As Chinese Americans were recruited as cheap labor to break union lines, anti-Chinese sentiment was especially common during times of economic depression eg in the 1870s and 1890s. In the “Driving Out” period, there are documented anti-Chinese fires and murders in Yreka (1871), Weaverville (1874), Rocklin near Loomis (1876), Chico (1877), San Francisco (1877), and San Jose (1887). Other expulsions were in Tacoma (Washington), Arroyo Grande, Marysville, Merced, Nicolaus, Pasadena, Redding, Red Bluff, Riverside, Truckee, Tulare, and elsewhere. Here is a look at a few of these anti-Asian hate incidents.

1871 Los Angeles, California

The 1870 census records the names of 172 Chinese—or 3%—of the Los Angeles community of 5,728. These Chinese were deeply embedded in the local economy working as cooks, entrepreneurs, blue-collar workers, and 37 working as domestic live-ins. About half of the Chinese Americans lived in adobe structures along the unpaved Calle de los Negros—now renamed Los Angeles Street. There were business rivalries, and on 24 October 1871, gunfire erupted between the Hong Chow Company and Nin Yung Company, both factions of the Sze Yup Association. Ah Choy was shot in the neck. The fighting was over the kidnapping of Yut Ho2, wife of one of the faction leaders.

The shooting caused one of Los Angeles six officers, Jesus Bilderrain, to investigate. Bilderrain was wounded. The owner of the popular Blue Wing saloon, Robert Thompson, followed Bilderrain and was killed in the crossfire. It was the killing of Thompson that triggered an “orgy of violence”3 by a mob of over 500 bent on revenge, randomly finding and killing Chinese American men and boys.

The next morning, seventeen bodies were laid out in the jail yard, grim evidence of the horrific events of the previous night. The eighteenth victim, the first man hanged4, had been buried the night before. Ten percent of the Chinese population had been killed. One of the Chinese caught up in the mob violence was the respected Dr. Gene Tong.5 In fact, of the killed, only one is thought to have participated in the original gunfight.

Though a grand jury returned 25 indictments for the murder of the Chinese, only ten men stood trial. Eight rioters were convicted on manslaughter charges, but the charges were overturned on a legal technicality, and the defendants were never retried.

The tragedy was quickly forgotten; the local newspapers made no mention of it in the year end recap of major events of the year. The unfortunate truth is that little changed in Los Angeles as a result of the massacre on 24 October 1871. In fact, anti-Chinese sentiment increased in the following years. The Anti-Coolie club was formed in 1876, counting many prominent citizens among its members, and the newspapers resumed their editorial attacks against the Chinese.6

1871 Los Angeles Victims7

- Ah Wing

- Dr. Chee Long “Gene” Tong, physician

- Chang Wan

- Leong Quai, laundryman

- Ah Long, cigar maker

- Wan Foo, cook

- Tong Won, cook and musician

- Ah Loo

- Day Kee, cook

- Ah Waa, cook

- Ho Hing, cook

- Lo Hey, cook

- Ah Won, cook

- Wing Chee, cook

- Wong Chin, storekeeper

- Johnny Burrow, laundryman

- Ah Cut, liquor maker

- Wa Sin Quai

Now, Los Angeles Street.

1876 Antioch, California

Antioch is between Oakland and Stockton. On 29 April 1876, a White doctor alleged some Chinese had venereal disease, and a mob of about four dozen gathered. They insisted that all Chinese leave town by 3 pm. The small Chinatown included shops on First and Second Streets near I Street with a flotilla of houseboats on the San Joaquin River. Because of concern that the Chinese might return, after church services the next day, the Chinatown was burned to the ground. As the community had an earlier “Sundown” ordinance that restricted Chinese movement, the Chinese pioneers around 1851 had built a series of tunnels from their work places to this Chinatown. The tunnels would be used during Prohibition and re‑found during construction work.

In May of 2021, Antioch became the first city to apologize for its past action. The Resolution was passed by all five on the City Council. The mayor, Lamar Thorpe, himself an African American raised by Mexicans in East LA, said in part, “Today, we in the City of Antioch, take a dose of humility by acknowledging our troubled past and seeking forgiveness.”8 In September of 2021, the City of San Jose followed Antioch’s example and apologized for the 1887 fire in that city’s Chinatown which displaced 1400. The City resolution read in part, “An apology for grievous injustices cannot erase the past, but admission of the historic wrongdoings committed can aid us in solving the critical problems of racial discrimination facing America today.”9

1885 Rock Springs, Wyoming

On 2 September 1885 was the most horrendous race riot against Chinese Americans. In Rock Springs, Wyoming, 150 White miners working for the Union Pacific coal mine attacked their Chinese coworkers, mortally burning and mutilating 28 and wounding 15. As the work was most important, U.S. troops escorted the surviving Chinese back the week after. Eventually, Union Pacific fired 45 of the White miners for their participation in the massacre, but no legal action was taken.10

1885 Rock Springs, Wyoming Victims11

Bodies found mutilated and shot:

- Leo Sun Tsung, 51

- Leo Kow Boot, 24

- Yii See Yen, 36

- Leo Dye Bah, 56

Bodies found burned:

- Choo Bah Quot, 23

- Sia Bun Ning, 37

- Leo Lung Hong, 45

- Leo Chih Ming, 49

- Liang Tsun Bong, 42

- Hsu Ah Cheong, 32

- Lor Han Lung, 32

- Hoo Ah Nii, 43

- Leo Tse Wing, 39

Bone fragments or no bodies found:

- Leo Jew Foo, 35

- Leo Tim Kwong, 31

- Hung Qwan Chuen, 42

- Tom He Yew, 34

- Mar Tse Choy

- Leo Lung Siang

- Yip Ah Marn

- Leo Lung Hon

- Leo Lung Hor

- Leo Ah Tsun

- Leang Ding

- Leo Hoy Yat

- Yuen Chin Sing

- Hsu Ah Tseng

- Chun Quan Sin

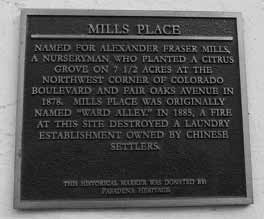

Plaque near today’s Cheesecake Factory

on Fair Oaks Avenue in Old Town Pasadena.

1885 Pasadena, California

On 6 November 1885, a mob of 100 harassed the Chinese residents in Pasadena. A decade earlier, Yuen Kee established the first known Asian American business, a laundry, on South Orange Grove Blvd. In 1883, he moved this business to Fair Oaks Avenue near Mills Place and a few other Chinese businesses and residents congregated in the proximity. On the evening of that Friday, a group grew outside the laundry muttering about Chinese stealing jobs. Inside the laundry, nine or ten Chinese Americans worked to the light of a kerosene lamp. Someone threw a stone through the laundry’s glass window, and a fire ensued. A White mob surrounded the building where Chinese workers hid. By the next day, Pasadena drafted the city’s first racial zoning ordinance and segregated the Chinese south of California Blvd.12

1886 Hells Canyon, Oregon

In May, along Snake River, a group of Whites robbed, murdered, and mutilated about 34 Chinese gold miners. The miners were working for Sam Yup Company. Some of the bodies were found down river after months. Most of the Chinese names are not known but it is said they are from the “Punju” region—probably Panyu 番禺区. Three of the seven White horse thieves were brought to trial in 1888 and found “not guilty” quickly. The other gang members probably left the area.

1886 Hells Canyon, Oregon Known Victims13

- Chea Po

- Chea Sun

- Chea Yow

- Chea Shun

- Chea Cheong

- Chea Ling

- Chea Chow

- Chea Lin Chung

- Kong Mun Kow

- Kong Ngan

- Ah Yow

1906 Santa Ana, California

In 1877 and 1890s, there are documented cases of harassment of Chinese in Anaheim and Santa Ana led by members of the Anti-Coolie League and Ku Klux Klan. In 1906, there was a claim that a Chinese man named Wong Who Ye had leprosy, and this was justification to burn down the whole Chinatown of “junky redwood shacks” on Third Street between Main and Bush. On 25 May 1906, a thousand residents lined the streets and watched the deliberate torching of this Chinatown. In the 1910 census, there was only one Chinese person reported in Santa Ana, and 83 in all of Orange County. In the years to come, city boosters were proud to claim that their community had “no Chinatown.”14

1982 Detroit, Michigan

On 19 June 1982, 27-year-old Vincent Chin was at a bar to celebrate his upcoming nuptials. He got into a shouting match with Ronald Ebens and Michael Nitz, two unemployed autoworkers. The American automobile industry was unjustly blaming their economic problems on the Japan-based manufacturers during an oil crisis, and Ebens and Nitz assumed Chin looked Japanese. In the parking lot, Ebens and Nitz procured a baseball bat from the back of their car, and Chin ran. After a 20-minute chase, Ebens and Nitz found and beat Chin to death.

The case did not cause mainstream exasperation until Judge Charles Kauffman at the sentencing claimed that Ebens and Nitz were “good men” and fined each $3000 and 3 years of probation. Kauffman said, “These weren’t the kind of men you send to jail… You don’t make the punishment fit the crime; you make the punishment fit the criminal.” The Vincent Chin case instigated a national civil rights engagement.

Judge Kauffman retired from the Third Circuit Court of Michigan in 1992 and died in 2004. In 1987, a civil suit was filed against Ebens and Nitz.

Nitz paid $50,000 over ten years. In 2021, Ebens is still living quietly in Henderson, Nevada. With the move, Ebens avoided paying his $1.5 million wrongful death judgment—now grown to over $8 million with interests.

2021 Atlanta, Georgia

In March of 2020, the nation went into quarantine after failure to contain the coronavirus. In May of 2020, George Floyd was killed by a Minneapolis police officer for allegedly using a $20 counterfeit bill. Former officer, Derek Chauvin, choked Floyd for over eight minutes—while the scene was being captured on several cell cameras. At the same time, anti-Asian violence was noticeably increasing.

It was in March of 2021 that six Asian American women and two others were shot in 3 separate spas by Robert Aaron Long in the Atlanta area.

2021 Atlanta, Georgia Victims15

Identified by Fulton County Medical Examiner’s Office:

- Hyun Jung Grant, 51, gunshot wound to head, worked at Gold Spa

- Suncha Kim, 69, gunshot wound to chest, worked at Gold Spa

- Soon Chung Park, 74, gunshot wound to head, worked at Gold Spa

- Yong Ae Yue, 63, gunshot wound to head, worked at Aromatherapy Spa

Identified by the Cherokee County Sheriff’s Office:

- Daoyou Feng, 44, worked at Young’s Asian Massage

- Paul Andre Michels, 54

- Xiaojie Tan, 49, owner of Young’s Asian Massage

- Delaina Ashley Yaun Gonzalez, 33

_______________________

2 Or “Ya Hit” according to Cecilia Rasmussen in “A Forgotten Hero from a Night of Disgrace,” Los Angeles Times, 16 May 1999. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1999-may-16-me-37851-story.html.

3 John Johnson, Jr, “How Los Angeles Covered Up the Massacre of 17 Chinese” in LA Weekly, 10 March 2011. https://www.laweekly.com/how-los-angeles-covered-up-themassacre-of-17-chinese/.

4 Along with half a dozen other Chinese at Tomlinson Corral on Temple and New High Street/Spring Street.

5 Elsewhere listed as Chee Long Tong and Chien Lee Tong.

6 Kelly Wallace, “Forgotten Los Angeles History: the Chinese Massacre of 1871,” Los Angeles Public Library, 19 May 2017. https://www.lapl.org/collections-resources/blogs/lapl/chinese-massacre-1871.

7 Scott Zesch, “Chinese Los Angeles in 1870–1871: The Makings of a Massacre”, Southern California Quarterly, 90 (Summer 2008), 109–158. Accessed from “Chinese Massacre of 1871,” Wikipedia, 7 July 2021.

8 From “Six O’clock News” of 18 June 2021, KPIX CBS SF Bay Area.

9 Associated Press. “San Jose Apologizes for Chinatown Destruction in 1887,” Los Angeles Times, 28 September 2021. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-09-28/sanjose-apologizes-for-1887-chinatown-destruction.

10 History.com Editors. “Chinese are Massacred in Wyoming Territory,” History.com, 16 November 2009. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/whites-massacre-chinese-in-wyoming-territory.

11 History Matters: A U.S. Survey Course on the Web, “To This We Dissented: The Rock Springs Riot,” George Mason University. http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5043/. Also in “Rock Springs Massacre,” Wikipedia. Accessed 7 July 2021.

12 Matt Hormann. “Night of Terror,” Pasadena Weekly, 5 November 2015. https://pasadenaweekly.com/night-of-terror/. Accessed 7 July 2021.

13 R. Gregory Nokes, “A Most Daring Outrage, Murders at Chinese Massacre Cove, 1887,” Oregonian Historical Quarterly, Fall 2006, Vol. 107, Number 3, p. 331. https://www.ohs.org/research-and-library/oregon-historical-quarterly/upload/Nokes_A-Most-Daring-Outrage_OHQ-Fall-2006_107_3.pdf.

14 Patricia Lin. “Perspectives on the Chinese in Nineteenth-Century Orange County,” in Bridging the Centuries (Chinese Historical Society of Southern California, 2001) pp. 73–79. Also, Gustavo Arrellano’s “Santa Ana Deliberately Burned Down Its Chinatown in 1906—And Let A Man Die to Do It” in OC Weekly, posted on 30 December 2014 at <https://www.ocweekly.com/santa-ana-deliberately-burned-down-its-chinatown-in-1906-and-let-a-man-die-to-do-it-6446664/>.

15 Ryan W. Miller, Trevor Hughes, Romina Ruiz-Goiriena, Jorge L. Ortizm and Jordan Culver. “Hard workers, dedicated mothers, striving immigrants: These are the 8 people killed in the Atlanta area spa shootings,” USA Today, 19 March 2021. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2021/03/19/who-are-atlanta-shootingspa-