By Raymond Douglas Chong 张伟明

Editor’s note: Raymond Chong, a civil engineer in Texas, is descendant of the Zhang/Jung family associated with the Far East Cafe in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo. He contributes to AsAmNews. This article complements his previous article on Santa Barbara’s Yee Clan in Gum Saan Journal 2014. (See gumsaanjournal.com.) Chong’s consistent efforts to reclaim Chinese American history remind us that through history, we find our strength.

Across a vast America, dozens of Chinatowns dotted the American cityscape. Some of these ethnic enclaves have sadly faded in people’s memories. Only archival stories, vintage photos, and unique films remain inside dusty bins. At Santa Barbara, on the Gold Coast of California, a lost Chinatown is remembered.

Sojourn from Cathay

in front of his ancestral home

in Long Gang Li (Dragon Hill Village), Kaiping, 2007.

Photo courtesy of Raymond Chong.

During the 1848 to 1855 California Gold Rush, the early sojourners, peasants from Guangdong, arrived at the Port of San Francisco. They sought their fortune amid the rich gold fields beyond Sacramento. Some were from the districts of Taishan, Kaiping, Xinhui and Enping; others were from the Sanyi region. They panned for gold along the lucrative rivers. After the gold resource was exhausted, the Chinese drifted through the hinterland of California for hard work on the mines in the foothills, farms in the valleys, and fisheries along the coast.

From 1868 to 1869, Chinese workers built the Santa Ynez Turnpike Road at San Marcos Pass, now called the Stagecoach Road on Highway 154. They built the Southern Pacific Railroad Coast Line between Saugus junction and Goleta in 1887. The commerce at Santa Barbara was driven by cattle and sheep ranches, vegetable farms, fruit orchards, and abalone fisheries. Chinese labored in the vegetable gardens and fruit orchards for the Hollister, Stow, Cooper, and Storke families. In resort hotels, including the landmark Arlington Hotel, and private homes, they served as servants, housekeepers, and cooks. Still others worked as laundrymen. From 1864 to 1913, Chinese were plying the sea near Channel Islands for abalone; the shell was prized for ornamentation and jewelry and the meat was salted and dried. In the 1890s, six sampans operated from the port of Santa Barbara. California state laws would force the Chinese out of this industry.

Old Chinatown at Santa Barbara

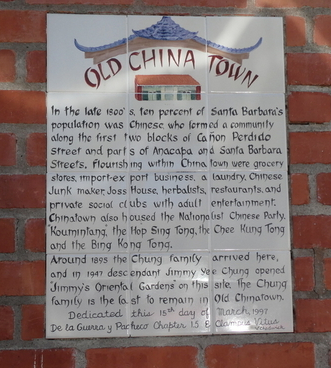

Today, a glazed tile plaque is outside the iconic Jimmy’s Oriental Gardens Restaurant. Here, an Old Chinatown, a ghetto, had emerged as a cultural and residential hub, among the adobe, wooden and brick buildings on 00 block of East Canon Perdido Street, between State Street and Anacapa Street, with storefront businesses and above ground apartments. As they become settled, Chinese entrepreneurs operated stores, restaurants, and laundries. Ah Lim opened a cookhouse on State Street to feed the hungry workers as early as 1862.

Old Chinatown consisted of a temple, tong halls, grocery stores, rooming houses, barber shops, and labor contracting offices. Gambling halls and opium dens were at backrooms or upper floors, places for the men to escape the tedium of a cruel bachelor society. Farmhands lived outside Old Chinatown.

In the 1880 census, total Chinese population was 79, with 67 men and 12 women. The men were mostly laborers (46), cooks and waiters (10), laundrymen and washermen (4), and servants (3). A map by the customs inspector in 1894 showed 17 general merchandise or grocery stores, three apartments, one temple, one tong, two barbershops, one restaurant, one contactor, six opium dens, and one gambling parlor. Business partners were employees and clan cousins. Sing Chung Company, Sing Hop Company, Sun Lung Company were major abalone dealers. Immigration and Naturalization Service monitored Chinese merchant partnerships. They included Hing Lee & Co; Taue Hing & Co; Sue Kee; Tue Lee; You Kee Co; Wing Hing & Co; Hong Yee Kee & Co; Kung Sing; Gee Song Hop & Co; Sue Gee; San Lung & Co; Wah Lee & Co; Tuck Lee & Co; Kee You; Fung Sing Co; Ung Sam Wah & Co; Kee Fung & Co; and High Lung Laundry—located in an adobe building at 15 Carrillo Street. The joss house, at 25 East Canon Perdido Street, had a gold-leafed and hand carved shrine from China.

A reporter for the Santa Barbara Morning Press observed on 4 October 1898:

The Chinese celebration in dedication of their new altar went off with a Fourth-of-July bang yesterday. During the noon hour they exploded $50 worth of firecrackers in front of the joss house, while within the devout Mongolians bowed themselves to the floor, until their heads cracked. Candles and incense were burning, and their offerings included all description of roast meat and fowl, and all the while the aged priest in his flowing robes was in respectful attendance. The altar is a gift to the joss house from the boys of the Sin Lung Company (sic), whose headquarters are in the store next to the opera house; the boys are nearly all engaged in abalone fishing. The altar, including freight and duty, cost $1,000.

The Chinese population in Santa Barbara peaked in 1910 with a census count of 262 people. The 1913 International Chinese Business Directory enumerated 1 restaurant, 1 society, 8 general merchandise stores, 15 groceries, 1 laundry, 2 cigars store, 1 abalone dealer, and 1 chop suey house.

In the 1920 federal census, the total Chinese population was 171, with 156 men and 15 women. The men were mostly cooks and waiters (32), laundrymen and washermen (24), and merchants (24). On 29 June 1925, a strong earthquake struck Santa Barbara, and the Old Chinatown was damaged. Prominent White property owners expelled the Chinese by condemning its buildings. They demolished the rest of Old Chinatown to create a “cohesive Spanish Colonial Revival style” for a growing downtown.

Source: https://calisphere.org/item/97d91d5916740c6ff55a07005b5e3df6/.

New Chinatown at Santa Barbara

Elmer Whittaker, realtor and entrepreneur, built a New Chinatown with funding from three Chinese merchants in the late 1920s. Whittaker built a complex of stucco Spanish Colonial Revival style two-story buildings on the 100 block of East Canon Perdido Street between Anacapa Street and the 800 block of Santa Barbara Street. From 1932 to 1955, a Guomindang (Nationalist Chinese Party) office was at 834 Santa Barbara Street.

Ella Yee Quan32, a Santa Barbara native, recalled the life in New Chinatown during the 1930s to 1940s. Storefront businesses were on the ground floor, while residences were on the second floor. The first building had 12 units on East Canon Perdido Street and the second building had 8 units on Santa Barbara Street. The streets were dotted with the Hop Sing Tong Association, Bing Kong Tong Association, grocery stores, restaurants, laundry, herbal store, general merchandise stores, and cigar stores. Children attended Lincoln Elementary School, Santa Barbara Junior High School, and Santa Barbara High School. They learned Sze Yup dialect at Chinese language school. They played at the Chinese clubhouse. They were involved with the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts. They did odd jobs. On Sunday, they attended the Chinese mission at the First Presbyterian Church.

In the 1940 federal census, total Chinese population was 186, with 121 men and 65 women. The men were enumerated as washermen (24), cooks and waiters (9), and merchants (7). During the Rice Bowl Festival in 1941, the Chinese community raised aid for United Chinese Relief. With the Great Depression and World War II, the hub of businesses slowly faded away as the Chinese population dwindled.

In 1947, Whittaker built the last piece of New Chinatown, Jimmy’s Oriental Gardens Restaurant, for James “Jimmy” Yee Chung. Roy W. Cheesman, architect, designed the landmark building, while Whittaker & Snook was the contractor. The one-story restaurant had a brick facade, tiled and gabled roof with Chinese decor. The two-story stucco residence with tile roof was in the back. In accordance with Chinese tradition, Jimmy held a grand opening for the Chinese community of Santa Barbara. It was a memorable gala event. This landmark restaurant was well-known for its Cantonese cuisine, better known as “chop suey”, as well as gigantic egg rolls and powerful drinks like the Mai Tai cocktail. Patrons danced to a live band.

In the June 1949 edition of the Santa Barbara Telephone Directory, only three businesses remained in Santa Barbara Chinatown. They were Hing Yuen Grocery, 138 East Canon Perdido; Yat Sun Laundry, 136 East Canon Perdido; and Jimmy’s Oriental Gardens Restaurant, 126 East Canon Perdido. Chinese businesses beyond Santa Barbara Chinatown included:

- Sun Tong Laundry 26 East Ortega

- Hong Huy Bow, herbalist, 135 East De La Guerra

- Kong Company, 1108 State

- Kong’s Yu Ting, El Paseo Studio C

- Fong Brothers Market and Liquor Store, 902 Cacique

- Lee’s Grocery Store & Market, 1334 Cacique

- Nanking Garden Cafe, 718 1/2 State

- Shanghai Low Caf., 20 East Cota

A Memory of New Santa Barbara Chinatown

The Yee Family was prominent in Santa Barbara.33 Born in 1931, Mary Yee Young grew up in New Chinatown. Her father was Henry Yee, and her mother’s name may have been Chin Quen Lin. Mary attended Lincoln Elementary School, Santa Barbara Junior High School and Santa Barbara High School.

I remember growing up in Chinatown, a half block on East Canon Perdido Street and a half block on Santa Barbara Street. Mom died soon after I was born. I had two older sisters, Ella and Jessie, and one older brother, Joe.

We crowded on the 2nd floor apartment at 829 . Santa Barbara Street. It had two bedrooms, a bathroom, and a living room. But no hot water nor heater. The kitchen had an ice box and gas stove. I baked chocolate chip cookies for my “uncles.”

In the community backyard, the men would always smoke there. We had a chicken coop for chickens to lay eggs. Other folks raised pigeons and rabbits. We also had a garden to grow Chinese vegetables.

Yee Wah Yee, my grandpa, was an herbalist. He had a general merchandise store, Sam Lee Woo, at 829 Santa Barbara Street. Later, he operated Modern Cafe at 136 East Canon Street. Many Filipino farmworkers ate at the restaurant. Henry Yee, my father, was a casual laborer.

We lived in poverty. I wore hand-me-down clothes from my older sisters. We had no money to buy toys and games. Instead, we played with old playing cards. I learned to play the violin. But I did not attend Chinese language school.

I worked odd jobs after school, during weekends and summers. I packed lemons. I babysat kids. I sold photographer coupons and Christmas cards. I worked at the children’s ward at St. Francis Hospital.

I had many friends, but Dad would not let me date boys until I turned 18 years old. I missed junior prom and senior prom during high school. I occasionally socialized at Hing Yuen Company, a grocery store, at the corner on 138 East Canon Perdido Street. I was involved with the Girl Scouts.

Elmer Whittaker, the landlord, collected the monthly rent. He was nicely dressed and talked well. At his house across the street, in Chinese dress, I served dishes at the couple’s parties. Jimmy’s Oriental Gardens Restaurant at 124 East Perdido Street was next door. Jimmy Yee Chung had a two-story house in the back lot.

When I was 21 years old, I left Santa Barbara Chinatown for a better opportunity in Los Angeles.

______________________

32 Dearest Ella (1926–2004), granddaughter of Y.W. Yee of Santa Barbara, was involved in so many agencies and organizations associated with Asian Americans. She served as president of CHSSC and co-editor of Gum Saan Journal. Her article about Santa Barbara’s Chinatown was first published in Gum Saan Journal in November of 1982, which was reprinted in Bridging the Centuries (CHSSC, 2001).

33 For more stories, see Raymond Chong’s article in Gum Saan Journal 2014 available at gumsaanjournal.com.