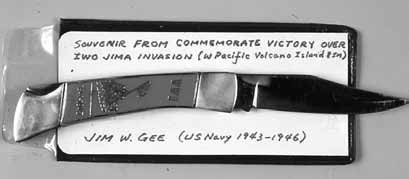

Commemorative knife from Jim Wah Gee’s collection.

Photo courtesy of Duty and Honor.

I went to boot camp for about two months. I got gunnery training at Norfolk, Virginia. That was about one month.

We picked up a ship in Boston. It was a converted LST (Landing Ship, Tank). It was converted to be a repair ship. I was a gunner’s mate on the USS Myrmidon. We went to Florida, Panama, and then to San Diego. Then we went to San Francisco, Hawaii, and Iwo Jima. We did repairs at the San Diego naval shipyard. We then picked up supplies and equipment.

I got along with most of my shipmates. Some of the less educated group still looked down on Chinese Americans. They had the feeling, “Why don’t you be a cook? Or a laundryman?” I said, “I came to fight a war, not to cook.” I’m still friends with this guy with a Latino background. They also were stereotyped. No matter how smart you are in the Navy, Asians didn’t have the political power. You were always less.

After the most bloody battle in Iwo Jima (Feb–March 1945), we went there to repair all the LST and other landing craft that had been knocked down. I was there. Our Marines had wiped out the Japanese defense forces. But we still saw some kamikaze bombers. Our B-29 bombers from Saipan Island would come out at night. Sometimes, they would need to make an emergency landing on Iwo Jima. Iwo Jima was an important stepping stone especially for these B-29s—and a stepping stone to Japan.

The atomic bomb was a good thing to the extent it caused Japan to surrender. We fulfilled our mission. We had thought we would have to make a landing in Japan. We called it Iwo Jima to Chichijima 父島 (literally, father island) and Hahajima 母島 (literally, mother island)—moving towards the “father” and “mother” islands before Honshu.

At that time, I was a gunner’s mate facing those Japanese bombers that wanted to destroy the airfields in Iwo Jima. I saw the fighters produced by North American Aviation, the P-51 Mustang. I thought, “Wow, these airplanes are powerful and impressive.” I thought North American would be a good company to work for. After I came home and finished my aeronautical training, I worked on the North American P-51 to F-86 Sabre to XB-70 Valkyrie to Apollo and to the Space Shuttle. I worked 36 years for North American Aviation and Rockwell International. Now it’s called Boeing North American. It extended from my military service to my civilian life.

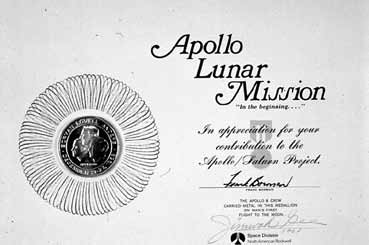

Recognition of Jim Wah Gee’s aeronautical engineering career, 1968.

Photo courtesy of Duty and Honor.

I was 20 after I got discharged from the Navy in 1946. I was taking high school classes in the evening at the State

University of New York. I went back to Hong Kong to marry Helen Baoxing Chan Gee. I was still working with my father making soy sauce. This guy from the Gee Family Association told me to come to California; he said, “It has good weather.” The pictures of California were very impressive. The “mayor” of Chinatown, Sam Ward Gee, would send me a letter each Christmas to ask me when I was coming. He even sent me a California orange (laughs). My father was against my coming to California. When we left, I told him I was going to be independent and never spend one penny of his money. After the war, imported soy sauce became cheaper, and my father’s business faltered. Later, my brother got a civil engineering degree in Missouri. He worked for the California state highway system. When my father died in 1969, my brother and I were not interested in continuing the soy sauce business.

My wife and I came to Los Angeles in 1951. I took the trolley car from Long Beach to Union Station. Sam Ward Gee had the Kwan Lee Lung liquor store next to Union Station. Sam was also in the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association. In 1953, I finished my education at Inglewood’s Northrop Institute of Technology in aeronautical engineering. I used the G.I. Bill. I remember that gave me $110/month. At night, I went to work for some extra funds. We already had a baby.

Those of us in World War II service were the first generation of Chinese Americans to work for the military industry. We did our best, and now they trust us. Prior to that, no matter how high your education or skill, they wouldn’t hire you. This was a first step towards education and an occupation.

I had to fulfill my father’s dream. He wanted my brother and me to become a doctor or a lawyer. Because of the war, I did not do it. I became an aerospace engineer; I was so impressed with how decisive air power was in World War II. I did, however, pass my father’s dream to my son and to my daughter. My son, Kelvin, is a doctor of pharmacology and a professor at UCI. My daughter, Dolly, is a union labor lawyer. I didn’t have a chance in my time to fulfill my father’s dream, but the next generation keeps fighting for equality. My daughter works for labor rights.

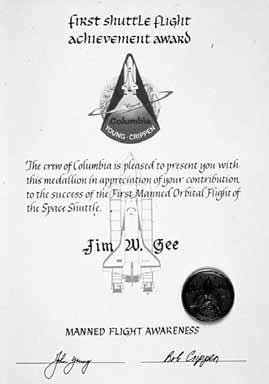

Columbia was the first shuttle to reach space in 1981.

Photo courtesy of Duty and Honor.

We Chinese Americans have a very humble background. When I was with CHSSC’s Irvin Lai at the old Chinese cemetery at Evergreen, I thought of my great-grandfather’s brother. He came to the United States near the 1850s. He was killed either in the gold mines or as a laborer, but we could never find his remains. I still haven’t found his remains, but it is important to remember him and our background. It touches my heart. We Chinese Americans still have a long way to fight for equality. In the 1850s, that generation came to the United States but they had immigration problems, and many had to return to China. They faced discrimination. There wasn’t that much opportunity here in California. After 1875, they wouldn’t even allow Chinese women to come to this country. We had to do something against all these restrictions. So now we have the power to vote. Do young Chinese Americans even know about the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act? We better know our own history. Our background was so humble.

Nobody is going to tell me that I’m not as American as anybody else. Except for the American Indians, we are all from foreign countries. For the kids, you have to fulfill your educational goals. Then you have to do something for your people.

When I heard that Gary Locke became the elected governor of Washington state, I felt he fulfilled our dreams. His ancestors worked on the railroads and the gold mines. One day, a Chinese American will become the president of the United States.

I’m still a “Chinaboy”. I remember JFK’s words, “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” We Chinese Americans should always remember that.

___________________

8 Cantonese slang meaning “Caucasian.”

9 After the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, the Hall of Records was destroyed. Many Chinese Americans then claimed they were American citizens by birth. But if George Yow Gee came near 1920, he was more probably a son or a “paper son” of a Chinese American who had claimed citizenship.