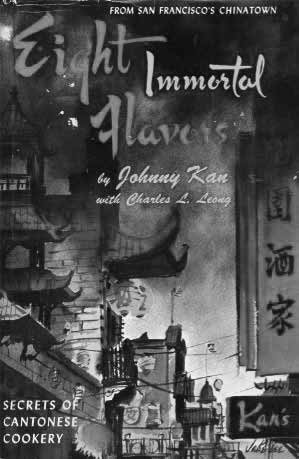

by Johnny Kan and Charles Leong

A few years ago, the Museum of Food and Drink in New York City opened a wonderful exhibit entitled “Chow: Making the Chinese American Restaurant.” Featured prominently in the exhibit was the book, Eight Immortal Flavors: Secrets of Cantonese Cookery. This 1963 collaboration between Johnny Kan and Charles Leong earned an introduction from James Beard, the namesake for the James Beard Award of culinary arts.

Johnny Kan (1906–1972) was a San Francisco institution. In 1935, he managed Fong Fong bakery and soda fountain, and invented “Chinese flavored” ice cream like lychee and ginger. In 1939, he opened Cathay House and then in 1940, Chinese Kitchen—that delivered. In 1953, Kan’s opened at 709 Grant Avenue and then in 1968, Ming’s in Palo Alto. Johnny provided his reputation and his recipes for the book, Eight Immortal Flavors.

James Beard writes in his foreword on p. 6, “Charles Leong, John’s old friend and collaborator, is a writer who has contributed to and researched for Reader’s Digest, Sunset Magazine, Ford Times, and many other publications. An authority on Chinese life in America, he now is an editor of the Young China Daily, a San Francisco Chinatown newspaper founded by Dr. Sun Yat-sen, father of the Chinese republic. He is a gourmet and an excellent amateur cook. Some 20 years ago, when Charles was editing the Chinese Press, a Chinese-English language newspaper, John Kan prepared a series of articles for the paper entitled ‘The Romance of Chinese Food.’ Thus began the germ of an idea.”

Eight Immortal Flavors is a delightful and informative culinary book. In the chapter entitled “Rice, the Eternal Chinese Question” with recipes for steamed rice a la Kan, naw mai lop chong fon (glutinous rice with Chinese sausage), ngow yuke fon (beef rice casserole), etc., there is a three-page culture lesson including this paragraph on p. 75:

Rice has been a staple food of the Chinese since time immemorial. Prior to 1914, rice from China entered the United States duty free. Through the years and through several wars, it has reached the situation where all rice consumed by the Chinese is grown in the United States. The majority of the Chinese in America live in California—and today, most of the rice they eat is grown in Texas. The Lone Star state produces a long grain Patna-type rice which cooks into separate grains and is most akin to the old native type.

This excerpt from Kan and Leong’s section entitled “Gourmets of the Golden Hills” on pp. 27–30, not only show their early 1960s awareness of affirming Chinese American history, but Leong’s beautiful lyrical style of writing:

The golden enchantment of California in 1849 brought Chinese as well as men from other parts of the globe to the Golden State. With a fine sense of poetry and realism, the Chinese in their native tongue spontaneously referred to their new home as Gum Shan, or Golden Hills. For more than a century, San Francisco Chinatown has been the center of the world of Gum Shan…

San Francisco, for the Western hemisphere, is truly the paradise of the Chinese epicure, and is second only to Hong Kong. The Chinese population in this city by the Golden Gate is the size of the modest American city—50,000 persons. Half of this number lives in the Native Quarter known as Chinatown, a “city within a city” of many moods and intrigues, including even a temple rooted in its founding location of over a century ago. Within its Quarter, Chinatown serves every need and desire of the human being, from stomach to soul, from birth to burial. Like eternal Rome, Chinatown is the center of its world. Chinese from all over America make a pilgrimage to Dai Fow, which means emphatically The Big City, or San Francisco (Chinatown).

Here are located, either on the main thoroughfare Grant Avenue or on Waverly Place, the “Street of Balconies,” most of the national headquarters of the family associations, founded by the Cantonese emigrants who came here first to mine gold, then to build the railroads, to work the farms, and to contribute greatly to the growth of Western America. These are the Chans, the Wongs, the Lees, and the Quans, and others who now live all over the United States—perhaps in New York or in Cucamonga, California—but wherever they are, most have friends or relatives, or official family ties in San Francisco. Some 90 percent are Cantonese, emigrated from the province of Canton.

All civic, cultural, education, religious, social and business activities of the Chinese gravitate around San Francisco Chinatown. In early summer, the glutinous tri-coned stuffed puddings mean Dragon Boat Festival time. The partaking of moon cakes is Moon Festival time and the wonderful climax of the year—Chinese New Year—mean gourmet feasts for everyone. Every holiday is a feast day. The Cantonese love to eat. The holidays furnish a good excuse to do so…

The eight immortals have been part of Chinese culture since the Tang and Song dynasties.

Photo by Joe Mabel (2008), CC-BY-SA-3.0