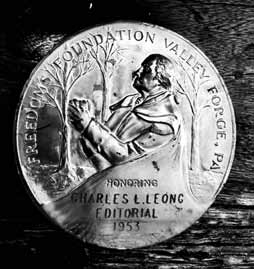

by Charles L. Leong

Editor’s note: The Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge was established in 1949 to “educate about American rights and responsibilities, honor arts of civic virtue, and challenge all to serve a cause greater than themselves.” Their juries sift through thousands of applications for their National Awards— given on Washington’s birthday—“without concern for race, creed, color, or political party.” Charles sent this winning entry to Freedoms Foundation on 10 November 1952.

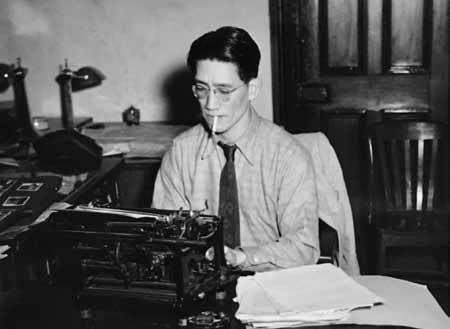

Photo courtesy of the Leong Family.

I am a receding forty. I have a lovely wife, Mollie—and Rusty, two years old. Rusty is rough and ready, a real all-American boy. Me? I pat my widening waistline and console myself that life begins at forty. I congratulate myself that my particular span of forty summers include in my memory the faint strains of “Over There” and the Kaiser being hung in effigy in our sleepy country town; my own tired feet marching in the dust of many countries and campaigns in World War II: and now, to wonder as to the why and how and when of the embittered battling in the hills of Korea.

These have been my fateful, fruitful years, and while still this side of midcentury, I sense that I am a part of the great destiny of America which is forging ahead—sometimes hesitantly, sometimes naively, sometimes brashly and a little arrogantly, but always generously and kindly and courageously.

I am an American of Chinese ancestry. I am a part of this America and its destiny. I am young enough to have escaped being a political scapegoat of the 1880s, when the cries of minorities’ persecution were “The Chinese Must Go!” I am old enough to have played a small part and to have relished with pride the generous praise and support given by my fellow Americans to my race during its courageous stand in World War II. I am mature enough now to stand with firmness and conviction when some hysterical Americans flaunt wildly that since China’s Moscow-inspired and directed masses are in deathly grip with our American boys in Korea, all persons who look Chinese, and are Chinese in racial origin, must be Communists.

To them I say simply, with pride and conviction, “I am an American.”

Every September, I participate in the installation ceremonies of my American Legion group, Cathay Post #384 in San Francisco. When I look at the faces of my fellow Americans of black hair and Oriental [sic] mien—as we recite the preamble to the Legion Constitution “to uphold and defend the Constitution of the United States…”—I sometimes think of the phrase “Chinaman’s chance” used disparagingly and/or ignorantly by many persons. I look around at my comrades-in-arms—some who came from China as young lads, some of them second or third generation Americans. Some remained privates. A few became colonels. Some were Purple Heart combat vets. Others never went overseas.

But we are all good Americans.

And, if you please, they had a “Chinaman’s chance” to become good Americans. To me, “Chinaman’s chance” are not two abstract words. I have lived with them. Neither is my story new nor novel. In fact, its universal quality is the very point which may make the telling worthwhile.

I am a newspaperman, a college graduate with what I hope is a future still ahead of me. [I am] the average man—with the average American’s dream still contained in me. I pay my taxes. I owe bills. Some of my suits are frayed. But my memories are not. As a newspaperman, I am supposed to be articulate, at least on paper. And in exploring the trails of my memories—from the almost forgotten horse-and-buggy rides of my childhood to yesterday’s roar of a jet-fighter—I come across landmarks in my own “Chinaman’s chance” which add up to the conclusion that because of the American way of life, it has been a pretty good chance.

Yes, as an American of Chinese background, I have had my share of rebuffs in jobs and housing. I would be hypocritical and dishonest to myself and to my fellow Americans if I were to prostitute as a professional flagwaver and avow that I am living in a political and moral utopia. But for every one unfair rebuff, I’ve had ten openings to seek the equal political and economic opportunities which is the right expected by every American, and here is a point sometimes overlooked by America’s ethnic minorities themselves. I suspect that most White Americans themselves cannot honestly claim that he or she has had the equal treatment which they think they deserve. The obstacles are other than those based on racial or minorities grounds, but barriers nevertheless, against their individual pursuit of happiness. The “black-ball” hits the white as well as yellow and black.

With the small circle of my own largely unfettered pursuit of happiness, I remember ripping off with delight the cadence of “El Capitan” march on a trombone in my country high school band. My bandmaster affectionately called me “China Boy.” And at the state band contest—so vitally important in our young lives—he trusted me with the trombone solo part in Von Suppe’s “Light Cavalry” overture. Chinaman’s Chance! Not on your life. He and 48 other members gave me the American Chance to make good for myself—and for them.

This Chinaman was even given a chance to run his heart out for a 25‑cent medal in the high school track meets. My mother, who came from Canton and never spoke English, never stopped wondering why I exerted myself, half-nakedly, for a medal. Later in 1936, I had enough sense to appreciate it fully when I read about Hitler’s displeasure of Negro [sic] Jesse Owens in doing so well in fair competition with the Aryans at the Olympic Games in Berlin.

College is supposed to be the age and area of class and snob attitudes, distinctions and group inversions sinking firmly in place. But I was given the traditional American chance and right to work my way up—reporter, feature writer, desk editor, managing editor—and finally, election to editor-in-chief of the college daily. Sometimes in exasperation over the trials and tribulations of the newspaper game, I’ve wondered whether I should be grateful—but certainly I am grateful for the American way of life offered me.

They didn’t elect me editor simply because I was an underprivileged Chinese lad. The fact is, it was claimed to be one of the hottest election campaigns ever waged on that campus. They elected me strictly on the American competitive basis.

Out of the artificial world of the campus into the cold realities of life, I struggled at a press bureau, and later on the copydesk of a metropolitan newspaper. Here Eddie, the slot-man, or copydesk boss, was a subject of the King of Sports—and cared more about your knowledge of bangtails and your headline writing abilities than the color of your skin. You wrote a snappy, concise headline that fitted, and it didn’t matter whether your name was Molinari, Abrams, or O’Brien. The men around the copydesk were, in fact, of Italian, Jewish, and Irish extraction. And me, Chinese.