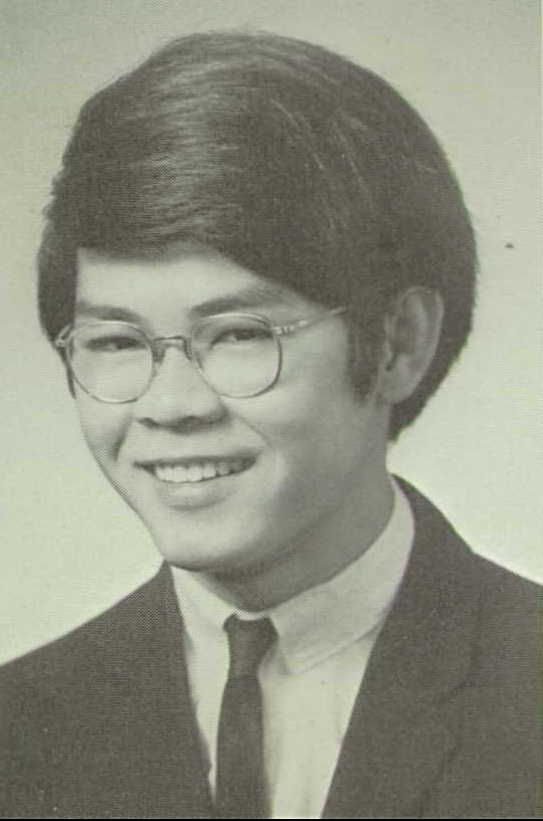

Editor’s Note: Young Gee was born in 1952 in Oroville, California. He had a 34-year career as an English as a Second Language (ESL) teacher at UCLA, University of Guadalajara Mexico, CSU Northridge, CSU Los Angeles, SF City College, and Hollywood Adult School. He retired as Associate Professor from Glendale Community College. His husband is filmmaker Arthur Dong, and they are parents to Reed Dong-Gee. This is transcribed from a Zoom interview held on 31 May 2022.

Roots in Oroville[1]

Both my grandfather and father were paper sons from Gee Hung village of Toisan 台山 (Taishan). My father came as my grandfather’s cousin. My grandfather’s paper name was Lee You, and my father’s was Sun Gee (1918-2001). His real name was Gee Lun Fong. My family are actual Gees, so I luckily ended up with my real name. However, it was strange growing up having to call my grandfather “my uncle” when using English. My grandfather pooled his money with another relative – maybe my grandfather’s uncle – in the early 1900s to start a small restaurant in Oroville. Because of the early land restrictions, the restaurant was right next to the Western Pacific railroad tracks – but on the north side. The south side of the tracks had more African Americans. That restaurant still exists. Later on, they bought land and built another restaurant, Tong Fong Low 东方楼, around it. The Chinese restaurant was very successful. It served chop suey, fried rice, sweet and sour pork, etc.

My father went by Fred Gee and came in 1936 at the age of seventeen.[2] He was married before he immigrated, but my mother, May, and my oldest brother, Wing, had to stay behind in China because Sun Gee was an unmarried man. My father served in the U.S. Army during World War II, and he brought over my mother as a war bride. After 52 years as a restauranteur, my father eventually sold the business as none of us wanted to work there. Most of the family went to the Bay Area. The last time all of us were in Oroville was to dedicate a bench in the name of my parents near the Oroville Chinese Temple. We then had a big family dinner at Tong Fong Low.

The restaurant was sold to another Chinese immigrant family in 1995. Tong Fong Low is said to be the oldest continuously running Chinese restaurant in California. I don’t know if that’s actually true.

Source: https://www.tongfonglow.com.

Accessed 6 June 2022..

Our family restaurant was known as Charlie’s Chop Suey as they used to call my grandfather Charlie as in “Charlie Chinaman.” My father was called Charlie, too. When I started working at the restaurant, they called me Little Charlie. I hated that, and I couldn’t wait to get out of that restaurant and Oroville.

My grandmother immigrated in the 1960s. My mother, grandmother, and most of our Chinese workers did not speak English. My grandfather spoke broken English and was proud of being “longtime Californ”.[3] He deserved that pride because he was able to reunite the family in America, develop a successful business, and build a grand house for his son in Oroville. I don’t know much of the Gee family history in China. They sent money to China, but I didn’t know to whom. It was as if they didn’t want us children to know about the past; they wanted us to look to the future. Now that I’ve worked many decades as an ESL teacher, I understand how some immigrants want a separation from the past for their children and for their new life.

I have eight brothers and sisters. My oldest brother was born in China, and the rest of us were born in Oroville. There were 3 boys and 6 girls, and I was the 6th child. I was born in 1952. We were born in clumps in that four of us were born in four years. The only distinct memory from my infancy is of a room of crying babies.

Source: https://www.tongfonglow.com. Accessed 6 June 2022.

Oroville was very small then, about 5000. When the Oroville Dam was completed in 1964-65, Oroville grew, and the restaurant became even more popular as it was the only Chinese restaurant in the area. Our town was a cute little town. We all went to Oroville High School, and in the four years of my high school, there was almost always a Gee in every class level. Until I was about 14, there was only one other Chinese family in Oroville: the Chans. But the father, who was a civil engineer for the city, died, and the family left. After the Chans left, the only other Asian in Oroville was an elderly Chinese man who ran a laundry, of course. I grew up with Caucasian children until busing integration happened.

When my father wanted to buy land to build a house for his growing family, no one would sell to him, but he got a Caucasian friend to buy the land on his behalf. The land was next to a trailer court, an ice factory, and a medical building. My dad built the biggest house in the neighborhood on the lot, and he was proud that our house was one of the first in Oroville to have central air and heat. Our lives revolved around the house, school, and the restaurant. My parents kept us isolated in many ways, and I suppose it was to keep us safe as well as to maintain our Chinese identity.

I remember once going across the street with my sisters to play with our neighbors. We were enjoying ourselves, and we said, “Let’s go to our house to play some more.” The friend said to her mother, “Hey, can I go to the Chinaman’s house?” I was taken aback. “Oh, I’m different from them!” It was my first racial awareness; I wasn’t like them and they saw us as different from them. Unlike Chinese Americans who grew up in San Francisco or Sacramento who had more exposure to racial differences, my brothers and sisters thought we were like all the other children around us, and I even thought that the families around us were just like our family. Of course, they used chopsticks and ate rice at every meal like us. I remember when we invited a neighbor boy to have dinner with us, I was shocked because he put sugar and milk in his rice and ate it with a spoon. Our parents worked long hours at the restaurant, and we were left at home. As a result, our self-identities growing up were influenced by the community around us, movies, and 1950-60s TV. In other words, we really were just like the other kids in the neighborhood in many, many ways.

When my grandparents retired, they would take vacations to San Francisco and would often take me and a couple of my sisters. We would stay at a hotel on Grant Avenue in San Francisco Chinatown and go to Chinese movies and Chinese opera when it was in town. Sometimes, we would go to a Chinatown recreation center and play. It seemed so strange for me to be around so many Chinese kids.

It was a very long process for me to come out as a gay man, but I knew I was attracted to the same sex when puberty hit. I didn’t have the vocabulary, but I knew that I was different from other boys. It was the early 1960s, and I had traditional Chinese parents. Like many gay men of that time, to find information about myself, I went to the local library where I read all these horrible references to homosexuality as deviant behavior. That confused me because I knew I wasn’t deviant or bad in any way, but at that time in history, there was no other place to turn to for information. You couldn’t ask or talk about “the love that dares not speak its name” to anyone outside the family, and I couldn’t confide in my heterosexual family either. As a result, I became deeply closeted.

But things were beginning to change. About the late 1960s, the gay liberation movement started. I was exposed to the counterculture movement and also became more politically aware. I was against the Vietnam War, and the other kids who were outcasts at school were also anti-war. I guess these ideas helped me feel rebellious against all kinds of traditional ways of thinking and living. In April 1971, I went with a group of friends to the San Francisco peace rally.[4] I remember that time distinctly because I saw a lot of gay men in San Francisco. I thought, “Wow, how cool…how liberating…how free!” I had never been around gay men before. Looking back at high school, I am surprised how many of my classmates were gay or lesbian, but we were all closeted and had to have “beards”.[5]

I didn’t see myself as different from my Caucasian friends even though I also identified as Chinese. I never had a problem being Chinese. My problem was being gay, until it wasn’t a problem anymore. Although I thought of myself as essentially not different from Caucasian, most of the Caucasians saw me as exotic and strange, which frustrated me a lot. They would ask me, “Where are you from?”… Oroville… “I mean where are you really from?”… Oroville… Also, they expected me to know everything about Chinese culture and history.

“Wild Young Thing”

All of my siblings identified as heterosexual, and their lives followed what Chinese parents typically expect: attend UCs, become professionals, marry, and have children. Because I was beginning to accept my sexuality, I couldn’t see my life developing in that pattern. I dropped out after one semester at Chico State because I was so mixed-up.[6] I wasn’t ready for academic study because I felt conflicted over my identity and my future. I felt I was a big disappointment to my parents who expected me to marry, have children, and live a heterosexual lifestyle.

I felt rootless a lot after that, and I needed to discover myself as a gay man. I don’t remember how my “gaydar” helped me find them, but I started hanging out with the gay community in Oroville, and they became my family.[7] In every small town, gay men find ways to connect with each other and develop relationships. One of the guys had a mother with an insurance business near our restaurant. She had a back house, and we hung out there. We would socialize, watch TV, read, and have parties. The mother was Mormon, but she was accepting of her son. He was a long-haired hippie who had moved back to Oroville. I guess one could say that I found a group of friends who had dropped out of society in a true countercultural manner of the time. They didn’t have jobs because taxes contributed to the War, shunned traditional culture, and wanted to be free in every way.

At that time, the War in Vietnam was still being fought. I had a high draft number, so I decided to hitchhike to Canada with a friend to see if dodging the draft was an option for me. It wasn’t, so I returned. I went to San Francisco a lot too and began to go to gay bars. That’s where I met my first boyfriend – White, of course. He was tall, with long blond hair, and originally from Texas. For the next couple of years, we lived together.

The two of us – and three gay friends – rented a big rundown Victorian in downtown Oroville next to the railroad tracks. My partner had been in the Army and was terminated for being gay, so he sued the government and won his case. None of us had jobs then. I suppose it would have been impossible in Oroville given that all of us were open and out gay men, and the laws still criminalized homosexuality. I like to think that we didn’t want to be part of a repressive and racist society, but, actually, maybe we were just lazy, too.

After my partner won his lawsuit, he got a cash settlement, and we moved to San Francisco in 1973. I was still unemployed and simply enjoying life one day at a time. San Francisco was in the middle of the Gay Rights Movement and the gay transformation of the Castro district, where thousands of young gay men from all over America were moving to in order to be free. It was an amazing, thrilling, and transformative time in history to be alive and to have participated in. At that time, the Castro was really rundown and decrepit. Of course, this was a low rent area, so we got an apartment at Market and Castro. Two doors down from our apartment, the Communist Party had rented a storefront where they held classes on Marxism! What an unbelievable memory considering how expensive the area is now.

At that time, I wasn’t really in touch with my family because I was living a new life as a young gay man in San Francisco, experiencing everything previously repressed but now released in Gay Liberation. Now that I’m an older man and a parent, I feel horrible about the way I treated my parents back then. When I came out to my parents in the kitchen, my father just stormed out. My mother cried. After that, she kept asking me to marry a woman and have children, so I got really mad at her. My siblings were involved in their own lives raising their families. I remember one of my younger sisters approached me and asked, “Are you the woman?” I don’t remember my response, but I’m sure I answered “no” and left it like that. Straight/heterosexual society seemed so alien, foreign, and hostile to me: like a different world. It didn’t want me, and as a result, I didn’t want to be a part of it.

When my partner and I broke up, I started dating other guys, but the men I tended to meet saw me as someone from China, not America. Most of the White guys didn’t know how to interact with me as an equal, as another American, and they expected certain stereotypes – but I didn’t fit. They wanted passive, subservient, quiet, foreign…. It was disappointing, and I got tired of that. The drawback was that I didn’t have that much sex. However, for me, that was lucky because I did not catch AIDS.

In time, I grew tired of San Francisco, but I didn’t have many choices. I decided to return to Oroville, and I asked my father if I could run the restaurant. I did everything. I learned how things were done and cooked everything on the menu, but my father never let me do the books. He probably didn’t trust me – justifiably. Restaurant life is brutal. The Taishanese called it shigong 死工 (death work). It was 12- and 13-hour shifts. I didn’t last a year; I hated it. I went to the local community college and got enough units to transfer to San Francisco State.

In San Francisco, I thought I needed to meet non-White gay men, so I got more involved in Chinese American things. I would go to Chinatown to take tai chi classes. I started making gay Asian American friends. I met a couple of trans Asians. One was in process of the sex-change, while the other just presented herself as a woman all the time. I admired them because they were Chinese Americans who were brave, proud, and unashamed of who they were. One was from Hawaii, and the other was from San Francisco. We would go to bars together and have fun. Before AIDS, it was a positive time of gay liberation with Harvey Milk on the City Council.[8] The community was growing by leaps and bounds. A guy named George Leung started an Asian American gay group which I joined. We marched in the gay parades and organized dances to raise money, but it was primarily a social organization. Organizations like Gay Asian Pacific Alliance (GAPA) came later in 1988; they are more political. I remember the first Asian I dated was a Filipino. I felt weird about it because it was funny to have someone that looked like me (laughs).

About this time, I started taking lessons for the Chinese harp – yangqin 箜篌 – through the Community Music Center. I took lessons with the famous Betty and Shirley Wong and their Flowing Stream Ensemble, specializing in Chinese folk music. [9] It was there that I met a fellow student, Arthur Dong – who became my husband.[10] This was about 1976. I went on to study the guzheng 古筝with Liu Weishan 劉維姍.[11] Arthur and I both joined the Flowing Stream Ensemble and performed at various places in San Francisco including the Asian Art Museum.

From Community Music Center’s Facebook page.

Arthur and I hit it off really well because we had a lot in common. Although he was born and raised in San Francisco – across the street from the Cable Car Barn, his father was also a paper son who left his wife and firstborn son in Taishan, brought his wife to America as a war bride, and his mother spoke no English. His parents were very accepting of me, and they took me in. Maybe it was because I spoke Chinese? My parents liked Arthur when they finally met him. Maybe it was because he spoke Chinese? As I felt more connected and comfortable in my private life, I started reconnecting more with my family.

Because Arthur and I had left-of-center political beliefs then, we decided to go to China and “help the revolution.” We were among the first Chinese Americans who went into Communist China after Nixon. We were influenced by the Asian American movement which was pro-PRC at that time. I had to borrow money from my parents to go to China, and they gave it to me probably because they wanted me to see what real poverty was like. When we got to China, we told the comrades in Guangzhou that we wanted to teach English, but they wanted us to enroll in a Chinese language school first. After we visited the school, we decided living in China wasn’t for us. China, Guangzhou, and the Chinese people were poor! There was no central heating and no private cars – just to name a few surprises for us. Everyone wore three layers of clothing and rode bicycles. My parents insisted that I visit my uncle in China, and it was an eye-opening experience. My uncle asked me to bring cooking oil and dried fish from Hong Kong because of food shortages in China. We realized we were just dumb young kids. We had no clue to what China was really like then (laughs). When Arthur and I went somewhere, the Chinese people would get off their bikes and stare at us because we were so different. We traveled in China for about two months and went to Beijing, Mongolia, Guilin, and Xinjiang. Throughout our travels, the Communist Party assigned a spy to monitor us. He befriended us in Guangzhou and then he was “accidentally” in the other cities when we arrived. He wanted to accompany us to Xinjiang too, but didn’t. They assigned a new spy for us (laughs). This was during the Gang of Four tension in the late 1970s.

Of course, we could not say we were gay, but men everywhere in China would hold hands and be close. We told everyone we were hao pengyou 好朋友 or good friends. We slept in one bed, and nobody was bothered by that. It seemed all was good as long as you got married and had kids. I think my mother felt like that too: do whatever you want but get married and have kids.

Becoming My Father in Los Angeles

After I graduated from SF State, I wasn’t sure what to do as a career. Arthur’s brother-in-law said that there was a need for ESL teachers, so I tried teaching at the San Francisco YMCA’s Refugee Resettlement Program – and I really loved it. It was a natural for me. When I was young, I always translated for my grandparents and mother, so I think I was meant to teach ESL. Arthur was getting into filmmaking, and he applied to the American Film Institute in Los Angeles. I applied to a UCLA graduate program and got accepted. We moved together to Southern California in 1984.

As youths, Arthur and I both thought we were anti-establishment, but the truth is we both have traditional values. Have I become like my father (laughs)? Family values are deeply imprinted in both of us. Having a family and maintaining family relationships are important. It is weird because my parents did not let us know about their connections with their extended family. They wanted us to separate from the past. We returned to China again with Arthur’s parents, and then with my parents after they retired. In 2018, I organized a trip for my siblings and their families to go to the Gee home village. Before we left for the trip, I asked my oldest brother, who was born in China, if he was emotionally ready. He laughed and said he had forgotten all of his Chinese. However, when we got to the village and the Gee house, his Chinese came back perfectly, and he actually broke down in tears when he went to the room where he used to live 70 years ago. My parents tried to divorce us from China and made us very American, but the roots are still there. We are Chinese Americans.

Arthur and I legally married in 2008 – before the November vote for Proposition 8. It was a political decision for me. I wanted there to be enough gay marriages so that it would be harder politically to strip that right away from LGBT people. Arthur and I also adopted a son. As gay men, it wasn’t even realistic until Governor Gray Davis changed the California adoption laws for same sex couples in 2003. Our son is biologically Korean and Caucasian, but he identifies as Chinese American. We eat Chinese food, do Chinese New Year, burn incense, have an altar…and that’s what he knows. It’s what our families have always done. Isn’t that American? I’m not uncommon, and I still have that odd feeling that everyone else does the same things as me. My hopes for my son are that he contributes to society and has a fulfilling life. That will make me happy.

[1] Oroville is 65 miles north of Sacramento. As early as 1849, Chinese gold miners were in Butte County. Around 1863, early settlers pooled their resources to build the Liet Sheng Kong 列聖宮, Temple of Many Gods, now run by the City of Oroville. In the 1880-90s, there were approximately 10,000 Chinese Americans here. According to the 2020 census, Oroville City had a population of 20,000 of which 67% are non-Hispanic White, 14% are Hispanic, 14% Asian Pacific Islander, 5% African American, and 2% Indigenous.

[2] “Fred Gee was an active member of the community and sponsored many youth activities and local organizations. Well known and widely respected in Oroville, Fred was honored as the Grand Marshall of the 1973 Feather Fiesta Days parade.” From Oroville High School’s Hall of Fame, accessed 7 June 2022: https://www.ouhsd.org/cms/lib/CA02222577/Centricity/Domain/58/Gee%20Family.pdf

[3] “Longtime Californ’” is the title of Drs. Victor and Brett de Bary Nee’s iconic 1986 book that documented the history and contributions of early Chinese American pioneers in the West.

[4] The distance from Oroville to San Francisco is 152 miles. On 24 April 1971, about 150,000 demonstrated against the Vietnam War in San Francisco while a larger crowd assembled in Washington D.C.

[5] “Beard” is slang for people who knowingly or unknowingly are the romantic partner of a person trying to hide homosexuality.

[6] At Oroville High School, Young Gee was a member of California Scholarship Federation and the National Honor Society. Later he would complete his BA at San Francisco State and his graduate degree at UCLA.

[7] “Gaydar” is a colloquialism from the merging of the words “gay” and “radar” that suggests one’s intuitive guess if another person is queer based on nonverbal mannerisms, social behavior, and the like.

[8] Harvey Milk (1930-1978) was the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California. He was a member of San Francisco’s Board of Supervisor for eleven months before he was assassinated along with Mayor George Moscone. Milk was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009.

[9] Betty Ann Wong is a musicologist who specializes in traditional Asian instruments. Born in San Francisco, she holds a B.A in Music from Mills College (1960) and an M.A. in Music from UCSD (1971). With her twin sister, Shirley, Wong established Flowing Stream Ensemble in 1972. She has composed and played music for many venues including movies and theater.

[10] Arthur Dong is an award-winning director. His works include Sewing Woman (1982), Forbidden City, U.S.A. (1989), Coming Out Under Fire (1994), Licensed to Kill (1997), Hollywood Chinese (2007), The Killing Fields of Haing S. Ngor (2015), and many others.

[11] Liu Weishan is a master of the Chinese zither. She studied at the Shenyang Conservatory of Music from 1949, and is based in San Francisco.