by Russell C. Leong

My father was an itinerant farm worker. He worked in the potato farms, grape crops, and the salmon canneries in Seattle. His life was typical of thousands of Chinese, Japanese and Filipinos in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s.

—Charles Lai Leong, The Eagle and the Dragon

Being from China, my folks did not believe in education for girls. My sisters never went to college. But me, I loved college. I was the rebel in the family. I took a course at a university.

—Mollie Jow Leong, from interview

Throughout China’s history, there have been peoples who have become Chinese as well as Chinese who have become other peoples, both within and outside China’s long and movable borders. Never, however, have the numbers of Chinese ready to become other peoples been so great as during the 20th century.

—Wang Gungwu in Lynn Pan’s The Encyclopedia of the Chinese Overseas (1998)

My father, Charles Lai Leong, met my mother, Mollie Jow Chun, after World War II when he came back from Shanghai. He returned to the U.S., where he was born and schooled, after a successful stint in General Chennault’s 14th Air Force squadron. “Chas” courted “Mollie,” and they were married at the chapel of Stanford University, where Dad was educated. A year later, or so, I was born in 1950, then my younger brother Eric, in 1953. (Dad had told us we could have easily have been born in Shanghai, where a number of Chinese Americans decided to stay to build a New China, or even in Singapore, where the CIA had asked him to utilize his skills as a journalist to help in its South Asia activities.)

So, my brother and I ended up being raised and running the streets of San Francisco Chinatown in the 1950s, trading baseball cards, going to segregated English primary schools and also Chinese language schools run by the Kuomintang Nationalist Party at that time. My memory of Chinese school consists of thin bamboo rods used to strike our palms when punished, and the history of modern China, in our textbooks, ending with a photo of Dr. Sun Yat-sen and a map of the provinces of China. Chinese history, for all ideological intents, ended in 1949. Only in the 1960s, with the strike for Ethnic Studies, Civil Rights Movement, the decolonization of African countries, the naïve embrace of the People’s Republic of China, and my education at National Taiwan University did I garner a more complicated view of myself, my family, and of being a true Chinese American—part of the cohort of what the historian Wang Gungwu calls “Chinese who have become other peoples.”3

No, not White or Black, but Asian American, a discordant, contradictory, creative, and conscious bundle of identities created by history and birth, but most of all, by the choices that my grandparents (agricultural workers and small restaurant owners), my parents (second generation), and my brother and I (third generation) had taken in life. For each generation, leaving and/or returning to China for economic, political, or educational reasons were a part of these choices. To leave the Pearl River Delta region of Guangdong (Zhongshan for my maternal grandparents; Xinhui for my paternal grandparents)… To settle in America (Isleton and Reno for the former; Watsonville, in California’s Pajaro Valley, for the latter)… For my mom, she was the lone sister out of four to refuse an arranged marriage, who went to U.C. Berkeley to study Mandarin with the original intention of joining the WACs and going to China… She refused to marry on account of prospective mothers-in-law pinching her arm to see if she would be good material for producing babies, as she told me. For my dad, from picking lettuce and working in an apple dryer in a small agricultural town, he worked his way to becoming the first Chinese editor of a major college daily (The Spartan Daily, at San Jose State College in the 1930s), and then onto Stanford to obtain his M.A. in Journalism. During WWII, Dad joined the famed Flying Tigers, flying over the Himalayas, to join General Claire L. Chennault in southwest China.

From the Leong Family collection

My father, in his autobiography, The Eagle and the Dragon, wrote of his wartime experience. After the war, Dad remained in Shanghai to work as a field correspondent for UNRRA—United Nations Rehabilitation and Relief Administration, travelling throughout China, and even Taiwan, to cover relief efforts. Anyway, just before the last planes had lifted off the gray tarmac to leave Shanghai, Dad ended back in Chinatown, San Francisco, where he continued working for the Chinese Press, which he had co-founded with William Hoy in 1940. The war had interrupted his journalistic ambitions in the U.S., but he touted the paper as an English-language paper by and for Chinese Americans. Penning this note, I’m sitting on his old wooden swivel chair, polished by time, on which he had written many news columns and essays for the Chinese Press in the 1940s and 1950s, and even during his stints at the San Francisco Chronicle, the Young China Daily, East-West, United Press, etc., during his extensive and pioneering journalistic career.4 On my desk is a vintage Sanford’s Library Paste Utopian glass jar (rescued from my dad’s Chinatown office) which was used for newspaper mock-ups—in a world of journalism without computers, where stories and photos were typed, cut, and pasted by hand.

New Futures Across Old Divides

In brief, this is the outline of the world—more than half-a-century ago—in which my brother and I grew up, during the McCarthy Era, and before the 1965 Immigration Act or the Civil Rights Movement. Chinatown, San Francisco, was a village, “Dai Fow” was not a ghetto, and as a youth, the other “America” was glimpsed through the dark tunnel that I needed to go through to reach downtown: an electronic street car would then transport me to Lowell High School, on the far western edge of the city. My father’s autobiographical Eagle and the Dragon, reprinted here, and an interview which I did with my mother on her 75th year, together with other essays and family photos, provide more detail on one Chinese American family. I don’t consider ourselves unusual because it was just our family.

Yet, I realize that we, like generations of other Chinese who had left China in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries for the Philippines, Indonesia, Burma, India, Malaysia, Singapore, Japan, Korea, Hawaii, or as indentured laborers for North, Central, and Latin America, were, and are, collectively part of what it takes to create “other peoples”: neither defined wholly by China, nor by the country we had chosen, or chanced, to settle.

Neither a hyphenated, nor a hybrid entity, we have created cultures, languages, politics, economies, identities, which have served us well, yet also resulted in discrimination, violence, and for some, even expulsion. Each generation, therefore, and I am thinking of this 2lst century and beyond, constitute “other peoples” in the making, with yet infinite possibilities to thrive, to learn, and to create.

As I write, I’m challenged, like so many others, by the global COVID-19 pandemic, xenophobia, uneasy and treacherous U.S.-China relations, the dismemberment of Hong Kong under a new security law, Black Lives Matter, and new, hopeful political alignments around the world. Ironically, I feel that there is no better time to be Chinese American, because we can be a radical part of change toward social justice.

Yet, precisely because we cannot be neatly cordoned within the nationalistic borders of “China” or “America” with their own peculiar ethnocentric, ideological, or chauvinistic biases, we can create a vivid third identity across simmering East-West divides.

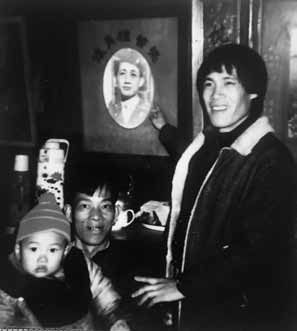

Russell sees his father’s military photo

on the wall of relatives’ home, 1984.

Photo courtesy of Russell Leong.

A Village through the Mist

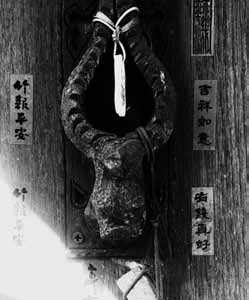

In tribute to my parents, and grandparents from Zhongshan and Xinhui, I include here passages from “Aerogrammes” a poem from The Country of Dreams and Dust (West End Press, 1993) which received the PEN Josephine Miles Poetry Award. “Aerogrammes” is about my first trip to China, in 1984, to my father’s village, Cha Hang (Chakeng) 茶坑, Xinhui County, the birthplace of late Qing dynasty reformer, statesman and scholar, Liang Qichao.5 (For thirty years, I’ve hung a small chunk of stone, wrapped in cord, from my front doorway, picked up from the rubble around the pagoda-like tower on the green hill above Chakeng village.) Sometimes I can see that hill through the mist, or smell the dried, burnt-orange tangerine peels that Xinhui is famed for.

In the village, graced by an arch and museum memorializing Liang, the relatives take me to a small stone house, where my father’s photo, and his Chinese name 梁普礼, are emblazoned on the picture frame. I join relatives to light incense and offer whiskey to my grandfather on the side of a hill, just like Dad did on his wartime visit to the village. My old uncle remembers pensively when my dad, during WWII, had visited the village. He was the first to ever return from America, Uncle told me. The elders spoke in Xinhui dialect, and the youngsters translated to Putonghua or Cantonese for me to answer. Upon my return to the U.S., blue aerogrammes arrived from my relatives, asking for money to start a business. Instead, I telegrammed money noted with a special request to buy my uncle a thick coat against the damp tropical winters of southern China.

Photo courtesy of Russell Leong.

“Aerogrammes” (Part I)

Par avion, via airmail, hang kung

Only after I returned to L.A. did China collapse in my hand—

Folded, sealed, glued and stamped westward.

I did not ask to be followed.

But someone’s village childhood,

Spent among the palmettos, pigs and orange groves

Of the Pearl River Delta

Caught up with me generations later.

Now, five blue- and red-striped

Aerogrammes corner my desk, airmail-stickered

In French, English, and Chinese

Addressing my journey to Xinhui.

In Canton City

The words of the woman driver dart past my ears:

“Don’t get your relatives Marlboros—

Why spoil them!

Local cigarettes are good enough—

And good for the economy!”

“How ‘bout a chicken?” I ask.

“Wait and see—you may not like your country cousins!”

I slip four cartons—

Two American brand and two Chinese—

Into my bag anyway.

On his visit to the Chakeng village,

Harvest is over by December.

Along the pockmarked roads,

Men knee-deep in winter mud

Fill ditches, repair dikes.

Traffic holds us up –

I give her a piece of my mind.

“When I was young in America,

we believed in Mao, revolution, socialism.

Now China travels the capitalist road.

What should we believe?”

She laughs.

“We never had ships

searching for spices or gold,

or far-flung empires built on slaves.

But a little capitalism today

Is a good tonic to cure feudal ideas!”

She sips a Coca-Cola

I buy at the roadside stand.

Traffic unsnarls—

We reach Xinhui

Where she leaves me

To a local fellow from the village clan.

In the clan hall,

Around a wooden table,

The elders tug at stray whisker in thought.

From my pocket, I fetch a black and white photo

Of my father from World War II.

“Does anyone here remember this man?”

They pick at the image

Like a scab off memory,

Narrow their vision

Down to the eye,

Recap their stories

Down to the tooth.

No, no; yes, yes.

Forward and backward

They lead me through alleyways

Smelling of fish and oranges

To a small house.

I open the door.

My father stares down

From a wartime portrait on the wall.

I cannot deny the relation

When all the children in the room

Suddenly, chime “Uncle……”

______________________

3 National Taiwan University 國立臺灣大學.

4 Charles L. Leong Papers, 1932–1972 are at The University of California Ethnic Studies Libraries. AAS ARC 2000/47. http://www.oac.cdlib.org/search?style=oac4;idT=UCb134573638.

5 Liang Qichao (1873–1923) was born in Jia Heng Village 嘉亨里 of Chakeng 茶坑村 of Xinhui 新会.