By Margie Lew

(On Sept. 22, 1978, five members of the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California – John Yee, Humberto Rivera, Hwei-Chu Meng, Albert Lew and myself – had the rare and exhilarating experience of interviewing Mr. Lim Poon, Chinese merchant seaman who holds the world’s record of the longest survival alone on a raft – 133 days, or almost 411, months. The Society is proud to dedicate this special edition of the GUM SAAN JOURNAL to Mr. Poon, a man of great courage, and a rare human being.)

Daybreak over the Atlantic on the morning of November 23, 1942 was no different from that of any other morning. Or so it seemed. However, within a very few hours, a fateful turn of events would touch the lives of many persons, in particular one Lim Poon, steward on the British freighter, the U.S. Ben Lomond. Lim Poon could not know that a series of circumstances would ultimately place him in an indisputable status in both the Guinness Book of Records and Robert Ripley’s “Believe It or Not”; nor could he know that in the near future he would receive a medal from the British government; special recognition from the United States Congress; acknowledgment by the National Geographic with a story published in its May 1945 issue.

On this particular November morning during the early years of World War II, the Ben Lomond was sailing on the Atlantic, 15 days out of Capetown off the African coast, en route to South America. Some time between 11:30 and noon, the ship was torpedoed by an Italian submarine, causing it to sink within minutes. Luckily, Poon managed to get into his lifejacket before being sucked under by the swirling waters. After what seemed a lifetime, he was propelled upwards, and found himself one of several crew members drifting about in the water. Spotting a raft with five men on board, he started to swim towards it. At that point, the submarine surfaced, took the five men in for questioning and returned them to the raft. The Italians ignored Poon’s pleas for help, leaving him to fend for himself. While floating for an hour, Poon saw an unoccupied raft in the distance. After a long, hard swim, he managed to climb in, exhausted but safe. By this time, none of his fellow crewmen were in sight. He was now alone in a vast expanse of ocean with no means of rescue or assistance.

Question: Mr. Poon, were you a good swimmer at the time?

Poon: No. I could swim just a little. I found a hatch board, and hung onto it until I saw the empty raft.

Question: What food and supplies were there on the raft?

Poon: Six boxes of hardtack, 2 pounds of chocolate, 10 cans of pemmican (a concentrated preparation of dried beef, flour, molasses and suet), 1 bottle of lime juice, 5 cans evaporated milk and 10 gallons of water. Also, there wre four poles and a tarpaulin, strips of canvas, 2 paddles, signal flares anq smoke pots, a can of massage oil, a flashlight, rope, and 2 tanks for food and water.

Question: How long did the food supply last?

Poon: About 50 days.

Question: After your food was used up, how did you survive?

Poon: By planning ahead. I had so much time to think about what to do when the food was gone. I caught fish by using the spring from my flashlight as a hook. If I caught a small fish, I would use it to catch big ones, and I caught quite a few 20-poundersl If I ran out of bait, I used barnacles which were clinging to the sides of the raft. I cut the big fish in strips and hung them in the sun to dry. The dried fish attracted birds, which I caught and ate as a change in diet.

Question: There were 10 gallons of water on the raft. When that was gone, how did you obtain water?

Poon: I used the tarpaulin to catch rainwater, whenever possible. The tarp was fastened to poles at four corners of

the raft, with one end lower than the other to let the water run into a container.

Question: What helped you to survive this terrible ordeal?

Poon: I never gave up hope that everything would come out all right, that someone would find me and help me.

Each day I told myself – “Maybe today someone will see me. ” To keep my mind busy, I thought of my parents and other members of my family; I re-lived my boyhood years on Hainan Island in Kwangtung Province where I was born; I

made plans for the future. I did some praying, too, but mostly I would not let myself lose hope that some day I would be rescued. By “using my head,” I was able to keep my mind alert by thinking of things to do.

Question: What kind of things?

Poon: Making my own tools, such as fish-hooks, fishing tackle, and a knife made from the tin of a pemmican can.

Question: How did you keep your sanity during this long period? Do you think your Chinese ancestry had anything to do with your ability to survive?

Poon: Being Chinese probably had something to do with it. China and the Chinese people have suffered through wars, starvation, and many hardships, and still survive today. But I think that people of other nations also have the ability to endure. Remember that we are all part of the human race. Another thing that helped me to survive was the fact that I was alone. When there are twp or more persons together for a long period of time in a desperate situation, someone could possibly become panicky, sick, or lose his mind. This causes fighting, accidents, and even death. Since I was alone, I had only myself to consider. My health, both mental and physical, was my own responsibility.

Question: Did you become sick at any time or experience any bad effects from the sun or the weather?

Poon: No, I was very lucky to be able to keep well, probably because I was young and in good health at the time.\

Question: Did any ships come close to your location?

Poon: Yes. After the first week, I saw a freighter in the distance. I used the smoke pots to attract attention. The crew must have seen me, because the ship came within a mile, but they did not pick me up.

Question: You must have felt very sad about this. What were your thoughts at this time?

Poon: Yes, I did feel bad when the ship turned away, but I had already made up my mind that whatever was going to happen to me was not in my hands.

Question: Was there any other time that you could have been rescued?

Poon: About the 100th day on the raft, I saw a formation of six planes, and I signalled them. One place came down to investigate, but did not try to pick me up, probably because of rough seas.

Question: What were your feelings about this?

Poon: I was disappointed, of course, but what could I do?

Question: In your own mind, what were the reasons you were not rescued in both instances?

Poon: Since it was a time of war, it would have been dangerous for anyone to try to pick up just one person, not even knowing if he were a friend or enemy. Anyway, that was how I tried to think, in order to keep myself from feeling too disappointed. I still would not give up hope that someday I would be rescued.

That “some day” finally came on April 5, 1943 when Poon was sighted by a Brazilian family in their small fishing vessel 50 miles off the coast of Salinopolis, Brazil. By this time Poon had been drifting alone for 133 days across the Atlantic, a record that in all probability will never be broken. His physical condition was such that he was able to walk off the raft unassisted, which is also a record in itself.

Question: Mr. Poon, what happened after the Brazilian family picked you up?

Poon: We could not communicate very well, since they spoke only Portuguese, and I only Chinese, but I was able to make them understand what had happened. Besides, they could see by my appearance and the condition of the raft (which was made in Hong Kong), that I had been on the ocean for a long time. The family took good care of me

for three days before returning to shore.

Question: Your relief and joy after being rescued must be difficult to describe. What happened when you went ashore?

Poon: I asked for the British Consul, giving him my name and the name of my ship. After checking the records, the Consul informed me that I was the only survivor of the Ben Lomond. I stayed in the hospital for 35 days, then left Brazil (by plane) for Miami and New York. The Chinese Consul found a job for me as a mechanic with the Wright Aeronautical Corporation of New Jersey. When World War II ended in 1945 the plant closed. I went back to sea, and have been there ever since.

Question: The Guinness Book of Records mentions that you received a medal from the British government. When did this occur?

Poon: In July 1943, I was flown to England to receive the British Empire medal from King George VI in Buckingham Palace.

Question: Were you a Chinese citizen at this time?

Poon: Yes, but now I began thinking of becoming an American citizen. My friends asked Senator Warren Magnuson for assistance in this matter. In July 1947, President Truman signed a special bill to let me apply for citizenship. In 1952, my final papers were completed. This made me very happy. Now I would not have any more problems with the immigration people!

Question: A newspaper article mentioned that you were asked to help the United States Armed Forces with their survival training program. How was this done?

Poon: From drawings I made, the government was able to build a raft like the one I used. I told them about the different ways to get food and water, how to keep out of the sun, and how I made my own tools.

Question: When you are not at sea, where is “home”?

Poon: My wife and four children live in Brooklyn, New York. Our three daughters are college students. Lillian, 22, received a scholarship in IBM marketing, and attends New York University; Linda, 21, also enrolled at NYU, is studying law; Janet, 18, is a student at Brooklyn College, but will be going to the University next year; son Georgie, 16, is in his last year of high school, and will be going to college after graduation.

Question: What is your present occupation?

Poon: I am Chief Steward on the United States Lines cargo ship, the S.S. American Lancer. We sail the Pacific Ocean, stopping at Honolulu, Guam, Hong Kong, and Yokohama. On the west coast, we dock in Oakland, Long Beach, and San Diego. We pass through the Panama Canal on the way to the east coast, stopping at Savannah and New York.

Question: One last question, Mr. Poon. How many times have you been interviewed about this experience?

Poon: Only once. In 1945, Look Magazine talked to me, and wrote an article, which they sold to the National Geographic.

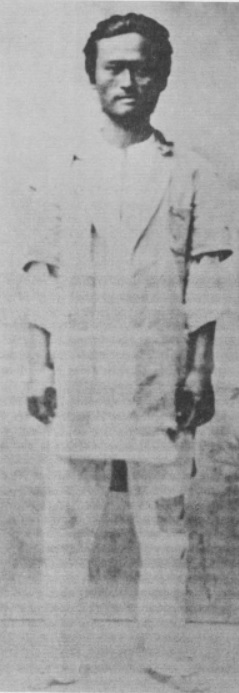

When Lim Poon was experiencing his ordeal at sea, he was a young man of 26 in excellent physical condition. Today he is a youthful-looking 62 with a sparkle in his eyes that indicates he has lost none of his spirit or zest for living. His mind is alert as ever; his memory of past incidents is keen and clear. An unswerving faith in his fellowman has not diminished through the years. Poon’s will to survive in spite of insurmountable odds has earned a special niche for him in the history of world events. His endurance and resourcefulness has generated a feeling of high esteem in the hearts of his Chinese countrymen, who proudly claim him as their own. Equally significant, however, is the fact that his courage and indomitable spirit shine forth as a beacon of faith and hope to all men everywhere – he is truly a champion among champions in the brotherhood of man.